A new state law will require about 5,800 Colorado elementary schools and child care centers to test their drinking water for lead and install filters or do repairs if they find elevated levels.

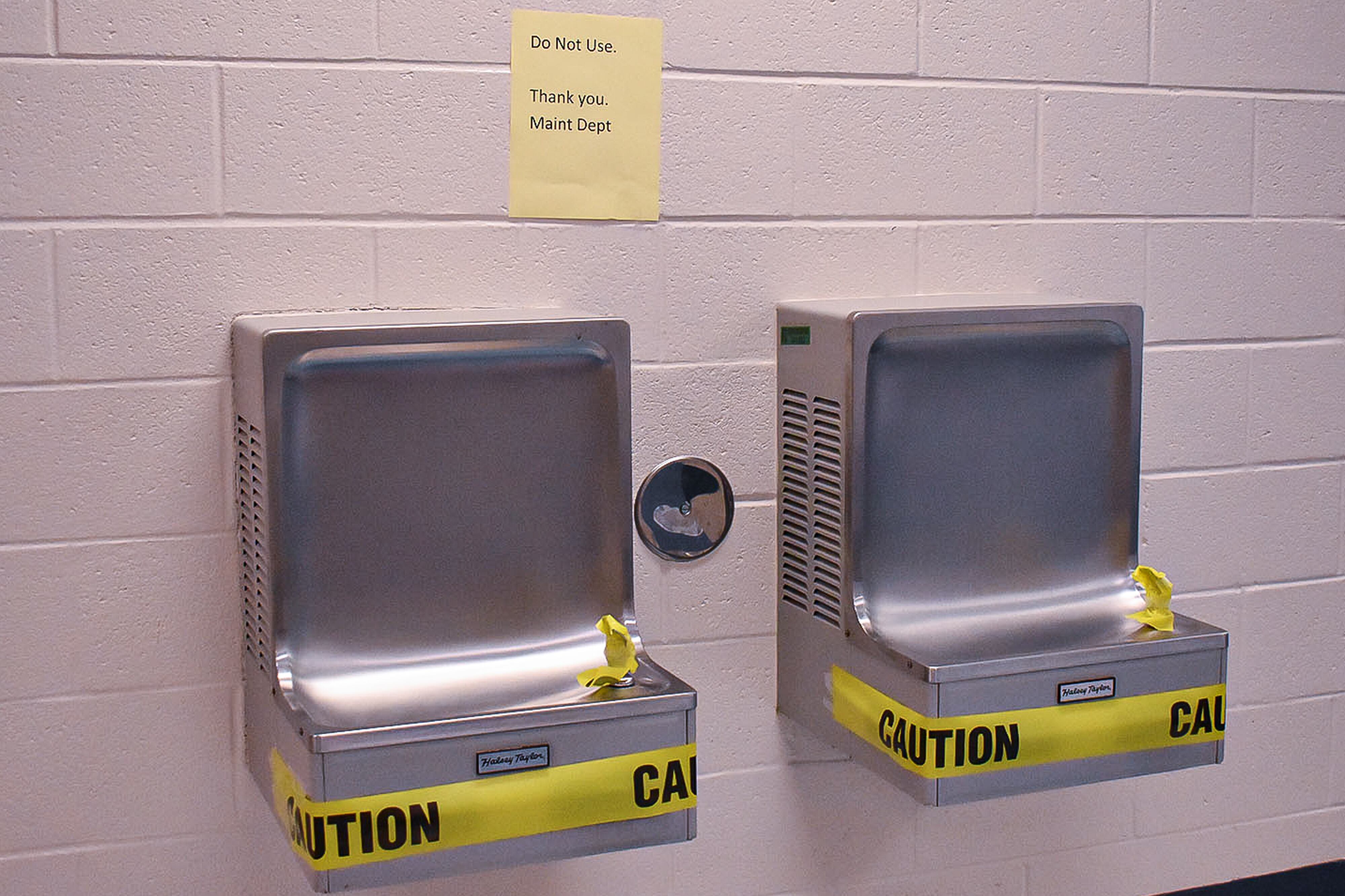

Schools and child care facilities will have until May 31 to test their water and will have to make fixes if lead levels are 5 parts per billion or higher. That threshold is the same as the limit set by the federal government for bottled water but lower than what most Colorado school districts previously used.

The law, which comes with $21 million for testing and repairs, represents the first time Colorado has established regulations governing lead levels in school and child care drinking water. It comes as a growing number of states have passed laws to address childhood lead exposure following the 2014 water crisis in Flint, Michigan.

Lead is a harmful neurotoxin that can cause learning disabilities and behavior problems, with even low levels of exposure impacting a child’s IQ. Lead levels in American children have decreased dramatically since the 1970s, but studies show many children still have detectable levels.

A 2021 study published in the peer-reviewed journal JAMA Pediatrics found that 72% of Colorado children under 6 who were tested had detectable levels of lead in their blood — though many young children in the state are never tested at all.

Generally, Colorado lawmakers, school officials, and advocates praised the new law for taking steps toward ensuring students have safe drinking water at school or child care, though for some, it didn’t go as far as they’d hoped.

Jaquikeyah Fields, communications director at the Colorado People’s Alliance, a racial justice group that helped shape the bill, described the law as a big accomplishment that could serve as a stepping stone to future legislation on the topic.

“I think that the goal was to do more with it,” she said, but it’s ”still pretty solid.”

Bob Lawson, executive director for facilities management and construction in the 15,000-student Pueblo School District 60, said he’s pleased the law establishes a clear lead threshold for school water.

“At least they’ve done something to create a standard for us to use,” he said. “That’s the big thing because Colorado didn’t have anything.”

Elin Betanzo, a water scientist who helped uncover the Flint crisis, said legislation to ensure safer drinking water in schools is a good thing, but that installing filters right away is a better strategy than testing water sources and then making fixes. She said it’s well known that school drinking water often contains detectable levels of lead.

In part that’s because plumbing advertised as “lead free” is still allowed to contain a small amount of lead.

“Water is a universal solvent. When water’s in contact with lead, the lead gets into the water,” said Betanzo, founder of the Detroit consulting firm Safe Water Engineering.

“It might not be today, it might not be tomorrow … If the lead is present, it’s going to be in your water at some point.”

Evolving legislation

Colorado’s new lead law changed significantly from its introduction in part because of pushback from some school and early childhood leaders. The final version contains fewer and less stringent requirements than were in early drafts.

In its original form, the bill would have required schools and child care programs to install filters on all drinking water sources, install a filtered bottle-filling station for every 100 children, and conduct annual testing of lead levels in drinking water. Fixes, plus new signage and other notification, would have been required for all water sources with lead levels of 1 part per billion or higher.

The 1 part per billion threshold is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for school water fountains, but few states have adopted it. Instead, most with recent laws on lead levels set the limit at 5 or 10 parts per billion. Maine’s threshold is 4 parts per billion.

Groups representing child care providers initially opposed the bill, saying the proposed rules would have been onerous and cost prohibitive.

Dawn Alexander, executive director of the Early Childhood Education Association of Colorado, said it would be unfair to hold child care facilities to such strict standards, when many cases of lead poisoning originate in children’s homes, which are not subject to such rules. During her time in a previous job at the Weld County health department, she found that investigators usually traced high lead levels to lead paint in a child’s residence.

“It just doesn’t make sense to have these … impositions on businesses that are already struggling when it’s not really the source that’s generating such extreme health issues in the children in our state.”

Alexander said she was pleased with the final version of the bill: “They really did bring it to a much more reasonable approach.”

Licensed home-based child care providers will be able to opt out of the new requirements.

Mark Anderson, a pediatrician at Denver Health, thinks the law is a good one, especially because it comes with money to help schools and child care centers cover the cost of testing and repairs.

“If cost isn’t a concern I can’t think of a good reason not to get the lead out of the water,” he said.

But Anderson noted that water isn’t the main source of high lead levels in Colorado children.

“You’d have to drink a lot of water to get a lot of exposure if it was 15 [parts per billion] or below,” he said.

Anderson, who is part of a regional network of experts on children’s environmental health, said most often high lead levels in children stem from exposure to lead paint, lead paint dust, or a category he called “imports,” which can include cookware, spices, or candy from other countries.

Researchers have found that children living in ZIP codes with predominantly Black or Hispanic populations are more likely to have detectable lead levels than children living in ZIP codes with predominantly white residents.

Post-Flint school efforts

In the wake of the Flint water crisis, some Colorado school districts began voluntarily testing school water and making fixes when lead levels hit or exceeded 15 parts per billion — the level used at that time by the Environmental Protection Agency to trigger action by water utilities.

Starting in 2017, some Colorado districts took advantage of a voluntary state grant program that paid for lead-testing in schools, but the program didn’t cover repair costs and wasn’t widely used.

Officials in the Denver school district, Colorado’s largest, began testing water in 2016 using the 15 parts per billion standard, switching to a 10 parts per billion threshold in 2019. Over the last six years, the district replaced 264 plumbing fixtures, and installed 83 water fountain filters.

But the new law will require additional work because previous testing found about 150 drinking fountains with lead levels above the new threshold but below the old one.

Joni Rix, the district’s environmental program manager, said even though some of those fountains are in middle and high schools, which aren’t the focus of the new law, the district will install filters on them.

The fixes, she said, will cost “a good chunk of money” — about $1,000 each for initial filter installation and $70 for annual maintenance.

State Rep. Emily Sirota, a Denver Democrat and one of the legislation’s sponsors, said lawmakers used higher-end estimates in allocating one-time COVID recovery money for the new law. State health officials said they hope that will cover as much of the testing and remediation costs as possible, but details have yet to be worked out.

In the Pueblo 60 district, five schools will get fixes this month to comply with the new 5 parts per billion threshold. While district officials tested all water sources districtwide in 2017 and 2018, they used a 10 parts per billion threshold to determine where to make fixes.

Officials in the Mesa County Valley district in western Colorado made fixes at five of 42 schools after participating in the voluntary state grant program a few years ago. Aside from the buildings where new fittings or bottler fillers were installed, no schools had lead levels higher than the newly established 5 parts per billion limit.

The district has since built two new schools, but hasn’t received guidance from state health officials about whether lead testing is required.

“If they want us to test those sites we’d be more than glad to, but I don’t see any reason why we’d have to do that,” said Eddie Mort, the district’s maintenance coordinator.

A spokeswoman for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, which will oversee implementation of the new law, said no decision has been made about whether schools or child care facilities that have tested their water in recent years will have to conduct a new series of tests.

“The final approach may not be a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution for all schools across the state that previously tested,” she said by email.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.