A troubled online elementary school likely will continue to operate its learning centers around Colorado despite nine years of low performance, financial problems, and a recommendation that the school be closed.

Even though some of them had harsh words for school administrators, Colorado State Board of Education members on Thursday seemed uninterested in closing HOPE Online’s elementary school. They delayed a final decision, voting instead to ask the school to come back next month with more information about its finances and whether it can partner with a charter to improve student achievement.

HOPE’s elementary has received one of the two lowest ratings from the state for nine years now, despite a state-ordered improvement plan in 2017. On the most recent state tests, only about 13% of its students were able to meet state standards for reading. Fewer than 6% of the students met standards in math. A state review panel recommended closing the school now — something it has only suggested a handful of times.

“After nine years of underperformance, board reconstitution, and work with an external partner, students are not making the needed academic gains in the HOPE’s elementary school learning centers,” the panel’s recommendation stated.

The State Board of Education has struggled with how to regulate online schools like HOPE. Last year, a divided board first allowed the Aurora school district to close HOPE learning centers within its boundaries, then reversed itself and allowed the centers to stay open. Aurora has cited many of the same concerns that the state review panel found.

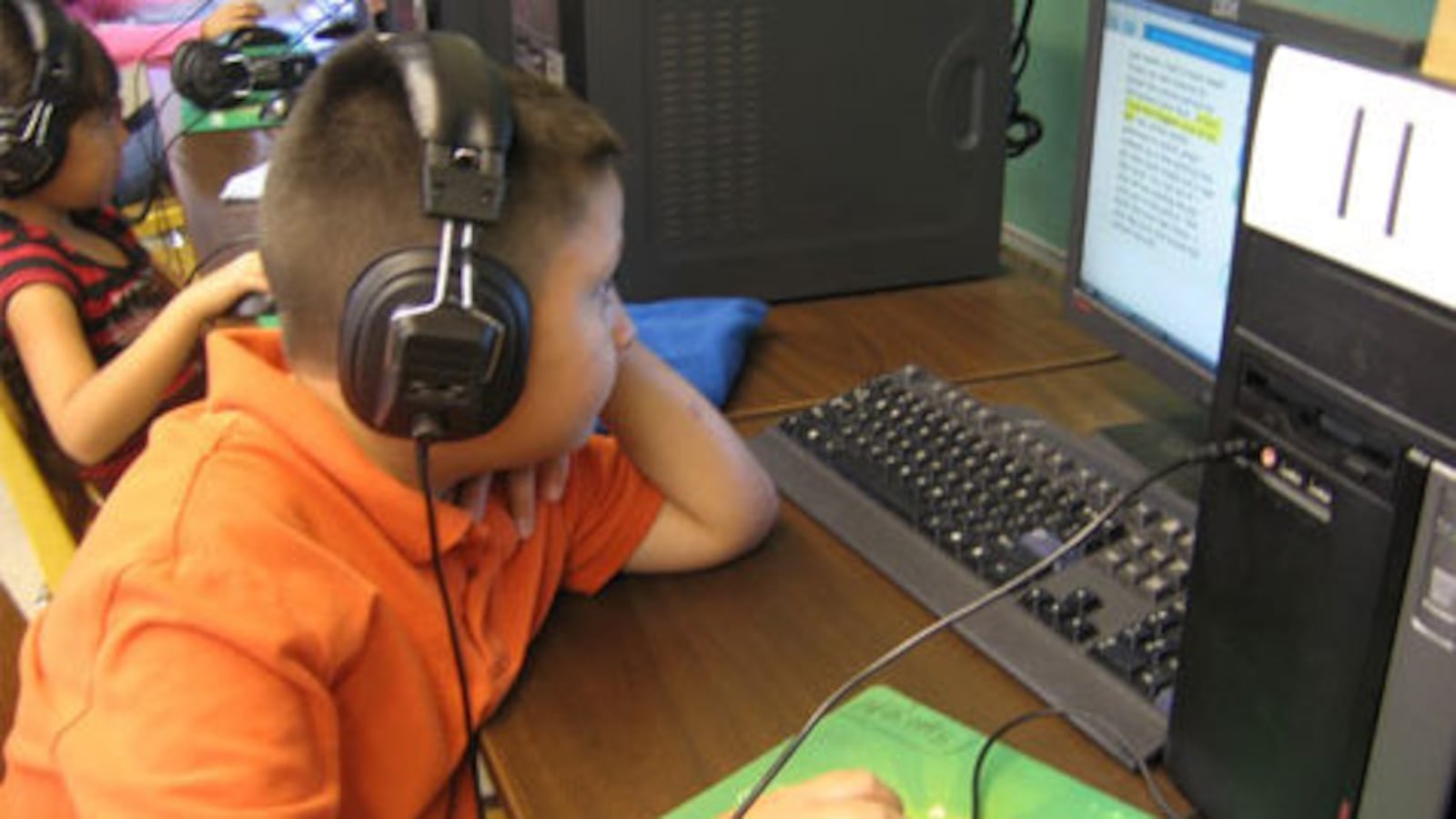

HOPE Online is authorized by the Douglas County school district as a multi-district online school. Students are required to attend brick-and-mortar learning centers daily where they work on online and offline assignments with the supervision of mentors and, in some cases, licensed teachers. HOPE has multiple learning centers across the state, though in the state’s oversight system, they are treated as one elementary school, one middle school and one high school. The elementary school serves 921 students.

Its model was part of the reasoning the state review panel, a group made up of educators and education experts, gave for recommending closure, suggesting that the school’s “blended learning” model mixing online and offline instruction is not unique and that students would be able to find similar schools that could better meet their needs.

HOPE officials believe they do offer a unique model, and some State Board members also defended HOPE’s approach, praising the engagement and caring of the adults at the centers. Board member Joyce Rankin said she has “never seen anything better than the people and the community of HOPE. It gives me hope.”

In 2017, the State Board directed the school to change its governing board and work with an external manager to help recruit and better train teachers, among other improvement strategies. Under that plan, HOPE was required to show improvement by 2019, but it failed to do so.

In their presentation to the state, HOPE officials cited their own data showing that they have made some progress, even if it hasn’t been enough to meet the goals set by the state. They also pointed to the challenges of their student population, about 87% of which come from low- income families, and about 54% are English language learners.

Bill de la Cruz, the vice president of HOPE’s governing board, said “standards don’t always fit the unique model” of HOPE and that the school needs more time to show improvement.

State Board President Angelika Schroeder questioned whether HOPE’s new board was doing any better at oversight, if it only meets quarterly. The review panel also found concerns with the school’s finances, noting that inadequate reserves put it in violation of state law.

Heather O’Mara, the school’s CEO, said that in 2017, HOPE’s board closed some especially low-performing learning centers and dipped into reserves to keep paying employees so that staff-to-student ratios would be lower at the centers it kept open. She said that as HOPE’s enrollment has been decreasing, the school likely won’t be able to replenish those reserves until 2021.

HOPE officials suggested that the State Board should order them to hire a new external consultant that would focus more on improving instruction, or that the state should save them by combining the elementary and middle schools into a single entity. Many of their learning centers already have combined elementary and middle school grades, and HOPE’s middle schools have shown improvement in recent years

State Board member Steve Durham said he was disappointed by the school’s presentation.

“I believe if the direction in which you’re headed is the direction which you’ve presented here today, I think it is a prescription for failure,” Durham said. He said the school was presenting its students as victims and making excuses for their low academic achievement.

“We have high expectations and there are no excuses for failing to meet them,” he said.

“I respect the safe and loving sites you create,” Schroeder said, but added, “they’re not learning. Nine years is a really long time for us to not think about making dramatic changes.”

Even then, most board members did not seem inclined to follow a recommendation to order the school to close. Thursday’s order to come back with more information passed on a 4-3 vote with members Rankin, Val Flores, and Rebecca McClellan voting no. McClellan was critical of the school and said she didn’t want to give it more time. Rankin and Flores support the school.

“I’m disappointed that we can’t just say go forth for one more year,” Rankin said.

O’Mara told the board HOPE would begin work immediately to determine if there is a high performing charter school that would be willing to partner with HOPE. They must then submit a report on how that might work.

HOPE will also have to report back in February about its contracts with the learning centers and how it might be able to change them to gain more control. The State Board expressed concerns that HOPE does not have the authority to hire or fire the mentors — they are employees of each center that contracts with HOPE — and did not appear to have clear data on the qualifications of those mentors.