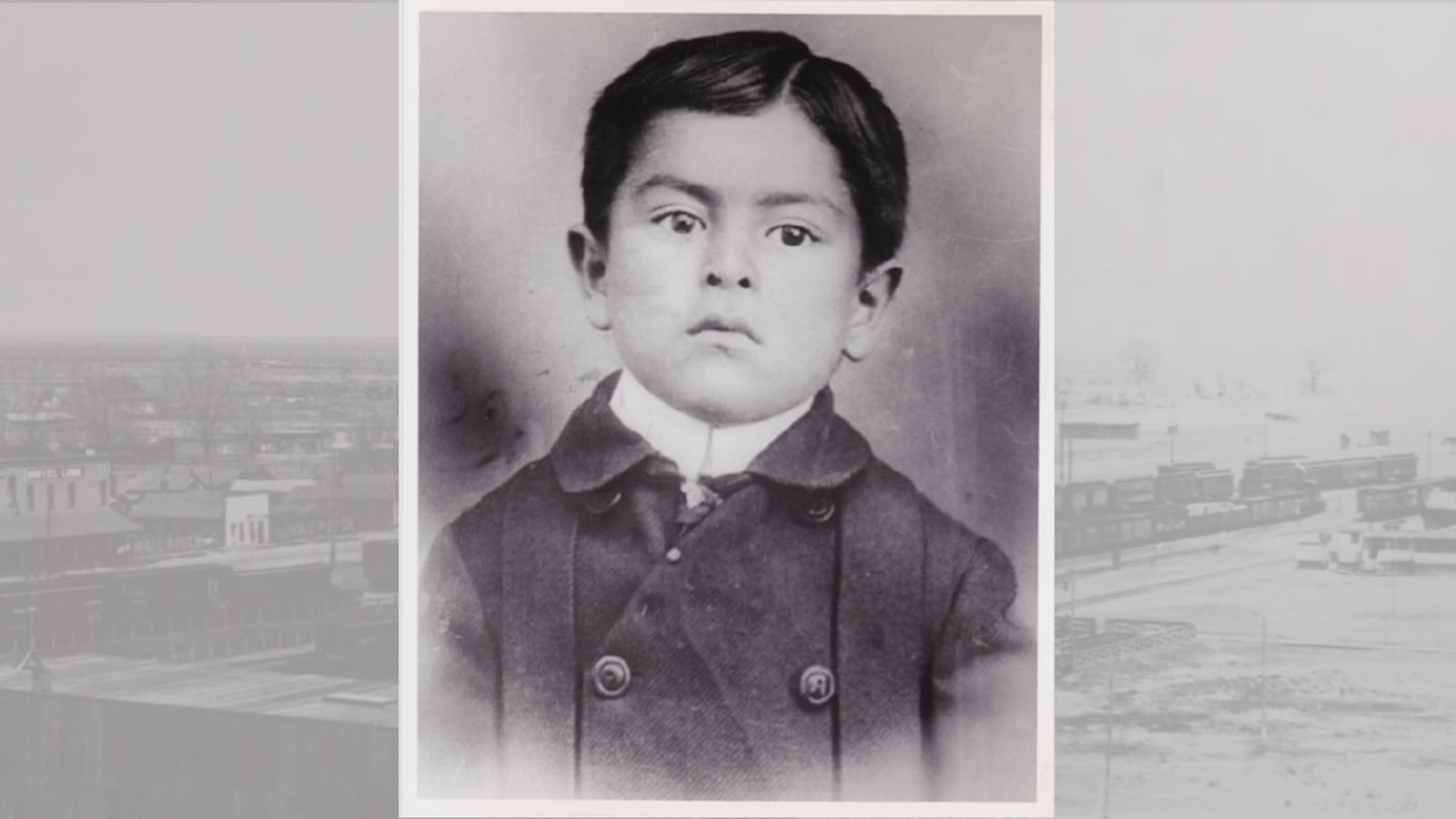

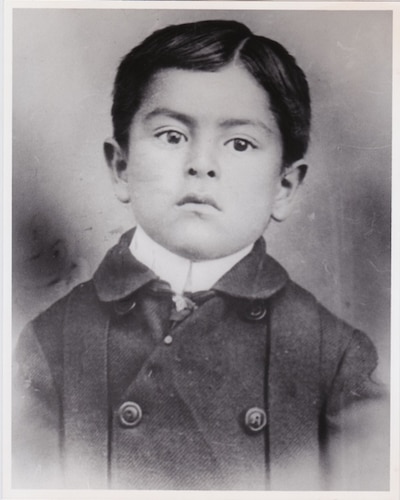

In 1913, a railroad foreman in Alamosa tried to enroll his 11-year-old son in the school closest to the family home. The school district denied him, and instead forced Miguel Maestas to walk seven blocks across dangerous railroad tracks to what was known as the Mexican School.

Maestas and other Mexican American families sued the southern Colorado district in what is the earliest known school desegregation case in the United States involving Latino students. They ultimately won the right to attend the same schools as the community’s white children. The case predates the Mendez decision, in which a U.S. District Court found that California could not send Mexican American students to separate schools, by more than three decades and other local court cases in Texas and California by more than a decade.

The Denver Catholic Register hailed the Maestas decision as “historic,” but because it was a local court case, it did not set precedent and was largely lost to time and memory until just a few years ago.

On Monday, a Colorado resolution recognized the importance of the Maestas case.

“We, the members of the General Assembly, acknowledge the tireless efforts of the Latino community in advocating for the integration of our public schools and improving outcomes for all students in Colorado,” the resolution concludes.

State Sen. Julie Gonzales, a Denver Democrat with family roots in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, and a co-sponsor of the resolution, said the Maestas case is an important reminder of Latino contributions to Colorado and to educational justice. Honoring it lifts up history and brings it into the present, she said.

“We hear celebrations of the Brown v. Board of Education case in 1954,” she said. “That is important history, but we were breaking that ground in Colorado a generation beforehand.”

Nationally, scholars say there is a shortage of monuments and memorials recognizing Latino history. In Alamosa, where the local newspaper drew attention to the Maestas case, community members raised money to build a monument, which will be unveiled later this spring.

Latinos have continued to fight, sometimes in the courts, for their educational rights, including access to bilingual education, sufficient funding for English language learners, and protections for immigrant students. The recognition of the Maestas case comes amid a broader national conversation about the value of integrated schools. Many schools in Colorado and around the country have become more segregated, particularly for Latino students, with school choice, charter schools, and gentrification adding complex new layers to the problem.

“It’s incredibly relevant to the sociopolitical environment we live in,” said Gonzalo Guzmán, a lecturer at the University of Washington who co-authored a paper on the Maestas case. “Particularly to show that the Latino community has been in a longstanding fight for educational justice and access. This did not just develop recently. It’s been going on for a long time. It also shows history as a sign of hope in action. It’s worth the struggle.”

The case appears to have been previously unknown even in academic literature. Guzmán encountered a passing reference in a Wyoming newspaper to Mexican Americans in Alamosa suing their school district while doing research on a different topic. In collaboration with other researchers, he started looking for information about the case in Colorado newspapers and other records and found a well-documented story, particularly in the Catholic press.

The account that follows is based on the paper that Guzmán published in the Journal of Latinos and Education with Ruben Donato of the University of Colorado Boulder and Jarrod Hanson of the University of Colorado Denver.

Guzmán said the Maestas case is distinct in that it played out far from the Mexican border, in Colorado’s San Luis Valley, and involved long-established Mexican American families, rather than a mix of older settlers and immigrants. Yet it shares features with other early desegregation cases involving Mexican Americans, including the ambiguous racial position of those communities and the use of language to justify segregation.

Sometimes known as the Hispano Homeland, the San Luis Valley is home to many families that can trace their ancestry to Spanish colonial settlements. Because they gained U.S. citizenship through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed at the end of the Mexican War, the courts often considered them to be legally white.

But that didn’t mean Anglo newcomers treated them as white. Mexican Americans were excluded from many public establishments, struggled to defend their historic property rights in court, and saw their children sent to separate schools.

The Alamosa district built its Mexican School in 1909 to provide instruction in both English and Spanish as larger numbers of Mexican Americans had moved to the city from northern New Mexico to work on the railroads.

But in 1912, a new school superintendent forced all Mexican American children to attend the Mexican School. Even then, Colorado’s constitution banned discrimination on the basis of race. When challenged, school officials said they were not discriminating on the basis of race — because Hispanic children were white. Rather, officials pointed to language differences to justify the separate school.

But many of the Mexican American children of Alamosa already spoke English, something Miguel Maestas and his classmates would later demonstrate in court.

The State Board of Education declined to intervene, citing local control. Mexican American families pulled their children out of school in protest and raised money to hire a lawyer.

In court, the district tried to argue it was acting in the best interest of students by giving them specialized instruction and that “race prejudice” had nothing to do with the separate school. But on the stand, one white school board member admitted he would not send his own children to school with Mexican American classmates. Throughout the trial, the two groups of students were consistently referred to as “Mexican” and “American.”

Miguel Maestas though “timid and abashed by reason of the crowded courtroom,” according to a newspaper account of the trial, easily answered questions in English. While the district had downplayed the distance involved, Miguel told the court that he was often late for school because he had to wait for passing trains.

The principal at one of the “American” schools in the district testified that students who were fully capable of doing coursework in English were removed and required to enroll in the Mexican School. Teachers at the Mexican School testified that most of their students spoke English but that the school board required them to use Spanish.

One Mexican American father testified that when he joined others in petitioning for their “constitutional rights,” a school board member responded that they “had no rights.”

Ultimately, the judge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. “The only way to destroy this feeling of discontent and bitterness which has recently grown up,” he wrote, “is to allow all children so prepared to attend the school nearest them.”

This was not a complete victory. The Mexican School continued to operate under a new name, and records exist of the judge later issuing orders regarding individual children, allowing some to attend the community schools and keeping others in the separate school until their English improved.

The plaintiffs’ attorney was not satisfied. “It is still our contention that even though totally deficient in a knowledge of the English language, children cannot be placed in a separate race school in Colorado on that ground,” he told the Denver Catholic Register. Doing so was “getting perilously close to separation on account of race.”

The complicated intersection of race, ethnicity, and language is a recurring feature of school desegregation cases involving Latino students.

Guzmán said he hopes attention on the Maestas case inspires other scholars to keep digging.

“This was a needle in a haystack in a haystack in a haystack,” he said. “This shows how much there is to know and find out about our nation’s history. This case is over 100 years old. It could have easily been lost to the annals of time.”