When students get to middle and high school without strong reading skills, the results can be devastating.

In response to a recent Chalkbeat survey, dozens of parents and educators described secondary students who refuse to read out loud for fear of being teased, who can’t understand math word problems or science vocabulary, and gradually give up on school altogether. They worried such students face poor job prospects and bleak futures.

One mother called the distress faced by older struggling readers “astronomical.”

But respondents also had lots of ideas for helping older struggling readers. It’s an area ripe for attention, since most states and districts have focused recent reading improvement on early elementary students.

Their ideas included dyslexia screenings, tutoring, and more training for middle and high school teachers. Several parents and teachers recommended specific intervention programs — with names like Wilson or Barton.

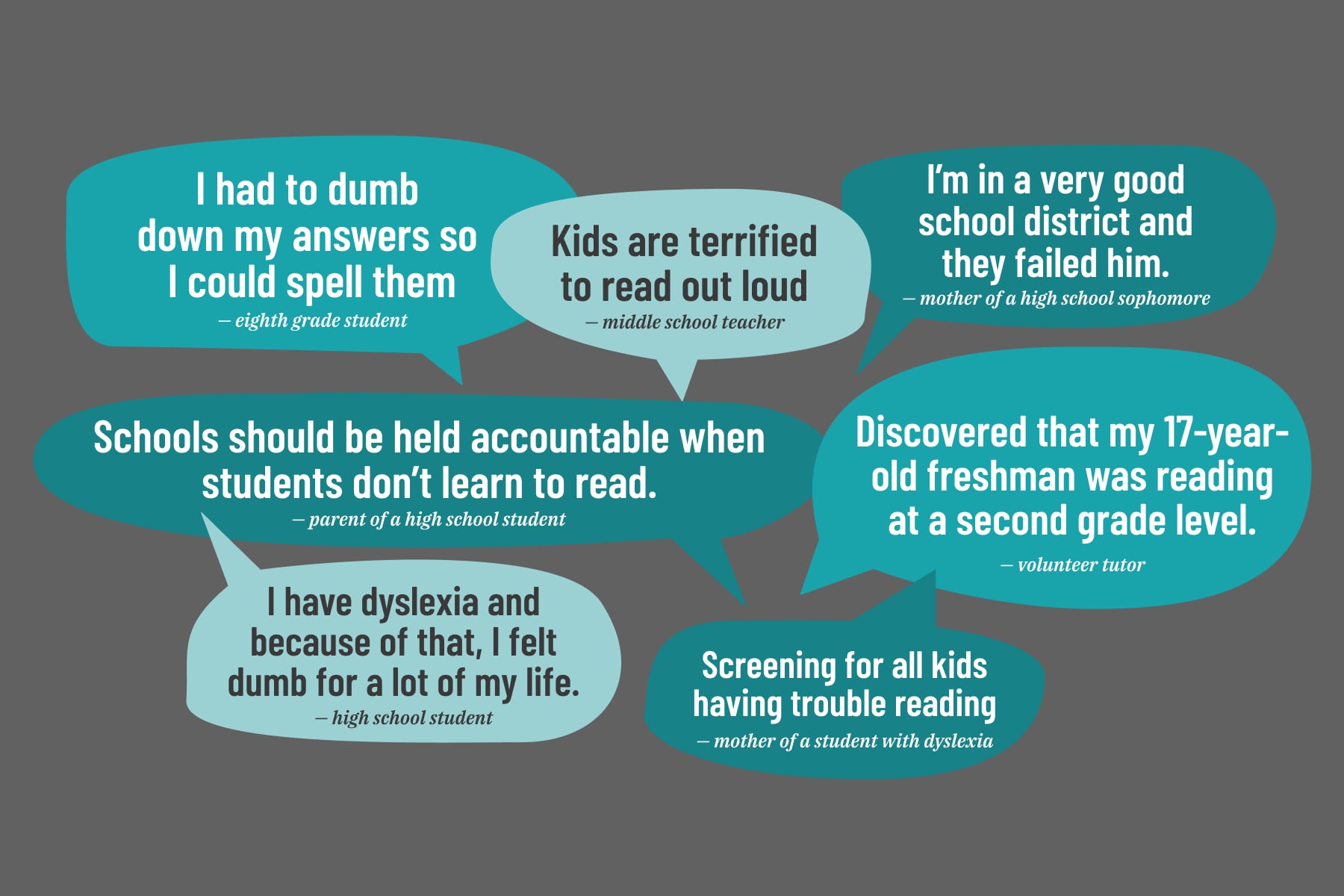

Here’s a selection of responses from students, parents, and teachers across the country.

The impact of reading struggles: shame and stress

“I have dyslexia and because of that, I felt dumb for a lot of my life. It really affected my mental state as I felt lesser than a lot of my peers because I couldn’t read as fast and spell as well as them. In middle school, I wanted to hide my dyslexia because I wanted to feel like I fit in and was as smart as all my friends.” — Audrey Drakos, high school student, Littleton Public Schools, Centennial, Colorado

“When I mentioned my work to help our brilliant daughter who has struggled with dyslexia and dysgraphia, the stories of pain and anxiety that poured out of my students broke my heart!” — Diane Doucette-Cooney, recently retired special education instructional aide (high school), Kodiak Island Borough School District, Kodiak, Alaska

“I provide reading intervention for sixth through eighth grade students. All of the students I serve did not know all letter sounds and struggled to read single syllable words at the beginning of the year. These are general education students, not students with special education plans. Their behaviors in the classroom are often disruptive because they cannot access the content. Additionally, because they have experienced years of academic failure, their self esteem is extremely low, so I’ve built a social-emotional component into my intervention classes.” — Kellyn Sirach, teacher, Jefferson Middle School, Champaign Unit 4 School District, Champaign, Illinois

“I observe the effects of limited reading skills on a daily basis. Kids lack self confidence, they can’t access the reading content assigned in their core classes, they turn to other avenues for affirmation, usually social media and behaviors that distract from their academic struggles.” — Shawna Hettich, teacher, Bear Creek K-8 School, Lakewood, Colorado

“My daughter falls further behind every year. Schools should be held accountable when students don’t learn to read. As long as there is no accountability, schools will continue to ignore student needs.” — Beth Moore, mother of a high school student, Annandale, Virginia

“I discovered that the 17-year-old freshman I worked with was reading at a second grade level. Though it took a while, I was able to arrange for testing which showed she had dyslexia. I was able to enlist help from BOCES [Board of Cooperative Educational Services], got her a tutor and other support, but she did not participate. I think she’d already given up on school after so many years without success.” — Carolyn Faselt, CASA Truancy Volunteer, Clear Creek County, Colorado

Ideas for change: screening, training, funding

“They need to screen every student for dyslexia, not just the kindergartners. We have 12 grades in the system currently that are unscreened. Once screened, we’ve got to arm parents with the knowledge of what to do, and ideally provide some resources to support kids OUT of school.” — Sarah Wise, parent of a Boulder Valley school district student, Boulder, Colorado

“As a district, we have a long way to go in building teacher knowledge in regard to literacy, but my school is making great strides to support students with dyslexia and reading difficulties. My building administrators are fabulous and allow me to provide training in how to support all students, especially those who struggle with reading in middle school.” — Kellyn Sirach, teacher, Jefferson Middle School, Champaign Unit 4 School District, Champaign, Illinois

“We need research-based reading curriculum. We need to use these curriculums in middle and high school to get kids moving, not just ignore it in the name of teaching grade-level standards that kids aren’t going to get anyway.” — Tessa McAleer, teacher, STRIVE Prep — Lake campus, Denver, Colorado

“All teachers need to be trained in evidenced-based literacy instruction. Schools need to have access to Orton Gillingham-based intervention at all grade levels.” — Gina Bring, parent of a middle school student, Blaine, Washington

“Students need to know that they are NOT stupid. Students need effective instruction to develop their phonemic awareness and phonology skills. If they did not receive this instruction earlier, no wonder they cannot read well. Students need counseling — one-on-one and group — to relieve their feelings of inadequacy and shame, and to understand what they need and what they can accomplish.” — Diane Doucette-Cooney, recently retired special education instructional aide (high school), Kodiak Island Borough School District, Kodiak, Alaska

“Funding is essential for the training teachers need to work with struggling students. I have been continually frustrated by the lack of money needed to train staff, simply because the students are past third grade.” — Shawna Hettich, teacher, Bear Creek K-8 School, Lakewood, Colorado

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.