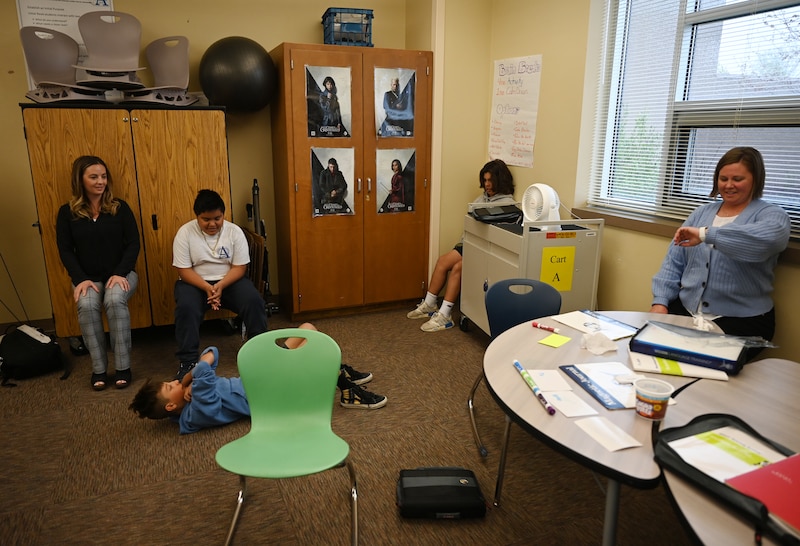

Kaylee, an eighth-grader in a light blue hoodie, read a list of words, one by one, to teacher Jessica Thurby. She stumbled on a few: Debate came out “deblate,” sacred turned into “secret,” and defend became “define.”

The pair went over the missed words. As Kaylee took another stab at “sacred,” she said, “It looked like the word “scared.”

“It did,” Thurby said. “So, our brain automatically guessed. We’re trying to get out of that, remember?”

For students who reach middle school without strong reading skills, these misread words turn into roadblocks that impede understanding and make it harder to learn. A new program at Alameda International Junior/Senior High School in Lakewood seeks to help.

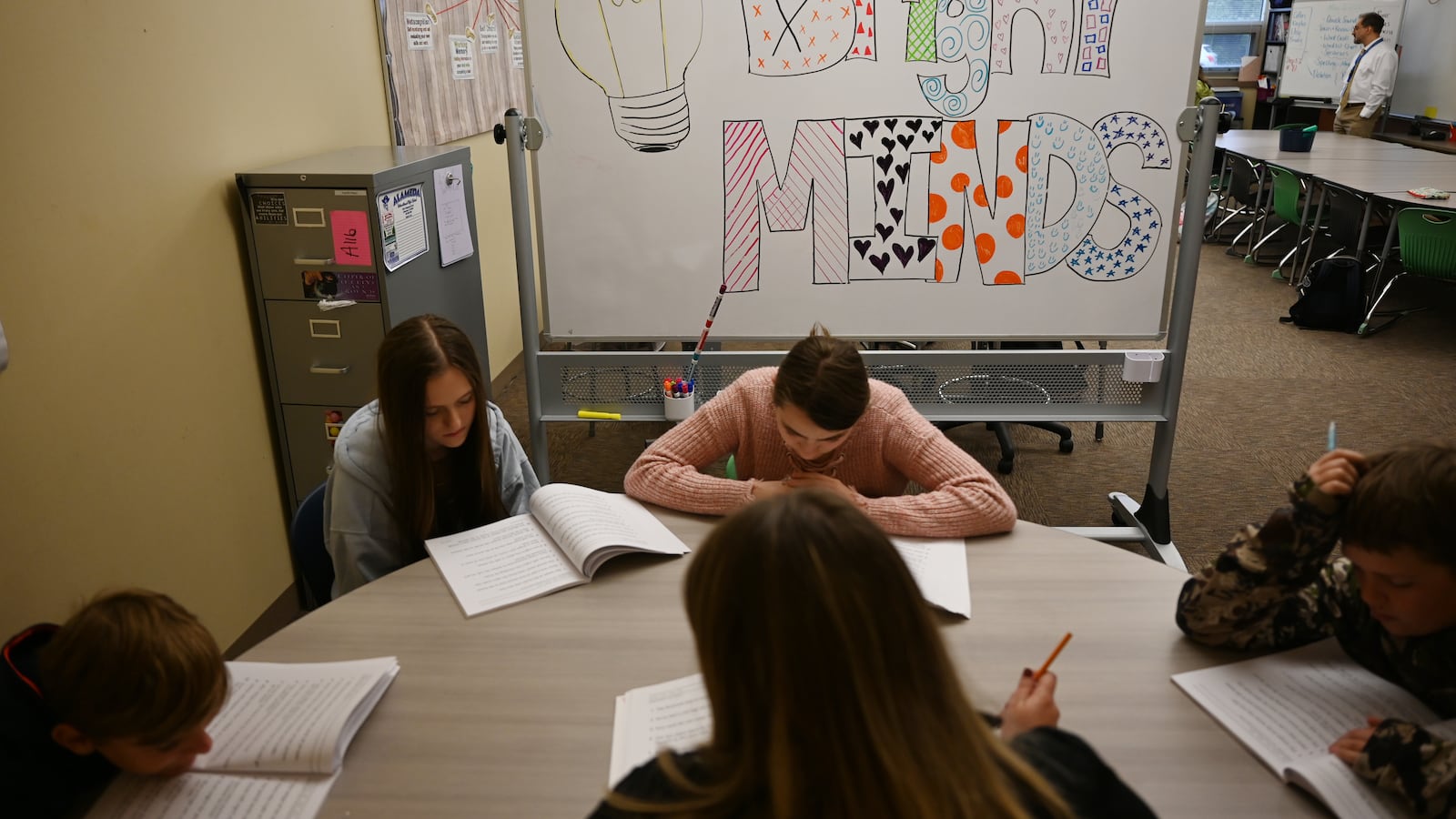

Launched last fall, Bright MINDS provides intensive reading help to 14 seventh and eighth graders with dyslexia or other reading challenges. School leaders plan to add a grade every year until Bright MINDS runs through 12th grade — with the ultimate hope that it will serve as a model for other schools in the 78,000-student Jeffco district and across the state.

Bright MINDS unfolds at a time when Colorado education leaders are keenly focused on improving early elementary reading instruction, with efforts including new training requirements for kindergarten through third grade teachers, and stricter guardrails on reading curriculum. But aside from a modest literacy grant program, state policymakers have given scant attention to the tens of thousands of secondary students who struggle with reading.

Students who can’t read proficiently face long-term consequences. They are at greater risk of dropping out, earning less as adults, and becoming involved in the criminal justice system.

Leaders at the state education department say their role in addressing older students who can’t read well is minimal because there’s no law equivalent to the 2012 READ Act, which mandates help for struggling young readers.

“Because there isn’t a statute similar to the READ Act, there is not a structure around literacy [in grades] four through 12,” said Floyd Cobb, executive director of teaching and learning at the Colorado Department of Education. “That responsibility is largely that of the districts.”

Experts say Colorado’s local control landscape means wide variation in the kinds of extra help provided to secondary struggling readers — if there’s any at all.

“We’re upfront with families about the fact that as kids move further in school, there often are less resources for the kind of intervention that is recommended,” said Laura Santerre-Lemmon, who heads the developmental neuropsychology clinic at the University of Denver, which frequently evaluates children for dyslexia.

Confidence killer

Dyslexia, a learning disability that affects 15% to 20% of the population, can be uniquely soul-crushing for students, making routine school tasks stressful and embarrassing.

In elementary school, Elise, a 13-year-old Bright MINDS student, stuttered when she read aloud and was called stupid by other kids because she was a slow reader and poor speller.

The seventh grader, who has trouble hearing the sounds that make up words, remembers finally memorizing the word “people” because her teacher got so frustrated with her.

“I memorized a lot of words that way because I was scared of her getting mad at me,” she said.

Even after students are identified with dyslexia, problems can persist when they don’t get the right kind of help. Brody, a Bright MINDS student, was diagnosed with dyslexia and qualified for special education services in fifth grade. But his mother Kristina Trudeau said he still wasn’t making progress at his Adams County school.

He was reading at a kindergarten level, recognizing only basic words like “cat” and “dog.” At one point, she discovered the reading program Brody’s teachers were using wasn’t recommended for students with dyslexia.

Trudeau has seen the real-life impact of Brody’s reading difficulties. One night, she found him crying alone in the laundry room. He’d planned to fix himself dinner, but couldn’t read the directions on a package of potstickers.

“It just broke my heart,” said Trudeau. “He thinks differently. He learns differently. He deserves to have those needs met.”

How big is the problem?

A dearth of data makes it hard to quantify how many middle and high school students struggle with reading in Colorado.

More than half of Colorado’s middle school students scored below proficient on state literacy tests in 2019, the most recent year that sixth, seventh, and eighth graders took the test. It’s a blunt measure, however, in part because the state doesn’t separate reading and writing results.

The scope of reading problems is clearer for younger students because Colorado’s 2012 reading law requires schools to identify students with significant reading deficits in kindergarten through third grade and spell out plans to help them catch up. The state has a pot of money earmarked to help this group.

There’s no such requirement — nor funding — for students in fourth grade through 12th grade, though some students stay on their so-called READ Plans far beyond third grade. About 48,000 Colorado students in fourth through 12th grade were on the plans in 2021, about 8% of students in those grades.

But many students with reading struggles are never flagged for the reading plans because their problems aren’t severe enough in the early grades or they mask weaknesses with advanced vocabulary, well-developed verbal skills, or other compensation strategies. Such students often manage to muddle through school with passing grades even if they’re missing a lot of what they read.

That’s what happened to Collin, a lacrosse-loving seventh grader who lives in the Jeffco district and is enrolled in the Bright MINDS program.

His mother Leslie Dennis said up through second grade Collin could take reading tests using a tool that read text passages to him. Her son always did well on the tests, but in third grade he had to read the passages himself and his scores plummeted. Collin didn’t get a READ Plan though, just pullout sessions to help with fluency — the ability to read with speed, accuracy, and appropriate expression.

It wasn’t enough. Collin got average grades throughout elementary school, but still stumbled over words, hated reading aloud, and called himself “dumb.”

Dennis knew there was a bigger problem, but said, “I couldn’t pinpoint what it was.”

Finally, in fifth grade, on the advice of another mom, she got her son privately tested and found out he had dyslexia.

Equity and access

Bright MINDs — the second half of which stands for Multisensory Intensive Dyslexia Support — was the brainchild of Jeffco’s former Superintendent Jason Glass, said Todd Ognibene, Alameda’s school psychologist and the Bright MINDS coordinator. Other administrators forged ahead with the plan after Glass left in 2020.

“I was jumping for joy that this was finally something that the district … recognized the need for,” said Ognibene.

Alameda, where nearly three-quarters of students qualify for subsidized meals, was chosen to house the program because of its central location. Ognibene and the school’s Assistant Principal Andrea Arguello designed Bright MINDS with Thurby, a special education teacher, and Sarah Richards, an English as a second language teacher whose daughter has dyslexia.

To ensure accessibility, they don’t require a dyslexia diagnosis, which can cost hundreds of dollars to obtain through private testing. Instead, the team screens applicants from Jeffco and other Denver metro districts for characteristics of dyslexia or related reading problems.

Finding a structured dyslexia program inside a public school is a welcome surprise for many families. Private schools with similar services are pricey.

Some parents tell Ognibene, “This was more difficult than finding a needle in a haystack.”

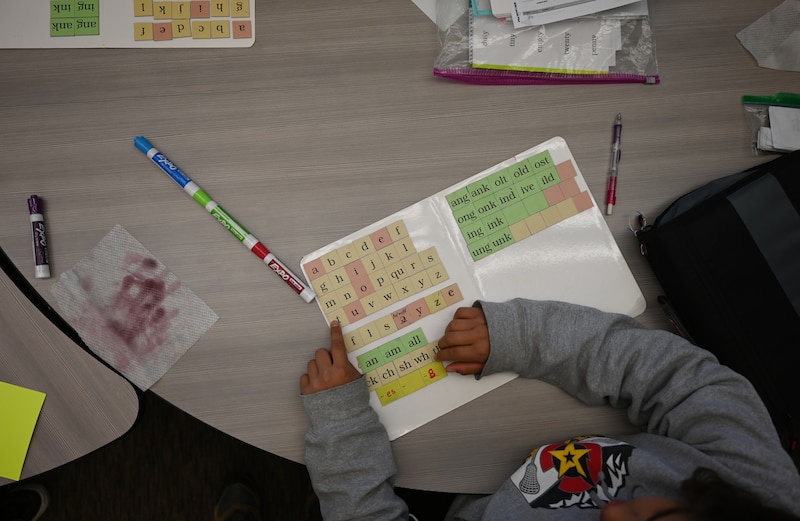

Students in the program get 80 minutes a day of reading instruction. About half get the most intensive help, using a state-approved intervention program called Wilson Reading System. The other half, whose reading skills are somewhat stronger, use “Just Words,” another Wilson program.

Bright MINDS is still in its infancy, but early results are promising. From fall to winter, participating students made 68% more growth in reading than would typically be expected.

“I’m thankful … It’s exactly what I’ve been fighting for,” said Trudeau, Brody’s mom. “You shouldn’t be going in debt $30,000 a year just so your kid can have an appropriate education.”

This year, Bright MINDS includes some students on special education plans, some on other kinds of learning plans, and others with no plan at all. A few students speak English as a second language.

Students in the program also get help with skills like planning and organization — since conditions such as attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder often co-occur with dyslexia.

Bright MINDS students don’t miss core classes to attend their daily reading class. Instead, they take one less elective block. In addition, Thurby or Richards joins them in core classes to ensure they’re getting the help they need to absorb the content.

Arguello, who has dyslexia herself, recalled the impact of being pulled out of general education classes for reading help when she was in school.

“It took me a long time to get caught back up,” she said.

Shifting attention

There are signs that more help is on the way for struggling readers in higher grades.

In 2020, the federal government awarded Colorado $16 million for grants to districts for literacy efforts spanning early childhood through high school. Ten districts have received the grants so far, including Aurora, Cherry Creek, St. Vrain Valley, Harrison, Lewis-Palmer and Sheridan.

In addition, a bill set to be signed into law this spring will require elementary principals and reading interventionists who work with fourth- through 12-grade students to complete training on reading instruction similar to what is already required for K-3 teachers.

Jill Youngren, a consultant helping the St. Vrain Valley and Sheridan districts with their literacy grants, advocates a systemic approach to helping older struggling readers — ensuring educators give the right assessments, identify the root problem, and know how to provide gap-closing instruction.

“If you catch them early you prevent all that, but we can’t give up on a kid who didn’t have the right kind of instruction and say, too bad, so sad.”

Bright MINDS students and their parents say the program has helped with more than reading, spelling, and writing this year. It’s made the experience of having dyslexia less isolating.

“It’s been amazing,” said Elise, “It’s kind of like having a bunch of siblings and like an extra set of parents that are watching over you.”

A quick survey of career goals among Bright MINDS students runs the gamut: Astronomer, doctor, game warden, engineer, and baseball player. Ognibene said empowering students to reach their goals is a priority.

“We want them to graduate from Alameda knowing that there’s essentially no postsecondary option that they can’t pursue,” he said.

Having trouble viewing this survey? Go here.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.