Alicia Garcia was cleaning up the remnants of the cupcakes she’d brought in for her daughter Eliyana’s 7th birthday at Denver’s Newlon Elementary last March when she heard the schools were closing for an “extended spring break” in an attempt to slow the spread of COVID-19. At that point, there were 49 cases in all of Colorado.

“The teacher was like, ‘Okay kids, go to the [classroom] library and take as many books you want to take,’” Garcia recalled. “It was crazy.”

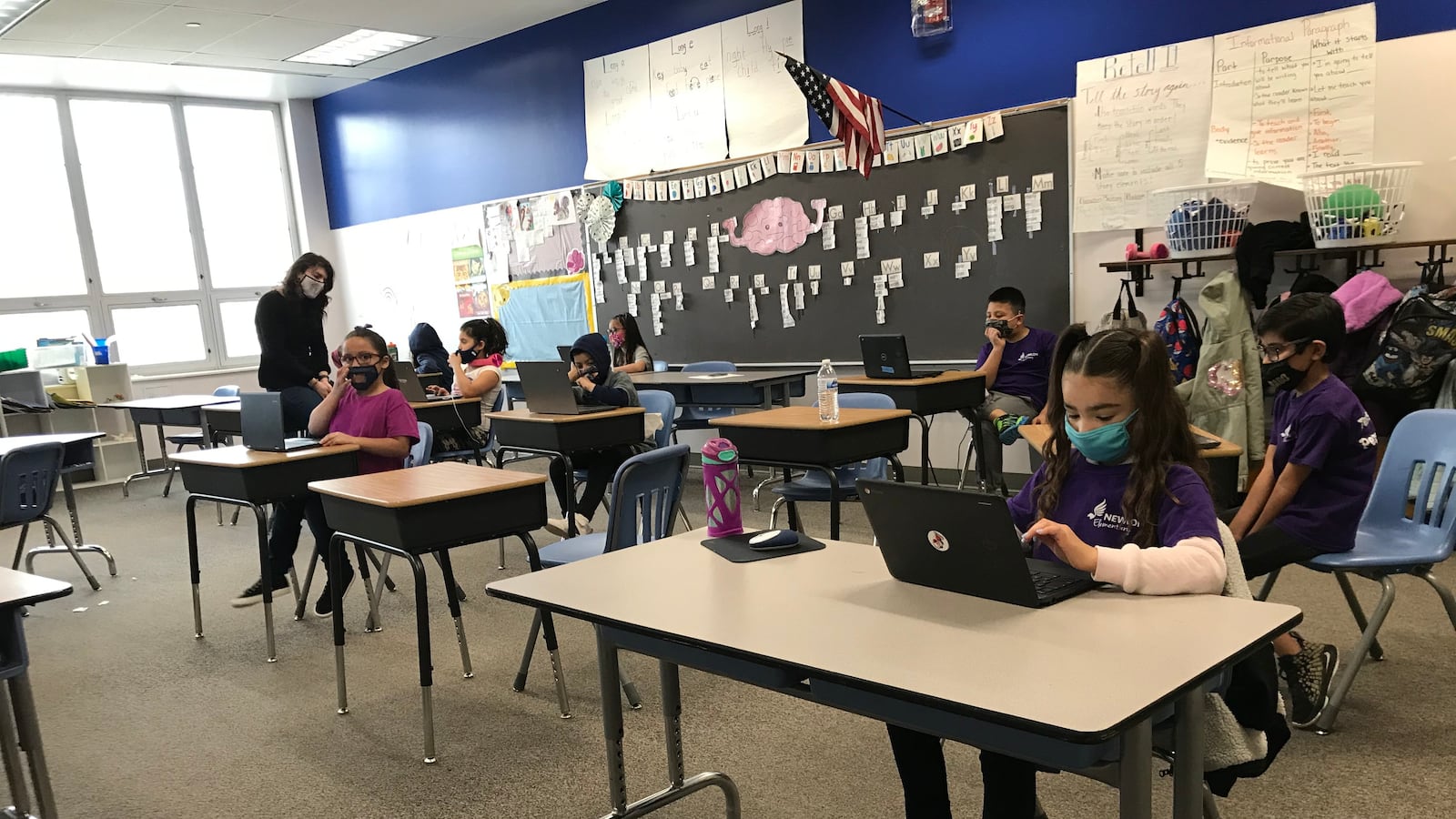

What began as a three-week break has turned into a year learning at home for Eliyana, now a second grader at Newlon. The close-knit school in a working-class southwest Denver neighborhood, where 95% of students are Hispanic, is open five days a week for in-person learning. But about half of its 300 students are learning from home, a reflection of the greater skepticism about returning to classrooms among communities of color.

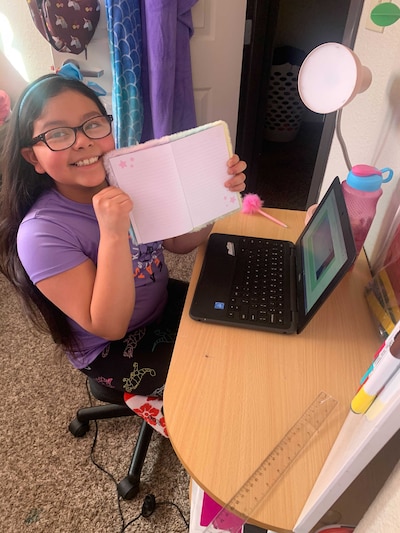

Like many of her classmates, Eliyana has been learning to spell compound words and add dollars and cents from her bedroom. Her mother works as a caregiver for Eliyana’s great-grandmother, and the family can’t risk any exposure.

“I never ever imagined this. I never thought we would live through this,” said Garcia, who was an active parent volunteer before COVID, bringing her newborn son with her to PTA meetings. “It was hard on all of us because everybody was so close and it was taken away so fast.”

The past year has been difficult for all schools in Colorado, a state where there have been more than 436,000 cases of COVID and 6,000 deaths. In the absence of a statewide strategy or mandate, each of Colorado’s 178 school districts have made reopening decisions on their own.

Denver Public Schools, the biggest district in Colorado with about 93,000 students, has taken a fairly cautious approach. Denver started the school year virtually, and then opened and closed school buildings as cases rose and dropped. But the volume of families choosing to stay remote at elementary schools like Newlon even after students were welcomed back full time has been an added challenge for teachers, who had to adapt to instructing students seated in front of them at the same time as those behind laptop screens.

Eliyana’s teacher has discovered a surprising upside, however: a strengthened relationship between parents and teachers, who are truly partners in educating the students.

“Parents will text me and say, ‘They’re not understanding how to make the ‘oo’ sound in ‘book.’ Can you double check in with them tomorrow?’” second-grade teacher Callie Gonyea said.

That level of communication was not something Gonyea had experienced in her 5-year career.

“A lot of the time, parents are used to teachers talking to them,” she said. “They’re not as used to teachers listening to them about areas they feel a student might need a little help.”

On any given day in Room 116 at Newlon, Gonyea is juggling teaching 18 students in person and eight at home. With a computer propped on top of an upside down trash can, and a speaker and camera balanced on top of a bucket, she keeps a running tally in her head: for every two students she calls on in class, she taps one at home.

“Who’s going to be my first friend to show me their board or put it in the chat?” she said to the remote students during a phonics lesson last week. Her class was practicing writing the compound word “countdown,” in which the tricky “ow” sound is spelled two different ways.

The students in class were writing the word on mini whiteboards. The kids at home had whiteboards too, but most had their cameras off, preferring to type their answers. Of the students whose cameras were on, one was lying on a pillow in her bed. Another was wearing headphones in a room with a sibling. A third was eating breakfast.

Gonyea called on the girl who was eating to spell another compound word: “underground.”

“What part do you see in the word ‘ground’ to help you out?” she asked.

There was a long pause — 12 seconds, longer than most teachers would wait under normal circumstances — as the girl figured out the answer and then clicked the unmute button.

“The ‘ow’ sound?” the girl finally said.

“The ‘ow!’” Gonyea repeated. “And what letters make that ‘ow’ sound?”

Still unmuted, the girl answered quickly. “O-u?” she said.

“O-u!” Gonyea acknowledged.

This type of simultaneous teaching is a far cry from what Gonyea and other teachers were doing last spring. Instead of live video calls that spanned the school day, Gonyea assigned three literacy and three math lessons per week. She recorded short five-minute videos explaining the assignments and let students complete them at their own pace.

But many students struggled with the technology, Gonyea said. The school was eventually able to distribute enough laptops and get most families connected to the internet, but Gonyea’s second-graders didn’t know how to type on a keyboard or toggle from one tab to another.

“It didn’t feel a lot like teaching, what we were doing,” Gonyea said. “I spent a lot of time thinking about, ‘Am I doing enough? What more can I be doing?’”

Gonyea spent most of her days calling families. It was a schoolwide strategy to check in with each family at least once a week. Newlon was finishing up a four-year grant on improving social and emotional learning, and Principal Rob Beam said the focus “was to keep that alive, almost before instruction. Nobody learns well when they’re scared.”

If the academic part was stressful, Gonyea said improving her relationships with families was a silver lining. “When I’d call to check in, I’d ask, ‘What did you do over the weekend? What’s something you’re looking forward to?’” she said. “It allowed me to get to know them even more as people. ... You get to know your students very well, but you don’t have a dedicated time to have a 5-minute unstructured conversation with every kid twice a week.”

It’s an approach she’s carried into this school year. Although she no longer has the time to call each student twice a week, Gonyea spent the entire first week of school getting to know them and their families. She started by reading a book called “Alma and How She Got Her Name,” about a father explaining to his daughter the origins of her very long name.

Gonyea then had the students interview their families and write reports about the origins of their own names. When Gonyea made those first phone calls to families in August, she used the name origin stories as conversation starters with parents.

Jessika Espana remembers her daughter Isabelle being slightly disappointed to learn her parents chose her name to match her older brothers’, which also begin with “I.” Espana convinced her daughter to write about the nickname her family calls her at home: Chabelita. She remembers Isabelle giggling when Gonyea said it on the call.

Espana, who has two children at Newlon, has noticed the difference in the level of communication between parents and teachers. She said she appreciates that Gonyea always answers her questions, even if she texts late in the day.

“We didn’t have teachers’ phone numbers last year or any year before,” Espana said. “This year, I have all my kids’ teachers’ phone numbers in my phone.

“I go through the M’s and its ‘Miss this’ and ‘Miss that.’”

Alahnna Salcido went back to Gonyea’s class in person this fall, but when coronavirus cases began spiking in October, her mom switched her to remote learning for the rest of the year.

Alahnna is a loving 8-year-old whose mother, Angelique, describes her as “a real joy.” She’s also a motivated student. Learning from home, Alahnna said she misses playing with her friends at recess but she’s grateful she still gets to draw in virtual art class. She recently drew a story about a caramel ice cream cone named Carmy whose friends didn’t like him at first because he was different. But Carmy told them it’s important to accept everyone the way they are.

An upside to remote learning, Alahnna said, is that it’s easier for her to see the teacher’s screen at home than it was in the classroom, spaced 6 feet apart and wearing a mask. It’s also easy to participate in class discussions and answer Gonyea’s questions, she said.

“I like to unmute so I can share my ideas with speaking, but I also like [using] the chat because whatever I’m talking about to describe, I can use the emojis,” she said.

Gonyea’s second-graders are now whizzes at typing and tabs. They easily mute and unmute themselves on Google Meet and use the “raise hand” button when they have something to say. And the academics are going much smoother. Gonyea has gotten through more of the curriculum this fall and winter than she did last year before COVID-19.

“There was part of me that was fearful that with all of this weirdness going on in the transitions and the schedule: Would there be learning?” Gonyea said. “It looks different, but it’s still very much there. I’ve seen reading levels go up a lot. I’ve seen students come out of their shells socially and emotionally. That makes me feel good.”

Gonyea said she’ll never look back on this year as the best of her career, but she appreciates how it challenged her, made her grow, and helped her prioritize what’s most important.

“I don’t think I will ever go back to the way I interacted with families before,” she said. “I think I will now always be a teacher who is reaching out to families as much as possible.”

Beam, the principal at Newlon, said he’s seen all of his teachers grow tremendously in the face of adversity, even if the teachers themselves might not realize it yet.

“Teachers now are much better at their jobs than they’ve ever been before — they just don’t know why or how yet,” he said. “And we need to give them a chance to catch their breath.”

Eliyana, the student whose classroom birthday celebration coincided with the beginning of the pandemic in Colorado, is set to turn 8 on Sunday. Since she’s learning from home, she won’t be able to eat cake with her classmates in person this year.

But her mom has come up with an alternative: She plans to call Gonyea and ask if it’s possible to leave some boxes of cupcakes outside the classroom door.