Following a tumultuous year, the Aurora school board is weighing whether to embrace a hands-on approach to managing the district or whether to defer to the superintendent, as their own guidelines say they should.

The upcoming vote, on June 1, stems from the latest instance of the board blocking the superintendent and his administration. The district wanted to start the process outlined in district policy for cutting staff, but the board said no.

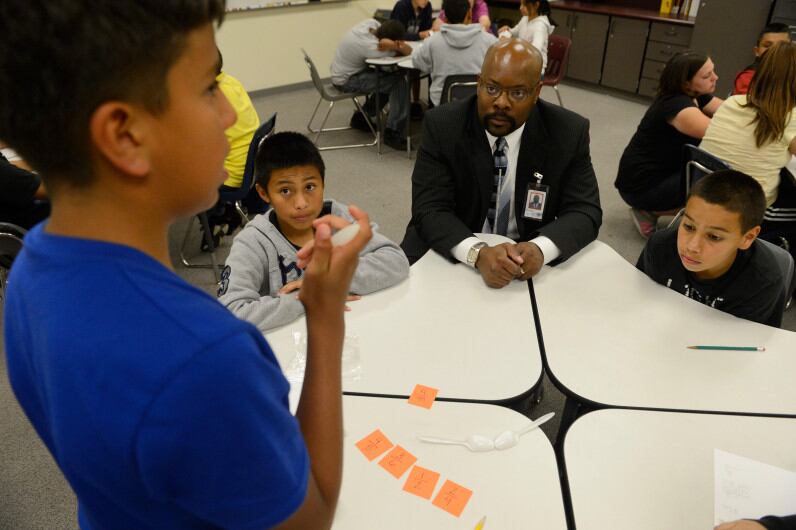

The board overseeing the fifth-largest district in Colorado has struggled for years to define its role with Superintendent Rico Munn. Munn’s contract has always stated that the board must follow what is known as a policy governance model. That means the superintendent makes decisions guided by board goals and policy. Approximately 30 Colorado school districts have this version of oversight, according to the Colorado Association of School Boards.

But the seven board members, a majority of whom were elected with help from the teachers union, have favored a more active role, despite a consultant’s urging that they stick to what they approved. Board members vary from being unapologetic about overriding Munn when they disagree with him, to wanting more clarity on the limits of their power. Some began questioning whether they serve only to rubber-stamp the district’s decisions.

A board decision next week on whether to do away with their current governance model and adopt one that allows a more active role would represent a major change to the board’s relationship with Munn and could have implications for his future.

In November, four of the seven board seats will be up for election. So far, none of those incumbents has announced if they will seek re-election. Board members say they want to clarify the board’s role for themselves and any new candidates before the election, so people know what to expect.

Consultant and trainer A.J. Crabill from the Council of the Great City Schools, who has worked with the board this school year, has warned that lack of clarity about the board’s role hurts the district.

“It is harmful to your organization’s ability to be effective, to say as a board ‘this is how we will function’ and then function in a materially different fashion than that,” Crabill said at a board meeting this month.

Aurora’s governance model was in place even prior to Munn becoming Aurora’s superintendent in 2013. Under this model, the superintendent makes decisions guided by board goals and policy. The Aurora board in addition has set limitations, to set guardrails on his work, such as not making major decisions without seeking community input.

“What you said is it’s my job, my responsibility, to sort through all the choices, make the best determination I can, and bring that to you,” Munn said, explaining his interpretation of the model. “You will then evaluate if it’s a reasonable interpretation of your policy — not whether you like it — but whether it’s a reasonable interpretation. And if it is, you will approve it.”

The explanation seemed to be new information to at least some board members, including Nichelle Ortiz, who said she didn’t like the pressure she felt to always go along with what’s presented. “I can’t stay with that plan if I’m always expected to just say yes,” she said.

This school year, the Aurora board reaffirmed its commitment to the model, adopting a new framework with new goals outlining the priorities board members wanted to focus on. That included goals around early literacy, postsecondary workforce readiness, and closing achievement gaps.

Those goals are also used to evaluate the work of the superintendent.

Munn and the district would not comment on the implications of a possible change in oversight.

Munn’s contract, which goes through 2023, states that “should the board elect to materially alter the governance policy, such changes may be deemed by the superintendent a unilateral termination by the district.” If that happens before June 30, that would trigger a severance payment of $180,000. Munn would have to provide a written notice 30 days prior to exercising that right, and the board and the superintendent must have discussions during that period to attempt to resolve concerns.

The board created a schedule to track progress toward the goals throughout the year. But those first conversations have been hampered by limited data, because the state and district halted many tests during remote learning.

At least twice this school year the board has argued about whether the district was straying from board goals.

In July the board overturned Munn’s plans to reopen school buildings.

After that, Munn tried to get the board to clarify who would make the next decision to reopen. But board members felt uncomfortable taking on the sole responsibility of deciding when it was safe to reopen, and struggled with what factors should be considered. They concluded the decision should be shared, but in November again reversed one of his reopening decisions.

More recently, when district staff sought approval to prepare for staff cuts, the board, in a split vote, refused and instead decided the district should not lay off any employees this year.

In response to board member complaints that the administration hadn’t considered other options, and that the board didn’t have other options, Munn earlier this month presented alternatives to layoffs. The board approved one that could cost the district up to $2.7 million.

Following that decision, board President Kayla Armstrong-Romero suggested that the board discuss how to administer a survey, including to administrative staff, about their perceptions of the board and their work. The board will take that up, and also when to release it and which groups to survey, on June 1.

Joshua Starr, a former schools superintendent, said that it’s common for boards to have trouble following a governance-type model for long. But he agreed not having clear roles is harmful.

“It makes an already difficult job that much more impossible,” said Starr, CEO of PDK International, a professional organization for educators. “I certainly would advocate for a governance model, but frankly clarity is what’s most important.”

Starr said the damage caused is not just to the superintendent’s work, but that it can have an impact on classrooms and on the community as well.

For example, he said, if a school board is swayed by political rhetoric such as the recent trend to police how teachers talk about race, a board might vote on banning certain books from schools.

Besides that decision having a direct impact on classrooms, it could also affect how free teachers feel to do their job, and how comfortable they are to raise issues with the administration or with their board.

For the public, seeing the fighting and not seeing progress on stated goals is what’s harmful, he said.

“Whenever people are fighting like this it decreases people’s confidence in the system, which means it becomes that much harder to make changes,” Starr said.

But all of this is also on the superintendent to fix, not just boards, Starr said.

“Part of the job of the superintendent is to make sure that the board, and the public for that matter, really understand each other’s roles and really spend time on it,” Starr said.