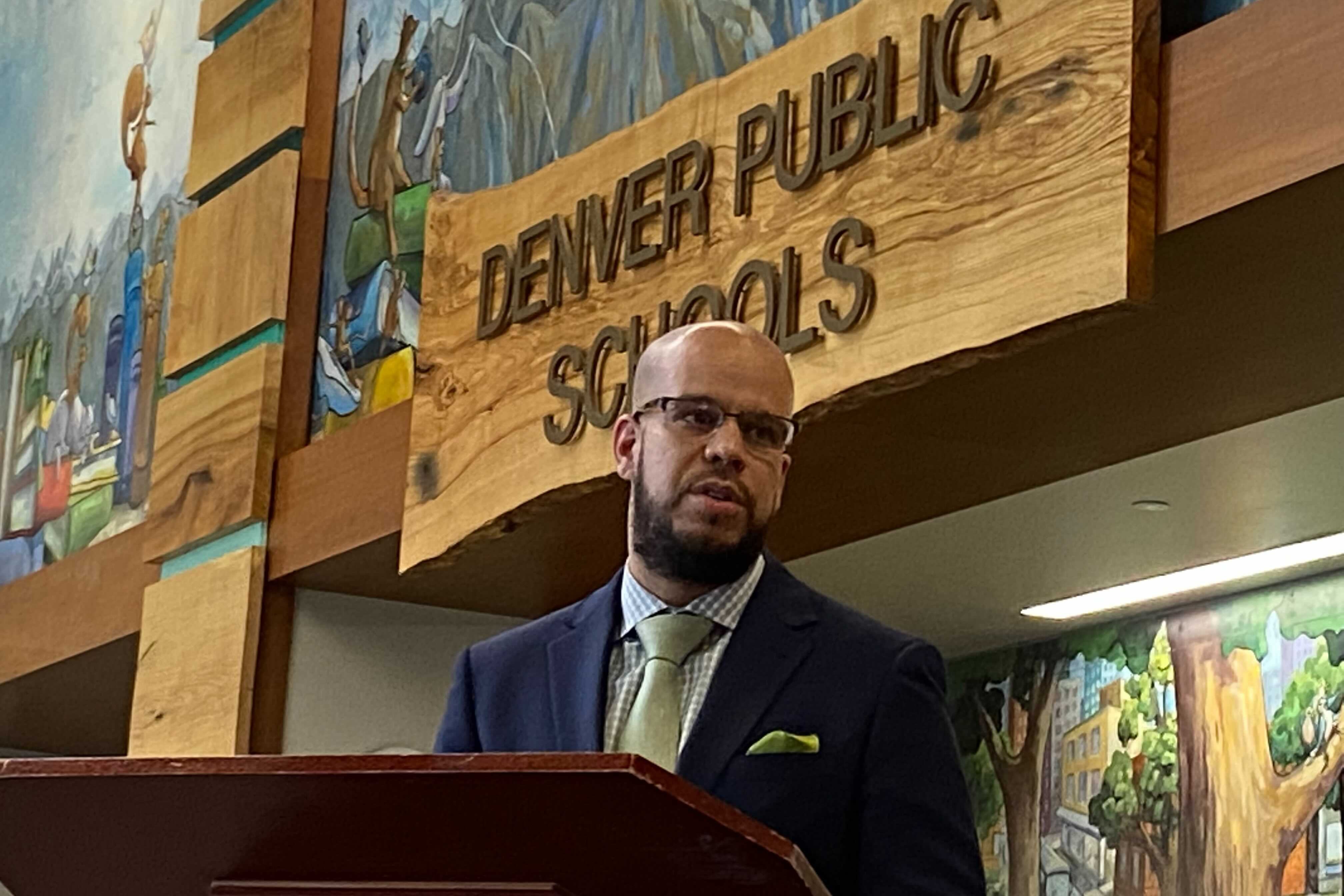

As part of his annual goals, Denver Public Schools Superintendent Alex Marrero has identified four “persistent and enduring systems of oppression” within the district to tackle.

Two of the systems are related to special education. The other two are related to the central office and the role of the school board, which hired Marrero last year.

Marrero’s goals for the year — which the school board will use later this month to evaluate him for the first time — called for him to identify two systems to dismantle. But he identified four systems instead.

The systems give an indication of how Marrero, who spent his entire career in New York before coming to Colorado, is approaching the superintendency in this state’s largest school district — including by undoing the way some things have been done for decades.

Now that he’s pinpointed what to change, Marrero said, “the next step is the ‘how.’” He said he intends to spend this school year coming up with detailed plans.

The first system he identified to dismantle was the target of a recent damning state investigation: “affective needs centers,” which are separate classrooms for students with emotional disabilities. The district has more than 30 such centers.

Black boys are assigned to the centers at disproportionately high rates. The state investigation found that the district sent Black boys to the centers without thoroughly evaluating them and then failed to monitor their progress while they were there, among other violations.

Although the district once called the centers “one of our most glaring examples of institutional racism,” Marrero said it won’t shutter them completely. District officials have said they can’t serve students with emotional disabilities without the centers. Instead, Marrero said, they will revamp the way students are placed there. The details will be laid out in a corrective action plan Denver Public Schools must submit to the education department by Monday.

“This has been a persistent and historical issue,” Marrero said of the problems with the centers. “This doesn’t happen overnight. This has been neglect over years and years.”

The second system Marrero identified to change is the one that oversees students who are entitled to accommodations under a section of federal disability law known as Section 504. Some examples of accommodations are preferential seating in the classroom, extended time on assignments, and the ability to take tests orally rather than written.

Last school year, 3,506 of Denver’s approximately 90,000 students — or about 4% — had Section 504 Plans that entitled them to accommodations. That’s fewer than the 10,806 students who had Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs, which entitle students to special education services such as therapy, counseling, and extra academic help.

But Marrero said there was only one 504 specialist at the district’s central office who oversaw the coordinators at each school — a ratio he said was shortchanging the program.

“We have to create more centralized support,” he said. “That was a glaring disparity.”

The third system Marrero identified was the district’s central office. Marrero announced in February that he was planning to shrink the size of the central office, which he had described as bloated. The aim of the cuts, Marrero said, was to reduce “redundancies and inefficiencies” and support a new way of sorting schools into groups — Montessori schools with other Montessori schools, for example — for the purposes of overseeing and supporting them.

Marrero made the cuts in May. They totaled 76 positions, including 15 executive-level jobs, freeing up $9 million, Marrero said. He reallocated that money to four initiatives, including raising the hourly pay for paraprofessionals to $20 this year.

Chalkbeat filed an open records request in May for a list of the 76 cut positions, but the district declined to release the records, citing a “work product” exemption. Chalkbeat repeated its request this week and was provided a list.

The cut positions range from part-time office assistants who were earning $8,700 a year to executives making as much as $147,000 and overseeing departments including community engagement and higher education initiatives, according to district documents. The median salary of the employees who were cut was about $77,000.

Chalkbeat also requested a list of the positions that Marrero added as part of the central office reorganization. But the district said “there are no documents that show added positions.”

The fourth system Marrero identified isn’t one to dismantle, exactly. Rather, it’s a system to strengthen in order to prevent the school board from “stepping into operations, which is catastrophic for a superintendent and district operations,” Marrero said.

Under the new system, called policy governance, the elected school board makes policies and the superintendent carries them out. The school board adopted policy governance in the spring of 2021 to help attract a new superintendent after Denver’s mayor and others accused the board of being dysfunctional and micromanaging the previous superintendent.

But the switch to policy governance has been rocky. To help, Marrero said, he hired a policy governance expert, Richard Charles, who has been advising the school board.

Policy governance is now part of Marrero’s contract. While he said it wasn’t what initially attracted him to apply for the top job in Denver, it helped seal the deal.

“What that told me is that, ‘We’re going to allow you to lead, but we’ll hold you accountable,’” Marrero said. “The blurred lines gets very difficult.

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.