The statewide dyslexia screening pilot program authorized by a 2019 Colorado law will launch this summer with three schools — short of the five schools state officials originally envisioned.

The schools are Ignacio Elementary in southwestern Colorado, Singing Hills Elementary in Parker, and the Academy for Advanced and Creative Learning, a charter school for gifted students in Colorado Springs. The state education department released the names Monday and a department spokesman said a fourth school might be added later this week.

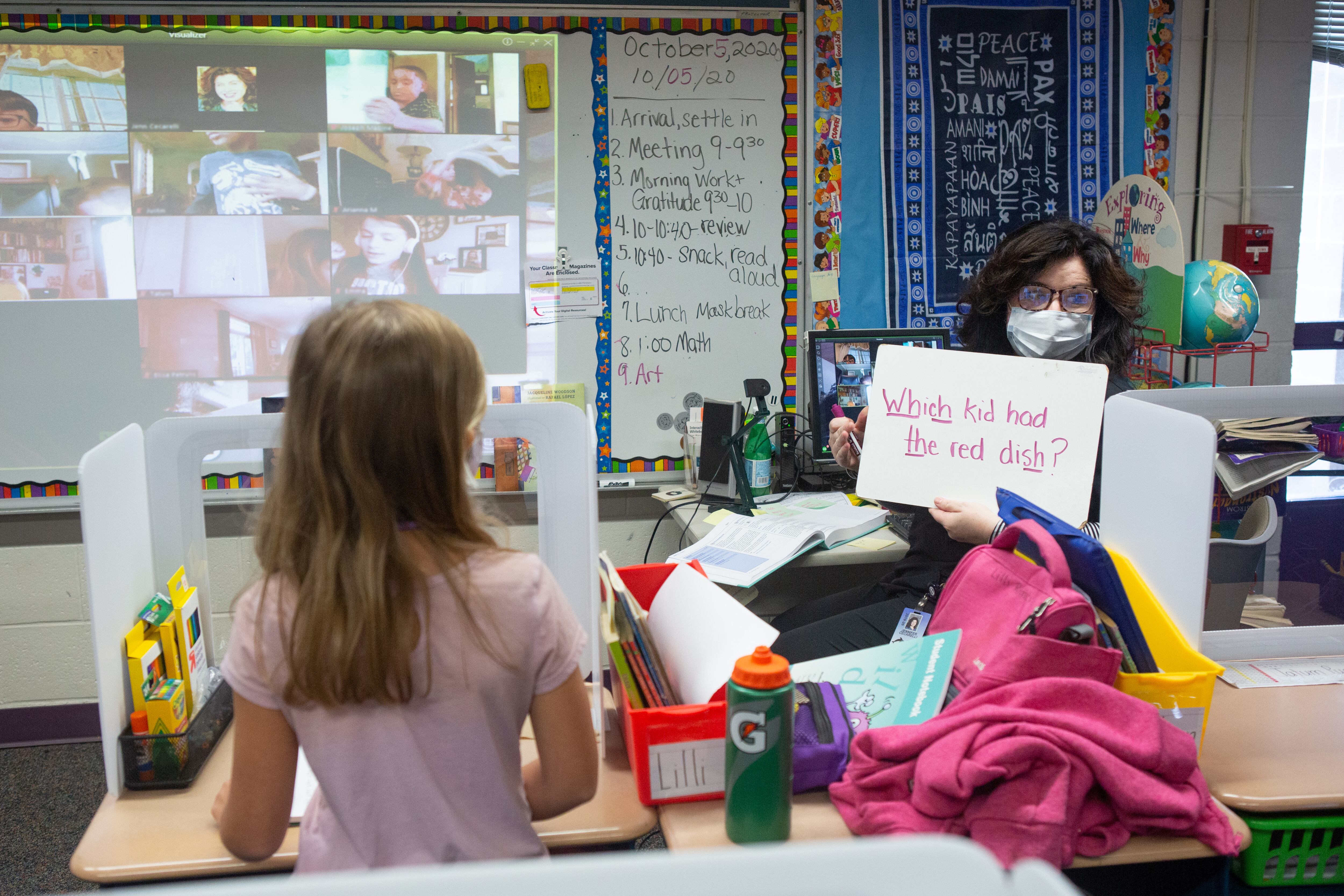

The pilot program comes amid ongoing state efforts to improve reading instruction and keep struggling readers from slipping through the cracks, but some advocates wonder how broadly applicable the results will be and whether the pilot will yield an approach that can be easily replicated.

“At this juncture, doing it in three schools, knowing one is a gifted and talented school, we really don’t want this pilot to go forward,” said Karin Johnson, a co-chair of the statewide dyslexia advocacy group COKID.

She said the group instead wants a universal statewide dyslexia screening program.

“We screen kids for vision and for hearing, and dyslexia is, to us, in that same category,” said Johnson, who is also a member of the state’s Dyslexia Working Group.

Dyslexia is a learning disability that affects about 15% to 20% of the population. People with dyslexia have difficulty identifying speech sounds, decoding words, and spelling them. Advocates hope that earlier identification of students with dyslexia will allow more students to get the help they need to become proficient readers.

Two large school districts have their own dyslexia screening programs in the works. The Boulder Valley district launched its three-year pilot last fall, screening 345 kindergarteners at 10 schools. The program will expand to 22 schools next year and to the rest of the district’s 37 elementary and K-8 schools the following year.

Denver district officials plan to launch a dyslexia screening pilot program in the fall. A district group recommended targeting young students at 20 elementary schools, but details have not been finalized.

Johnson said she appreciates the efforts in Denver and Boulder but believes a statewide screening mandate is necessary since district policies can change as leaders come and go.

“Tides shift,” she said. “There is a need for a framework to be built and expectations to be set when a new director of this or that comes in, or a new superintendent comes in.”

The state’s $92,000 dyslexia screening pilot was originally set to start this winter but only one school applied to participate, so the state education department delayed the launch. Four more schools applied during the second application window this winter, but not all of them met the requirements.

Floyd Cobb, executive director of teaching and learning at the Colorado Department of Education, said of the low applicant numbers, “I can only assume the impacts of managing school during the pandemic are pretty challenging and the thought of incorporating a new initiative in the middle of that might have proved to be too much for some.”

Asked whether three schools will provide enough data to determine whether the screening process was effective, he said, “Those are still answers that remain to be seen.”

A University of Oregon group will lead the state pilot, which in addition to screening children for dyslexia risk aims to bump up the quality of core reading instruction and intervention programming.