In the first week of virtual learning, two Aurora co-teachers shared visual presentations about themselves with the high school students with special needs they teach.

Teacher Dawna Pickett used a PowerPoint that included photos and tidbits about her, her family, and her hobbies.

Then the teachers asked students to do the same. Students submitted videos, PowerPoints and presentations in multiple formats. Even one student who was out of town for the week still submitted a presentation from her phone.

“I got back fabulous presentations,” Pickett said. “I gave them the option, if they wanted to present it to the class or if they just wanted to share it with me. But because it’s virtual and they’re not having to stand in front of class, they didn’t mind presenting to everybody. That fear factor of standing up in front of everybody is not there.”

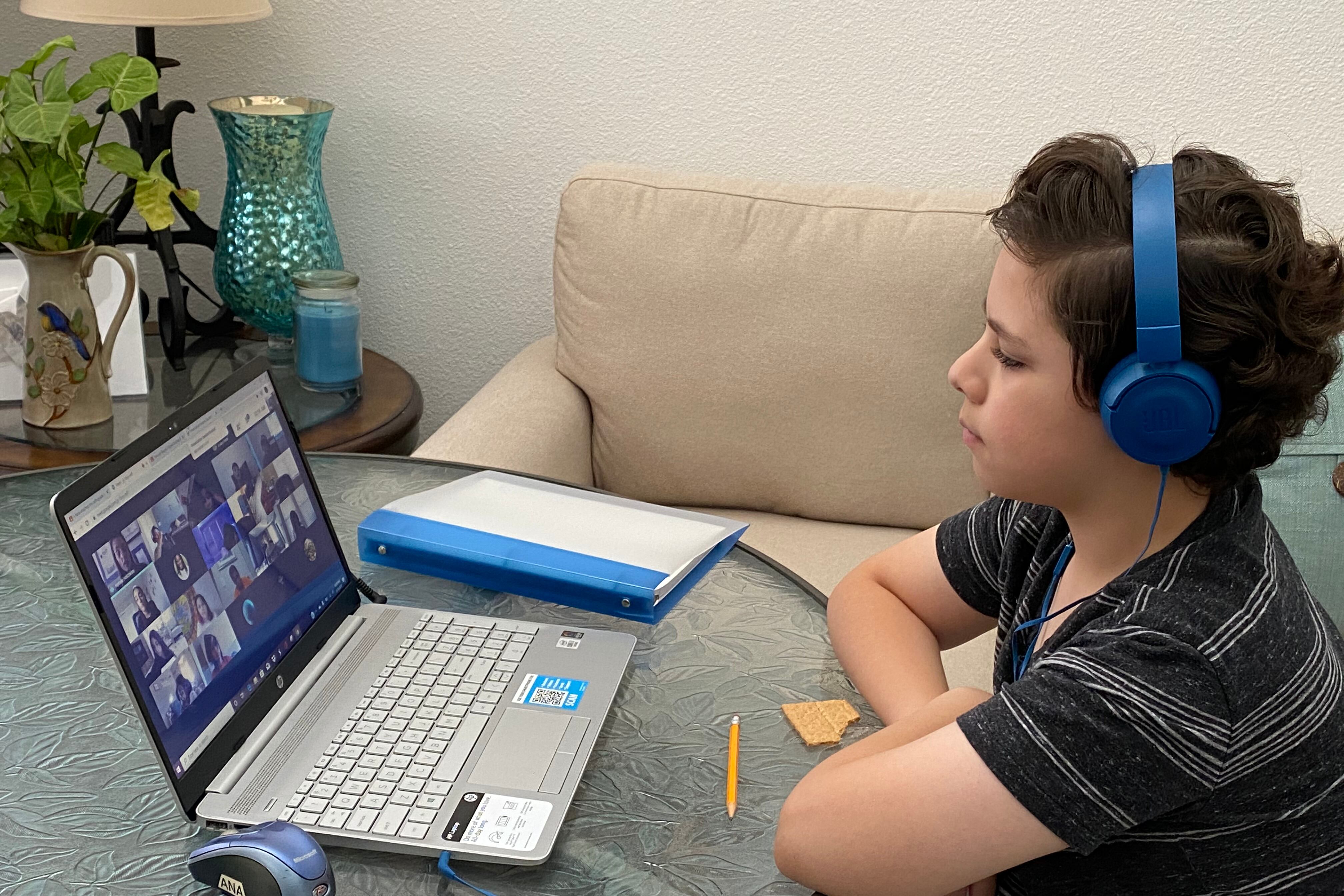

Aurora classes started last week, about a week later than first planned. All classes will be online through the first quarter.

Pushing back the start of school gave teachers about eight days of training and preparations. There were about two days of district led virtual trainings. Then there were specific school-level trainings for teams often more focused on specific content or technology. And then there was time for teachers to plan their lessons and play around with new online programs they might use for different lessons.

A big focus of district preparations, teachers said, was on creating relationships with students, and on learning the neuroscience explaining why high levels of stress impact a child’s ability to learn.

Many Aurora classrooms kicked off the school year by focusing on making time for one-on-one check-ins with students, which normally might happen naturally in a hallway, but now have to be scheduled virtually. Teachers also conducted traditional ice breakers, asking about a favorite food or restaurant, and what went on over the summer.

“It felt very good to me that leadership in the district was putting the emphasis first on relationship building and community building with our students,” said Linnea Reed-Ellis, a third-grade teacher in Aurora.

Teachers said that district leaders pointed out that they should be aware that the pandemic, and also the movement for racial justice surrounding the murder of Black Americans, including Elijah McClain locally, could be weighing on many students’ minds.

But for some teachers, the acknowledgement lacked concrete ideas for how to have those conversations with students of different ages.

“That would be the next step I would really look for,” said Reed-Ellis.

As in many districts, the majority of Aurora’s teachers are white, while the majority of students are students of color. Aurora is one of the most diverse districts in the state, with a high number of students coming from immigrant and refugee families.

Having a safe place to address traumatic experiences is top of mind for many parents, but getting more learning time and attention from teachers has also been a concern from families who weren’t so pleased with how the last year ended.

In the spring, when districts closed their buildings, Aurora did not require most teachers to provide instruction to students. In elementary and middle school district officials said they focused on “access.”

That means the district distributed technology, and created a website where students could find work to do. Teachers were checking in with students, and often pointed them to the website and suggested activities to do from there, but were told they did not have to create their own lessons.

The district directed most high school students to online credit-recovery courses, so they wouldn’t fall behind on graduation requirements.

As the district planned for a new school year starting with remote learning, leaders said things would change and touted a more robust program — even though until less than a month ago they were preparing for a return to in-person classes.

This time, teachers are creating virtual lessons, including for a lot of live interaction throughout the day Mondays through Thursdays. Some district training focused on helping teachers figure out when a lesson should be live or left for independent work, and figuring out which online tool might be helpful.

Teachers said they plan a slow pace in the first weeks as students still deal with internet connection issues and learn how to use new online programs.

Fifth grade teacher Peter Zola said this week he’ll try to gauge where students are academically, but in a deliberate way that informs each day’s lessons.

“We’re thinking of just trying to take the temperature of what they need on the day,” Zola said.

Anecdotally, teachers reported higher-than-expected attendance and participation. Family liaisons, paraprofessionals, and other school staff are tracking down students who did not log on to their classes last week.

“Kids and families are ready to have school again — that’s the perception that I’m getting,” teacher Reed-Ellis said.

She said her school sent out community navigators, including one who spoke Swahili, to a Swahili-speaking family’s home to help the student and parent log on and learn the technology in person as classes started online.

In other cases, teachers have had some frustrations with technology, especially as they try to focus on equity for all students.

“Aurora decided to use Google Meets instead of Zoom and it is not up to par at all,” said sixth grade teacher Nicole Kaiser. “That’s been frustrating.”

Many school districts have discouraged the use of Zoom due to privacy concerns and other factors, but the decision comes with trade-offs.

With Zoom, Kaiser said she could record classes for students who missed them, break students up into smaller groups, and automatically mute all students entering the Zoom class. She’s also worried about students without a good internet connection.

“How do we still give all students equity but really we still have spots in the city where you have no internet,” Kaiser said. “I’m in a classroom with a hotspot.”

Teachers said they have also been concerned about having less time to collaborate with each other.

Before the start of school, teachers said they participated in most training from home, watching prerecorded webinars by themselves. And as school started, there’s no opportunity to walk across the hallway to check in and talk with other teachers.

“If we were able to meet as groups, virtually, I think that would have been a lot better,” Pickett said. “I don’t even know all my coworkers yet.”

Part of Pickett’s job as a special education teacher is to help other general education teachers working with her students to understand their individual needs, plans, and how to make accommodations for them. This year, she’s emailed those details to teachers, but missed having sit-down conversations with each one about her students.

Kaiser, as a general education teacher, also said she was still waiting to get to talk to the special education teacher at her school, to learn more about her students and their individual needs.

“It does seem like we had a lot of training before school started and the start of school just came up on us too fast,” Pickett said

Overall, teachers and many parents still said the start of the year went better than expected.

Stepping into week two, teachers said they will largely focus on continuing to create connections with students. Those connections will have long-term impacts on learning, teachers said.

“I’m really more worried about two or three weeks from now,” Zola said. “I’m worried about students checking out and disengaging then. We need to build strong enough connections that kids want to be in class.”