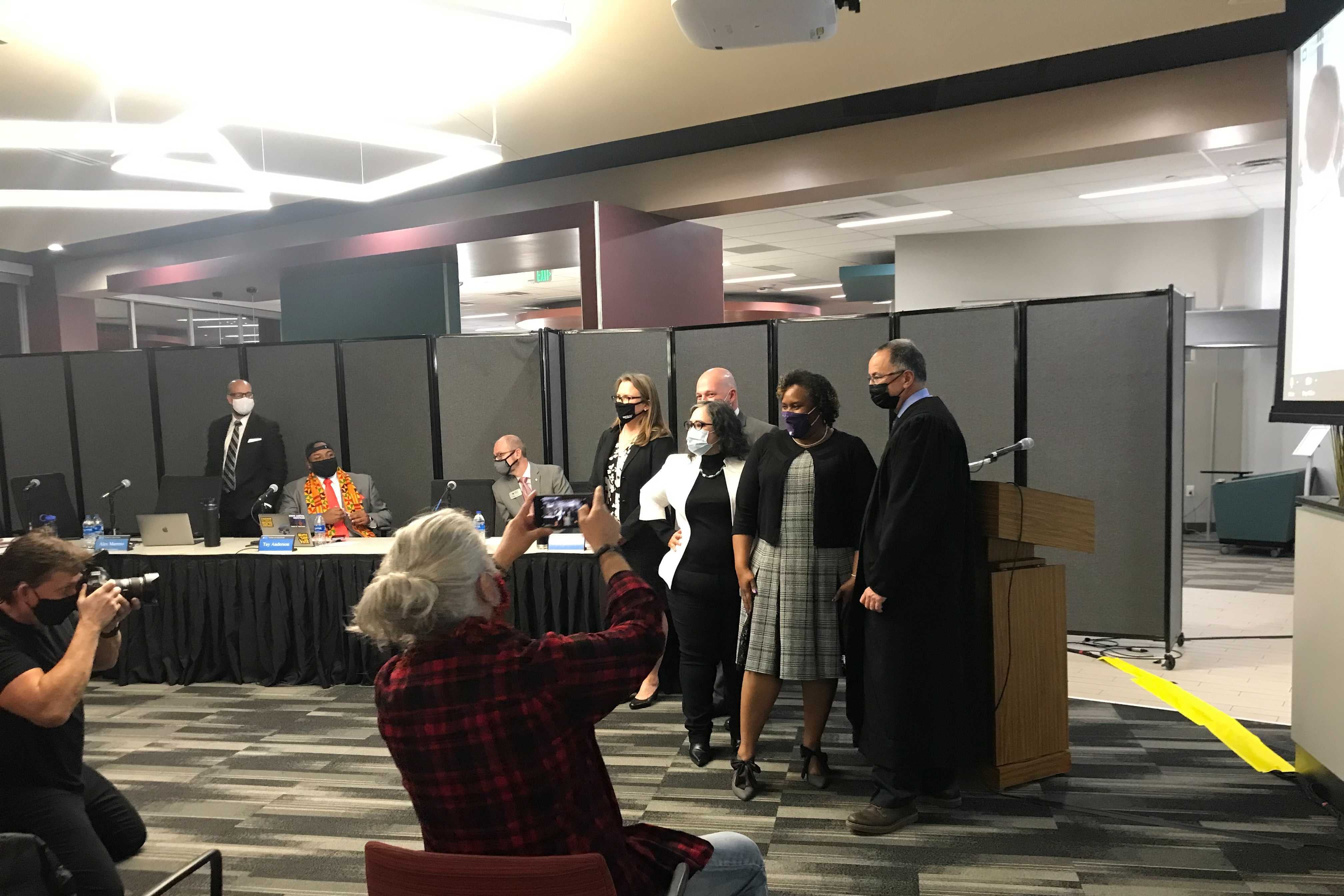

Denver’s newest school board members were sworn in Tuesday and immediately elected to leadership roles, a move that marks the completion of a political “flip” that puts board members supported by the teachers union and critical of past reforms in unanimous control of the district.

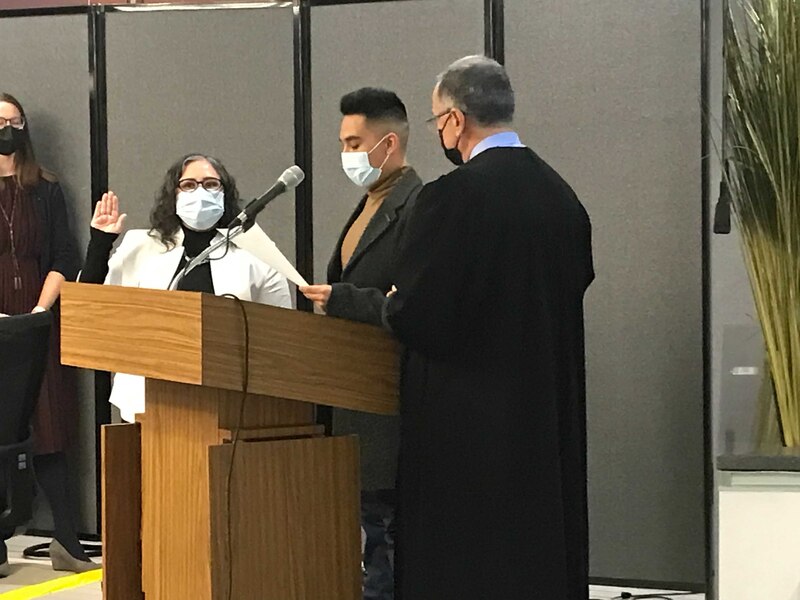

Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán, a graduate of Denver schools and a parent from southwest Denver, was elected president of the board by secret ballot. Gaytán replaces former president Carrie Olson, who was first elected to the board in 2017 and won re-election to her board seat this month. Olson was also nominated. The board did not announce the vote tally.

While Denver’s school board has long stated a commitment to improving education for the students of color who make up the majority of the district, the newly elected board members have explicitly called for the need to dismantle racist systems of oppression.

“We have work to do,” Gaytán said. “We know that the employees and the staff of all of Denver Public Schools are working within a racist system.

“And we board members are working within our own racist system, and so we have work to do there as well as we begin to dismantle some of those processes and procedures so that we begin to move forward as we set a stronger and better foundation for quality learning.”

Tay Anderson, who was elected to the board in 2019, was chosen as vice president by secret ballot over Olson.

The move was a vote of confidence in Anderson two months after he was censured by the previous board following an investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct. The investigation found that allegations of sexual assault were unsubstantiated, but he was censured for other conduct uncovered by the investigation.

Many other school boards select their officers through an open vote, but state law allows the use of a secret ballot for president and vice president. Denver has used secret ballots to select officers in the past.

The president and vice president of the board have significant power to set the agenda for the board and meet more often than other board members with the superintendent.

Michelle Quattlebaum, a Denver Public Schools graduate who works as a family and community liaison at her children’s alma mater, George Washington High School, was elected board secretary. Per board policy, Quattlebaum will have to resign from her district job in order to serve on the board. She represents northeast Denver.

Scott Esserman, a former teacher and current Denver parent, was elected treasurer. Esserman is an at-large member representing the entire city, as is Anderson.

“Denver Public Schools has over a $1 billion budget,” Esserman said. “And how those dollars are spent is a moral statement. And the moral statement that we’ve been making hasn’t been adequate. It hasn’t been acceptable for our Black students, for our Latino students, and that has to change. That has to change with a sense of urgency and immediacy.”

November’s election was momentous. Four years ago, all seven school board seats were held by members supportive of education reform. Now, the opposite is true. Also notable is that the union-backed candidates won on Nov. 2 despite being massively outspent.

Organizations supportive of reform spent at least $1 million on a different slate of candidates who were more favorable to independent charter schools, according to campaign finance reports that track spending through late October. Teachers unions spent less than half that.

Experts said school board election results tend to be specific to each community, rather than driven by national trends. However, Janelle Scott, a professor of education at the University of California Berkeley, said opposition to the politics of former President Trump and his education secretary, Betsy DeVos, have fed a backlash against the concept of reform.

Though the intent of reform was to improve education for students who were poorly served by the status quo, many on the left saw DeVos’ policies as undermining public schools and promoting privatization. People and organizations that cared about educational change but “came at it from an articulated position of equity and social justice said, ‘Wait a minute, we disagree with so many of Trump’s positions, we feel uneasy being associated,’” Scott said.

That unease was likely at play in the Denver school board elections this year and in 2019, when union-backed candidates swept all three open seats, flipping the board majority.

“I do feel like the Trump era and Betsy DeVos played a role in ‘us-versus-them’ conversations that were more national and more partisan than the reality of the Denver school board,” said Krista Spurgin, executive director of Stand for Children Colorado, which endorsed a mix of reform and union-backed candidates this year. Spurgin said it’s “easy for the electorate, which in Denver is quite left and progressive, to assume one side versus another.”

Paul Hill, founder of the Seattle-based Center on Reinventing Public Education, said he doesn’t see the election results as a wholesale rejection of reform, and he expects some aspects — such as school choice and charter schools — will continue to enjoy some support.

“Generally, public opinion swings on education are not that powerful,” he said. “It might be enough to change a board composition, but if that board shoves its point of view too hard, it finds people don’t want to follow them.”

Yet even before this election, the Denver school board had rolled back some policies associated with education reform. The board stopped closing schools due to low performance and reunited comprehensive high schools in communities of color that had been split up due to low test scores. The board also took a more skeptical stance toward charter schools and got rid of the district’s controversial system for rating schools.

Vanessa Quintana, a Denver Public Schools graduate and education activist who briefly joined the race as a candidate but then withdrew, said she sees the new board members as more than anti-reformers. She hopes they will be transformers bent on dismantling systems of oppression who will listen to community members and work with other elected officials to create change.

“I just hope [on Tuesday] that they tap into their ancestral connections, take some time to reflect, to be alone, and listen to their soul,” Quintana said. “There’s a lot of possibility.”

After being sworn in, Gaytán said the new board, which includes members Scott Baldermann and Brad Laurvick who were elected in 2019, is united in their call for change.

“This new 7-0 board is aligned so well with the protection of public education,” the newly elected board president said. “This is a new era for Denver Public Schools.”