Figuring out how to measure a school’s performance in the absence of state testing data means focusing on the work of educators.

In a required update to the State Board of Education Wednesday, staff from the Colorado Department of Education focused on that work — and not student achievement — as they looked for new ways to understand the pandemic’s true toll on students in the lowest-performing schools.

Monitoring progress at these 12 schools and two districts on state improvement plans highlights the dilemma education officials across the state and country face as they try to assess student progress and learning loss without state standardized testing data. That leaves internal district assessments as the main data source. Colorado waived standardized testing last year, and it’s unclear whether those tests will resume this spring.

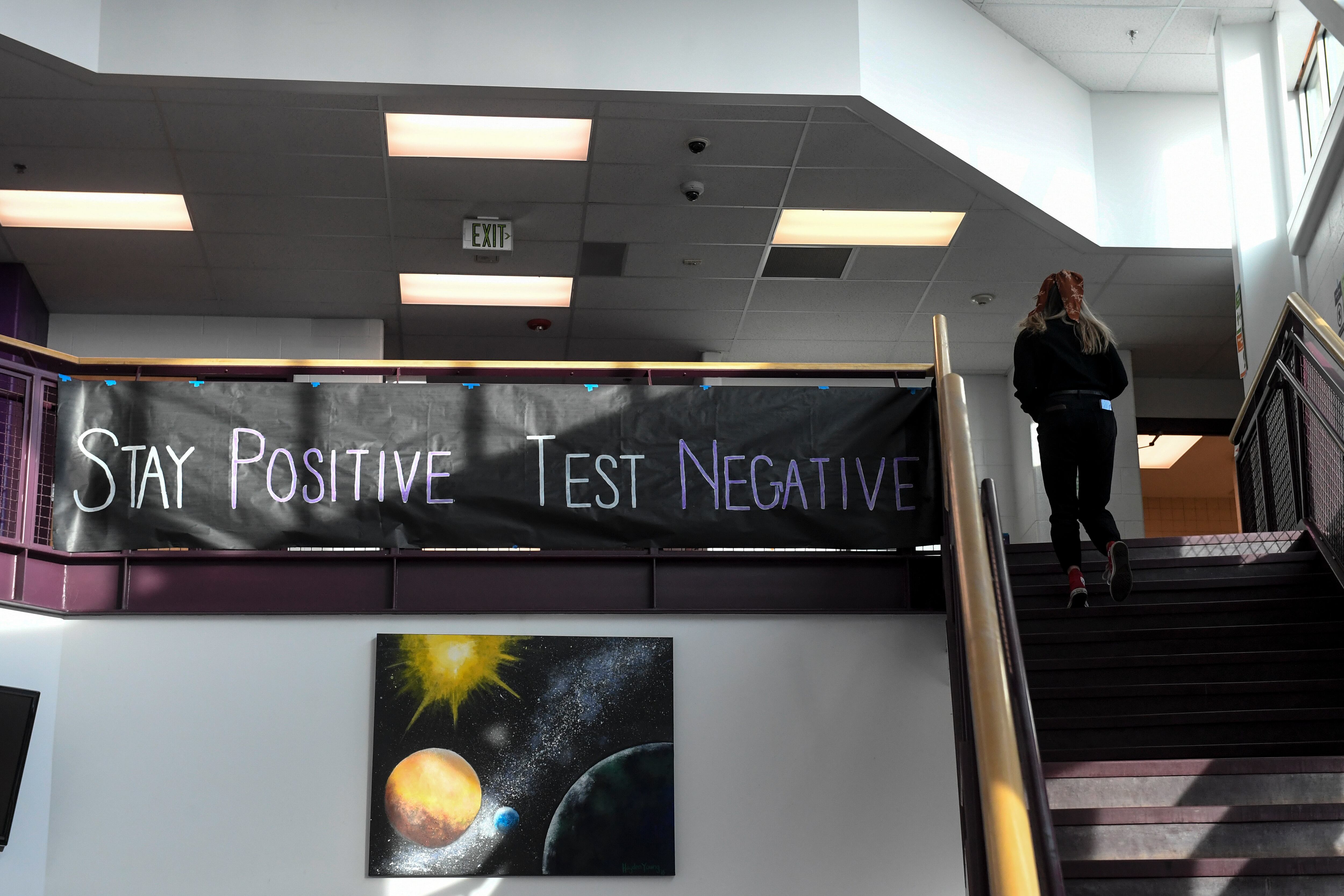

Without that clearer data, state officials highlighted school and district leaders going above and beyond during Wednesday’s progress update. They described administrators who made house calls, teachers who rolled out a red carpet for students returning to school buildings, and a softball team that persevered after thieves stole the school’s equipment.

State officials said they focused on inputs, including whether improvement plans were still being followed.

“Those systems and structures and the strategies they were putting into place for their improvement, they are doing. They are continuing to do those things,” said Lindsey Jaeckel, executive director of school and district transformation for the Colorado Department of Education. “How that translates to their student achievement benchmarks and things like that remains to be seen.”

Staff from Adams 14, the only district in Colorado under full external management, also gave an update to the State Board Wednesday. They showed some interim district test data, mostly administered while students learned from home. And although there are some areas of improvement, district officials noted they have failed to reach their own internal targets for improving academic achievement.

For example, Shelagh Burke, the district’s chief academic officer, said that Adams 14 lowered the number of struggling readers on READ plans by 19%, falling short of the 25% goal the district had set.

Officials from Adams 14 and MGT Consulting, the for-profit management company running the district, emphasized that the pandemic hasn’t derailed the improvement plan.

The school board has now finished Adams 14’s new vision and mission and agreed to four overarching goals to guide the district’s future work.

The board this month also opened a search for a firm to help hire a superintendent who would start this summer. Adams 14 has not had its own superintendent for almost two years, during which MGT filled that role with Don Rangel, previously a superintendent in Weld County.

“We have really worked hard to have this look, sound, and feel like a partnership,” Rangel told the State Board of Education. “We know in the future as MGT begins to step away a bit, more and more of that responsibility will rest completely with the district. And I really believe that they’re going to be in a position to move forward with that.”

The Adams 14 district has been under state oversight for nine years now. The state’s current order gives MGT another two years to help turn the district around. Although the district’s own school board had brought up potentially asking for more time to improve given the COVID-19 disruptions, that issue didn’t come up on Wednesday.

During the progress meeting, board members specifically cited concerns with graduation and attendance rates, wondering how they compared with other years.

“I am troubled by the new definition of attendance,” said board Chair Angelika Schroeder. “If you’re remote, you turn your machine on, and you’re there. It’s not a meaningful data piece for us at the moment.”

Jaeckel admitted that there is a lot of variation in how schools and districts measure attendance and engagement. But, she said, this group of schools is really on top of tracking engagement.

“I don’t know that I’ve seen anything that tells us that the kids are on track in terms of the learning,” Schroeder said. “This isn’t a rosy picture in terms of the outcomes for our kids. We should give a lot of respect and kudos to all of the educators for really trying to do the work that they said they were going to do that was going to make a big difference.”

But it doesn’t mean we know if it’s going to pay off for students, she said.

State officials noted that Aguilar, the other district under the state’s watch, as well as at least one other school, Minnequa Elementary in Pueblo, do have interim data that appear to show academic improvements made over the last year. In both cases, however, state officials noted that students have had more access to in-person learning than students elsewhere.

Still, “they’re optimistic and we’re optimistic,” Jaeckel said.