The Denver school district will pilot a screener for dyslexia this fall after years of public outcry from frustrated parents, recommendations by school district working groups, and a delay caused by the pandemic.

And Denver’s pilot isn’t the only one. The Boulder Valley School District launched a dyslexia screening pilot at 10 schools last fall that has already screened 345 kindergarteners.

A state pilot program may also launch in the coming months, but a dearth of applicants makes its fate uncertain.

Colorado education officials were set to select five elementary schools for the one-year, $92,000 pilot program in late April. By the application deadline Friday, just five schools had applied, and state education officials are still determining if they all meet participation requirements.

New dyslexia screening efforts in Denver and Boulder — plus the possible state pilot — come amid a nationwide push to boost reading achievement, including by paying closer attention to students with reading-related disabilities. Experts estimate that dyslexia affects 5% to 15% of the population. In Colorado, that could be more than 100,000 school-age children.

Dyslexia is a learning disability that impairs reading. People with dyslexia have difficulty identifying speech sounds, decoding words, and spelling them.

“These are kids who can’t distinguish ‘eh’ and ‘ih’ in ‘pen’ and ‘pin,’” said Robert Frantum-Allen, the special education director for Denver Public Schools, who has dyslexia himself. “You can throw letters at them, but those letters don’t stick because they seem interchangeable.”

The three pilot programs cover different grade spans and use different screening tools. The Denver and Boulder pilots include Spanish-language assessments for English learners, while the state pilot does not.

In Denver, parents for years have asked the district for two things: A better way to screen students for dyslexia and the use of science-based methods to teach reading.

In September 2019, Nicole Wallerstedt told the school board about her daughter Finley. The year before, Finley had fallen off “the third-grade cliff,” her mother said. Third grade is when many students shift from “learning to read” to “reading to learn.” Finley fell behind.

It was a year of tears, social anxiety, therapist visits, and missed days of school. Wallerstedt said she watched her loud, outgoing child become withdrawn. An eventual diagnosis of dyslexia, which led to help and accommodations in school, brought Finley back, she said.

“Imagine how different it would have been for Finley if she got screening out of kindergarten and [her dyslexia was] caught early,” Wallerstedt said. “It would have taken the shame away from it. It would have given a plan. There would have been no stigma.

“And there hopefully would have been no third-grade cliff to fall off of.”

‘No ill intent’

Earlier in 2019, a Denver task force of parents, educators, and advocates for people with disabilities had recommended that all students entering the district be screened for predictors of future reading problems, including dyslexia. And in April 2020, a district working group recommended piloting two particular screening tools.

The group suggested screening all kindergarten and first-grade students at 20 schools using a tool called Shaywitz DyslexiaScreen, which reportedly costs $1 per student. Administered by a classroom teacher, it identifies students as either “at risk” or “not at risk” for dyslexia.

The group also recommended piloting a second, more expensive screener at 10 of the 20 schools. The Predictive Assessment of Reading would be given to students who scored “at risk” on the Shaywitz screener at a cost of $7 per student. The goal would be to give classroom teachers more information about where at-risk students might need extra help.

Crucially, the Predictive Assessment of Reading is available in both English and Spanish, according to the working group’s report. That’s critical for Denver Public Schools, which is under a federal court order to provide equivalent curricular materials in both languages.

“The time for us to begin our dyslexia screener pilot is now,” wrote Holly Baker Hill, the facilitator of the working group and a special education instructional specialist for the district.

But 11 months later, the pilot has yet to begin. Parents and students are frustrated by the delay.

At a school board meeting last month, second-grader Forest Hansen said he’d been selling face masks sewn by his grandma to raise money so Denver could start the pilot. Forest has dyslexia, which he didn’t know until his family paid for private testing. With the help of outside tutoring, he’s doing well in school. Forest said he wants other kids to get help too.

“Dr. Hill, I think you are listening right now,” Forest said. “My mom will send this check to you.”

It was for $136.

District officials said they never abandoned the idea of a dyslexia screener. Frantum-Allen, Denver’s special education director, said the COVID-19 pandemic, which began just before the working group issued its recommendations, put the pilot project on hold.

“There’s no ill intent or anything we’re trying to cover up here,” he said. “We were trying to deal with the crisis priorities first and foremost.”

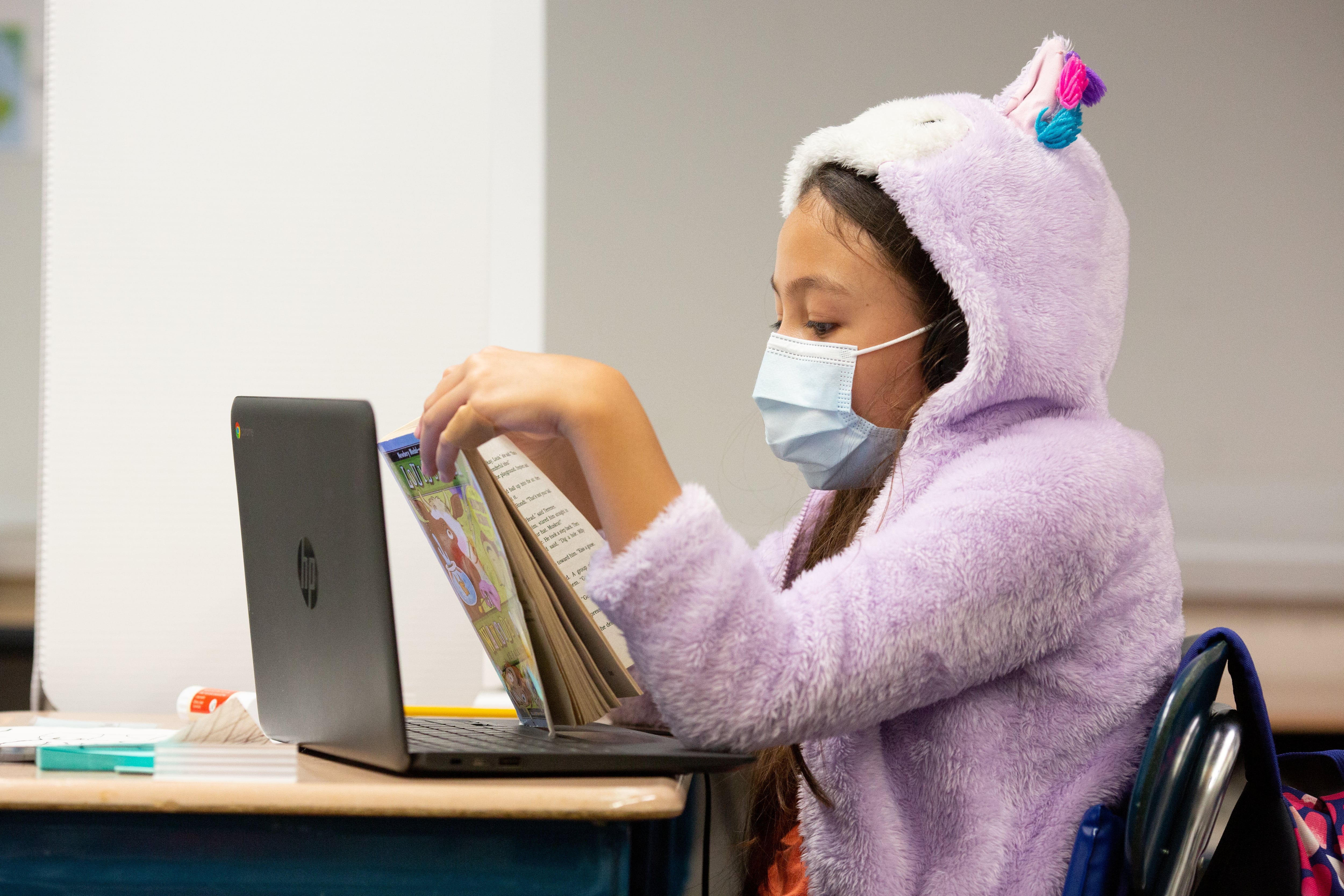

Now that teachers are being vaccinated and schools have reopened for in-person learning, Frantum-Allen said the district plans to resume the work related to the dyslexia screener, which he said will be part of a larger process to identify students with reading difficulties.

“I see this as a way of identifying, ‘What are the true needs?’ so we can help teachers address those true needs,” Frantum-Allen said.

A modest statewide test

In 2019, dyslexia advocates pushed for a state law authorizing statewide dyslexia screening for children with reading struggles, but ended up endorsing a more modest proposal for a five-school pilot program. It was supposed to start last fall, but was postponed. A new application window opened this winter, but with fewer applications than expected, the pilot’s future is up in the air.

If it goes forward as planned, kindergarten through third grade students at participating schools will be screened starting in the fall.

A University of Oregon group will lead the pilot, which in addition to screening children for dyslexia risk aims to bump up the quality of core reading instruction and intervention programming using a program developed by the university called ECRI — Enhanced Core Reading Instruction.

Nancy Nelson, a research professor at the University of Oregon who’s helping lead the pilot, said the goal is to ensure children are getting the right kind of reading instruction — explicit and systematic, with special help for struggling readers that aligns with whole-class lessons. The pilot will include lots of training for school staff, possibly starting later this spring.

“Screening doesn’t mean a child’s going to get special education,” Nelson said.

Still, the pilot’s format is meant to get kids much earlier access to specially tailored help rather than waiting until they’re desperately behind, she said.

The pilot includes a two-step screening system, with the first step relying on the Acadience reading assessment, which is already used by many Colorado schools to comply with the state’s reading law, the READ Act.

Students flagged by Acadience would get 30 minutes of extra instruction each day on foundational reading skills, with lessons previewing what will be covered the following day during whole-class reading lessons. Project leaders estimate 20% to 25% of students will fall into this group, but the proportion could be higher at some schools.

After two months, students who don’t make progress with the extra instruction would undergo a second screening, with information from various assessments and sources including family history of reading difficulty. School staff would intensify instruction for flagged students.

Those who still don’t respond will likely qualify for special education services, falling into a catchall category under federal law called “specific learning disability,” which includes dyslexia. (Schools don’t make dyslexia diagnoses, and an official diagnosis is not necessary for students to fall into the specific learning disability category.)

Nelson said about 5% to 10% of the school’s total K-3 students could end up qualifying for special education.

The state pilot will only include reading assessments in English. Nelson said the pilot’s protocols would require modification to work in Spanish or other languages, and while that’s an important step, her team first wants to demonstrate outcomes for students receiving instruction in English.

All kindergartners — eventually

The Boulder Valley district launched its dyslexia screening pilot last fall, screening 345 kindergarteners at 10 schools, including one charter school. District officials will screen a random sample of those children again this spring to determine if the timing of the screening during the year makes any difference. Until then, the district won’t release the number of students who showed up as “high-risk” for dyslexia characteristics on the screening.

“We’re still figuring out validity,” said Michelle Qazi, Boulder Valley’s director of reading, noting that parents weren’t notified last fall if their children fell into the high-risk category, but will be at the end of this school year.

For most students, Boulder’s pilot program uses a free assessment called the Mississippi Dyslexia Screener. Native Spanish speakers are screened with the Spanish-language version of a common reading test combined with a spelling test from a different assessment.

Qazi said students who score in the high-risk range on the dyslexia screener won’t automatically need special education services. The district already uses a high-quality phonics program — Fundations — for all early elementary students, she said. Knowing through the screening process which kindergartners have dyslexia traits will help teachers provide more intensive help to those who need it, she said.

“This is just one more piece of data that can help us lower the number of kids who fall through the cracks,” said Qazi.

Boulder’s three-year pilot will expand to 22 schools next year and to the rest of the district’s 37 elementary and K-8 schools the following year. Qazi said the district trained staff who normally administer vision and hearing screenings to conduct the dyslexia screenings last fall. Some screenings were done in person and some online. The district budgeted $102,000 for the pilot program.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect that Boulder Valley School District parents whose children fall in the high-risk category will be notified at the end of this school year, not at the beginning of next school year.