It’s hard to think positively about the pandemic, but for a tiny charter school in the foothills of Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo mountains, COVID helped spark a big change.

There’s now a school lunch program that serves about three-quarters of the school’s 80 students. Sometimes, even more on pizza days.

Last August’s lunch launch at Crestone Charter School came about with the help of COVID-era relief funds and close cooperation from the local school district in nearby Moffat. Staff there facilitate the lunch program, cook the daily meals, and transport the food 17 miles to the charter school in a specially equipped Ford Econoline van.

Christina Lakish, who has a second-grader and a fourth-grader at the charter school, said the lunch program has been a huge benefit to her family. She estimates it saves her $100 a month — money she’s been able to put into items like better winter boots for her kids.

Lakish’s 10-year-old son, a picky eater, wasn’t an instant convert to school meals after years of mom-packed lunches. It took a sit-down conversation about inflation and rising food costs to get him on board.

“I explained to him everything costs more money right now and I’m not making more money so we’re all taking hits for the team,” said Lakish, who is an emergency medical technician for the local ambulance service.

The school lunch program is free for all students at the charter school and the district’s single school because a large proportion come from low-income families. Saguache County, where Crestone and Moffat are located, has one of the highest child poverty rates in Colorado.

Thomas Cleary, the charter school’s director and previously a teacher at the school, said for years, the K-12 school chose to focus its spending on field trips and experiential learning opportunities to align with its educational focus. But some students were coming to school hungry.

“They weren’t able to learn and COVID exacerbated that,” he said.

The pandemic represented a “perfect storm in the positive sense,” providing the funding and a growing sense of urgency to feed students, Cleary said. It also came as school leaders were doing more to ensure equity and inclusiveness at the school. They didn’t want the lack of meals to be a deal-breaker for interested families.

Melanie Beckwith, the business manager for the Moffat Consolidated School District, said she’d long wanted to make lunch available to Crestone Charter students, but couldn’t get the finances to work. While the federal government subsidizes the cost of school lunches, districts must manage meal programs carefully because the margins are so thin.

Both Moffat Consolidated and the charter school kicked in part of the money for the new lunch program using federal COVID relief dollars for schools. The district spent about $27,000 to buy food serving and storage equipment, and modify the lunch van so food would stay at the proper temperature during the half-hour drive. The district also pays half the cost of the employee who delivers the lunches to the charter school and brings the dirty dishes back for washing.

The school, which donated an old van from its ski program for food transport, contributed about $35,000 this year — partly for the van driver’s salary and to pay an additional server.

School and district officials credit each other for a flexible partnership that has produced an increasingly popular lunch program. When the program started in August, about 40 students participated. Now, it’s up to 60 or more.

“So far everything’s just gone off just very, very well,” said Beckwith, who eventually hopes to add a breakfast program at the charter school.

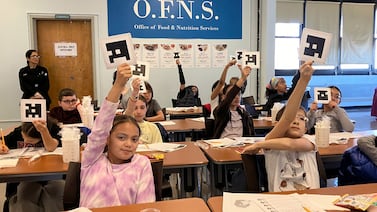

“When I have gone up there, the kids are so excited, they’re so appreciative, they’re so grateful,” she said. “That alone makes your heart soar.”

Of course, there have been a few bumps in the lunch program process. Once, when the regular van driver was out and Beckwith filled in, she quickly realized that a seat belt wasn’t enough to hold a large insulated container of chicken noodle soup in place on a hilly route with sharp turns. The soup spilled and Beckwith ended up shampooing the van’s seats.

Some charter school parents initially were nervous about their kids eating processed, non-organic, and non-local foods, or high-sugar items. Cleary said the school sends out lunch menus in advance so parents know what will be served, ensures vegetarian options are available, and provides white milk and almond milk, but not chocolate.

District Food Service Director Tina Serna and her team make a lot of the food from scratch, including lasagna, smothered burritos, and chicken stir fry. She also uses greens from the district school’s greenhouse to mix into salad.

Each week, Cleary sends surveys asking parents for input. While some still occasionally express concerns about the school lunches, he said, “In general, the kind of comments I’m getting are, ‘Thanks for feeding my kids.’”