Bedridden.

It’s not a common word in daily conversations, but one that’s important to know if you’re going to work in the nursing field. Through Community College of Denver classes, Japanese immigrant and English-learner Naoko Fujiwara, 38, is learning almost 10 to 20 such words a day.

The school’s approach differs from the English classes usually offered to immigrants. Instead of academic vocabulary, the college seeks to teach students English they need on the job.

With an accelerated and more practical curriculum, enrollment in the school’s non-credit English as a second language program grew phenomenally, from 50 to 400 students in two years.

Fujiwara was a nurse in Japan. Learning enough English to earn her nursing certification will open the door to a field desperate for workers.

She’s confident in skills from her past experience; she just needs the language. “If I can learn the medical terms in English,” she said, “maybe I can work.”

Jerry Kottom, who chairs the school’s English as a second language department, said he began to rethink the department’s role during the pandemic. Before, the school’s program would teach all students to read and write at an academic level.

“Our philosophy was everyone wants to go to college, right?” Kottom said.

But after several semesters, many students would lose interest. Kottom said he realized students wanted the English needed to earn a skills certificate or to communicate better with their managers.

So the Community College of Denver revamped its teaching, to try to enable students to quickly become fluent for their jobs while also learning the foundations of English.

Many students study at the college only briefly, before life circumstances intervene. That might include encountering financial difficulties or taking care of family here or in another country.

“They want jobs. They want better than the minimum wage,” Kottom said. “So we said, let’s get them there.”

The community program doesn’t offer college credit, like the college’s academic English as a second language program. The growth in the community program happened just by word of mouth, Kottom said.

He believes marketing the program will expand it even more.

The school’s classes range from beginner to more advanced ones like the one Fujiwara attends.

The program teaches workers in several industries, including a construction company, restaurant workers at Casa Bonita, and a laundry service company.

In one of the beginner classes, students who work at BrightView Landscape attend a class at the school’s north Denver campus. The landscaping company partnered with the school to teach its workers English so they can communicate better on the job and also to advance.

Kottom said employers join the program to improve communication between English- and Spanish-speaking staff, and to train workers for management or different jobs. With an acute shortage of workers, companies are eager to keep and improve their staff.

The Community College of Denver has sought to improve the quality of its instruction, hiring more masters-level instructors, especially for beginner classes.

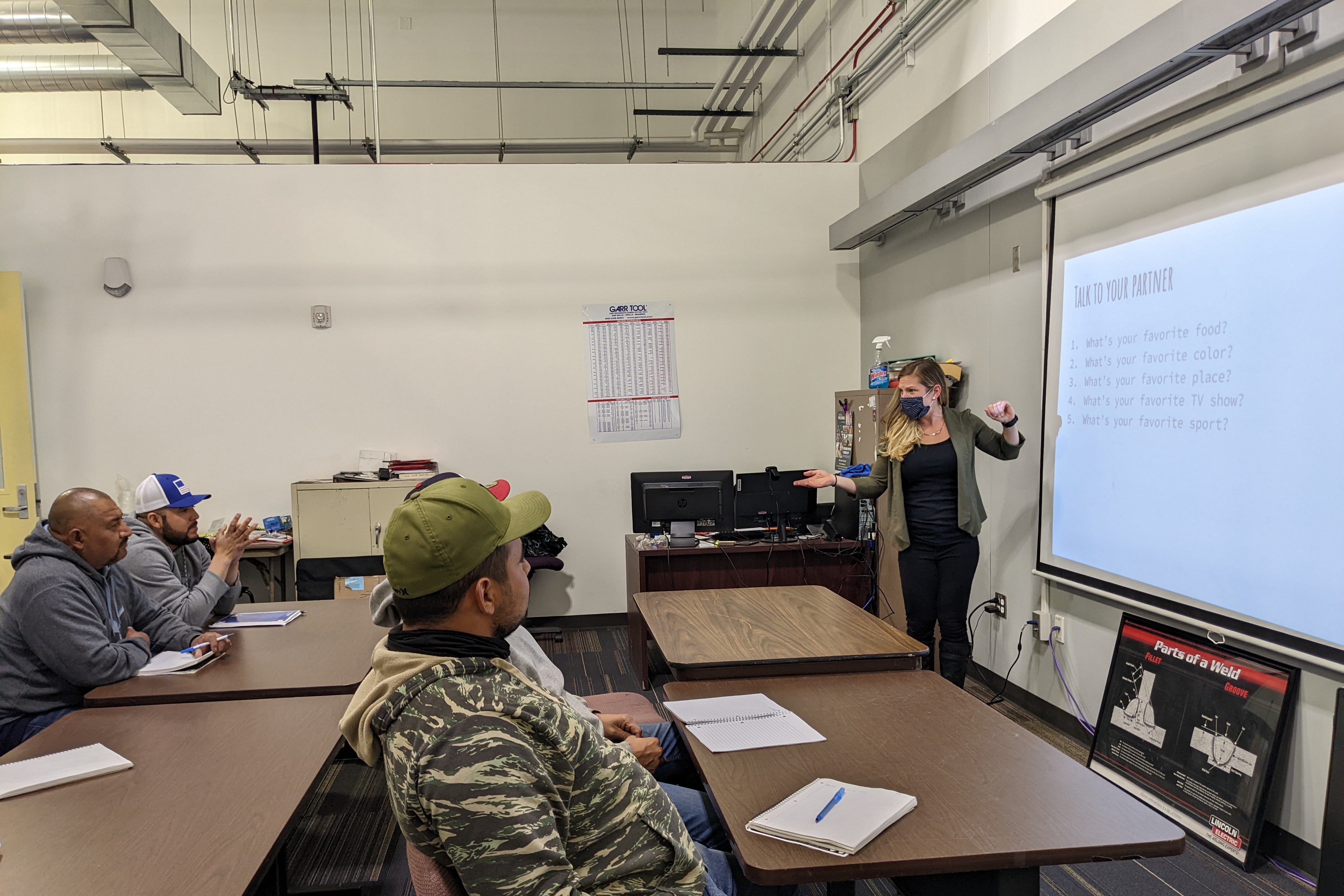

Darcie Sebesta, an ESL instructor, said she tries to keep the class light. Sebesta doesn’t keep attendance or hand out grades. But students take away lessons that they’re supposed to practice with their employers.

On a recent Tuesday evening, Sebesta guided the students as they talked in groups of twos and threes. Most of the students were still dressed in work gear from the day. Sebesta had students fill in the blank in sentences by using the pronouns his, hers, mine, and its.

Sebesta said she wants students to take away a love for learning. Because the students are at the most basic level, the class only minimally relates to work situations. She said she will build toward more job-related vocabulary.

“I don’t think we’re quite there yet,” she said. “But they have a lot of dedication to this for something that’s not really required.”

Fujiwara has a stronger grasp of English, and instructor Agnieszka Ramirez said learning the vocabulary of a nurse can be challenging. The school also provides English classes to students who want to get into early childhood education and manufacturing. School officials plan to add information technology classes.

Like Fujiwara, some are driven to get back into the medical field. Others are trying to find a way into the field, Ramirez said. All are highly motivated, and class often extends past the scheduled time.

“I am full of admiration for these students,” said Ramirez, who also learned English as an adult. “They’re incredible. But it’s also a lot of pressure. I always keep thinking what else could we do better? It’s a new program, and this is just the second semester of us doing it.”

The students put in extra time and effort to learn dozens of new words every week from the about 400 pages of the certified nursing assistant lesson book. An online platform called EnGen supplements class instruction.

Fujiwara said before the program she didn’t know where to turn to again pursue a career in the nursing field. After completing her nursing program and getting work experience, she would like eventually to become a registered nurse or licensed practical nurse.

“It’s my dream. I want to work again and I want to help people,” Fujiwara said. “But right now it’s a lot of the opposite — people are helping me. Hopefully someday I can give back.”

Jason Gonzales is a reporter covering higher education and the Colorado legislature. Chalkbeat Colorado partners with Open Campus on higher education coverage. Contact Jason at jgonzales@chalkbeat.org.