Denver school board members soon will be faced with the often gut-wrenching — and politically unpopular — decision of whether to close schools. It’s a decision that a majority of the seven members have faced before as teachers, parents, and students.

But this time, they’re on the other side.

Denver’s enrollment is declining, and some schools have so few students, and so little per-pupil funding, that Superintendent Alex Marrero said the schools can no longer offer the robust programming students deserve. A committee has recommended Denver close elementary and middle schools with fewer than 215 students, as well as those with fewer than 275 students that expect to lose 8% to 10% more students in the next few years.

Marrero said he plans to make recommendations soon for which schools should be closed. The board is expected to vote on those recommendations next month.

But board members have expressed hesitation about closing schools. For some, that reluctance comes from their own experiences — which galvanized them to get more involved in district politics and eventually run for the board.

We spoke to four of the seven board members about their experiences and how that shaped how they think about school closure. Here’s what they said.

Carrie Olson

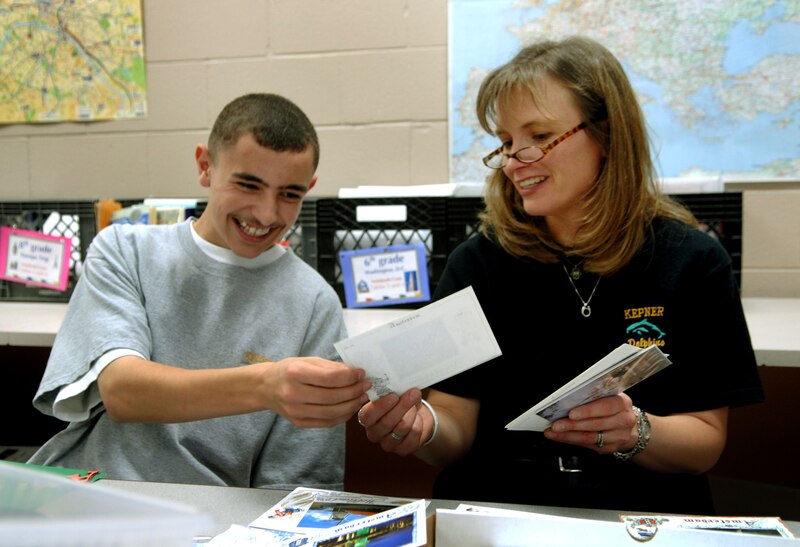

Olson was a teacher at Kepner Middle School in 2014 when the district announced it was closing the southwest Denver school due to low test scores.

“I didn’t feel seen or heard before the decision was made — or really, after,” she said.

Olson was a veteran educator, having started as a bilingual teacher in the district in 1985. She taught electives and literacy intervention at Kepner, working with a population where 60% of students were English language learners, 95% were Latino or Black, and nearly 100% qualified for subsidized school meals, an indicator of low family income.

In addition to teaching, Olson took students on educational trips to Washington, D.C., and Europe, life-changing experiences that became the subject of her doctoral dissertation.

Though Kepner students struggled with standardized tests, Olson said the school was more than its scores. She was shocked when district officials called a meeting to say they were “phasing out” Kepner — a euphemism for closure that meant the school would close one grade at a time — and phasing in other programs they hoped would do better.

Olson and some of her colleagues put together a proposal for a dual-language school that would celebrate students’ strengths and continue the educational trips. But the district rejected it. Instead, the school board chose a charter school and a new district-run school to take over.

“That whole competitive nature was so traumatizing to us,” Olson said. “We were all part of the community and so ingrained with the families and students.

“It felt like people downtown didn’t understand how this decision would fragment the community,” she said, referring to the decision makers at district headquarters.

The experience was one of several that pushed Olson to run for school board in 2017. She said she’s skeptical of school closures, and if the district is going to do it again, she wants the process to centralize the voices of students and families, and provide support to traumatized teachers beyond advice to do yoga and take bubble baths.

When she talks to her former colleagues about the closure, Olson said they often end up crying.

“The students felt like, ‘I’m not enough,’” Olson said. “Families would say, ‘We thought we had the best teachers in the city.’ I carry the students and the families and staff at Kepner in my heart always. I think about what was done to us and not with us.”

Michelle Quattlebaum

Quattlebaum’s family had a long history with Smiley Middle School by the time her youngest son was attending a decade ago. Her two older children had gone to Smiley, as had her husband.

In late 2012, the school board voted to phase out the northeast Denver school due to low test scores and lagging enrollment. But the enrollment was partly the district’s doing: Four years earlier, the board had co-located a charter school in the building, leaving Smiley with less space.

In 2013, the board made another controversial decision: To move the growing McAuliffe International School, which served a mostly white and affluent population, into the phasing-out Smiley, where most students were Black and Latino and from low-income families.

Quattlebaum fought against the Smiley closure, which she said families didn’t learn about until right before the vote. The process, she said, “didn’t feel good.” The one bright spot, she said, was when former school board member Happy Haynes came to talk to families.

“There were accusations thrown out, and her interaction was not to diminish or dismiss our very real feelings, but it was to actually listen to us,” Quattlebaum said. Had she not, Quattlebaum said, “the closure would have looked very different and felt even worse than it did.”

The district also helped the school throw a carnival, an event Smiley had held back when Quattlebaum’s husband was a student but which it couldn’t afford in recent years.

“It helped because tradition was being honored,” she said.

School closures didn’t galvanize Quattlebaum to run for a seat on the school board, which she won last year. But she said her first instinct is to oppose closures, even if she understands that may not always be realistic.

“If you have a school that normally provides services to 200 students and now only has 20 students, I’m that person saying, ‘Keep it open! Keep it open!’” she said. If that’s not possible, she said, “let’s try to come up with other alternatives to closing a school. What can that look like? I don’t know. But I understand the complexity of it.”

Quattlebaum’s own middle school, Gove, closed in 2005 and is now a parking lot.

“Every time I drive by there and somebody is in the car with me, I’m like, ‘That used to be my middle school!’” she said. “It impacts you.”

Auon’tai Anderson

Anderson’s experience with school closure was not as a parent or teacher, but as a student whose school was still grappling with a past closure and the threat of a new one.

Anderson attended Manual High School from 2015 to 2017, about a decade after the northeast Denver school with a proud history and a list of high-profile alumni was closed in 2006. The district reopened Manual a year later with a new leader and a new vision, but frequent changes made the next several years rockier than district leaders had hoped.

Anderson was drawn to Manual, where nearly all students are Black or Latino, by its JROTC program. He also became a student leader, and it was through that position that he learned the district was co-locating another McAuliffe middle school at Manual.

He and other student leaders met with school board members, including Haynes. He remembers asking why Manual students weren’t consulted about the co-location.

“I stood up and I asked, ‘Where was the student voice in this decision?’” he said.

Haynes, he said, answered by saying something like, “If you want to be on the school board, you can run and win like the rest of us.” Anderson said that motivated him to run for the board in 2017, when he was still a teenager. He lost that race but ran again in 2019 and won.

Anderson said he saw the move to co-locate a middle school at Manual — and other previous proposals to chip away at Manual’s space or programming — as threats to the school’s future. Students also couldn’t escape Manual’s past. On sports teams, he said, Manual students were taunted by other players who’d say things like, “At least my school didn’t close.”

Because of his experience, Anderson said he opposes school closures. He said he’s struggling with the prospect of having to vote on the superintendent’s recommendations.

“If I choose to run for re-election or a different political office, I don’t want to have the stain of a school closure on my record because I know how traumatic it is for families,” he said. “I recognize that enrollment is declining, but I haven’t given up hope that there’s another solution out there.”

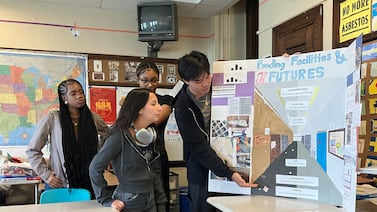

Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán

Fifteen years ago, when Gaytán’s oldest son was in fifth grade, she and her husband got a letter from the district. It said that their neighborhood middle school, Kunsmiller, where they were planning to send their son the following year, was closing.

Kunsmiller, where 88% of students were Hispanic and 93% qualified for subsidized meals, had low test scores, and the district was planning to transform it into an arts magnet school.

The letter came with a list of other middle schools that the fifth-graders could attend, Gaytán said. But none were near their southwest Denver neighborhood.

“It was so abrupt that it felt that parents and families were left scrambling to figure out what’s next,” Gaytán said. “It became one of those traumatic events that leaves families with shock and sadness for something you have no control over.”

Gaytán and her husband were both working, and they rearranged their schedules so they could drive their son across the city to Morey Middle School, where he made new lifelong friends. But Gaytán said it also robbed him of connections closer to home.

“You’re living a momentary trauma, but it also leaves aftereffects that break up communities and neighborhoods,” she said, “which left me questioning what was happening in Denver Public Schools and why decisions were made the way they were.”

The experience, Gaytán said, caused her to become more involved in Denver Public Schools and eventually run for a seat on the school board, which she won last year.

Gaytán said she’s open to the idea of consolidating schools with low enrollment to ensure all schools can offer robust programming. She’s concerned that some Denver elementary schools don’t have enough students to offer bilingual programming or hire full-time nurses.

But she said she wants the district to approach school closures differently than it has in the past — in a thoughtful way that takes families’ needs for transportation and mental health support into account, and “that will bring schools and communities together, not break them apart.”

“My hope is that because we have a board of individuals that have experienced this already, that we’re helping the district follow through in a very different way than how it was done back then.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.