Decorating cookies with constellations, talking with scientists on biweekly video calls, and visiting a local nursery to select plants for an outdoor classroom.

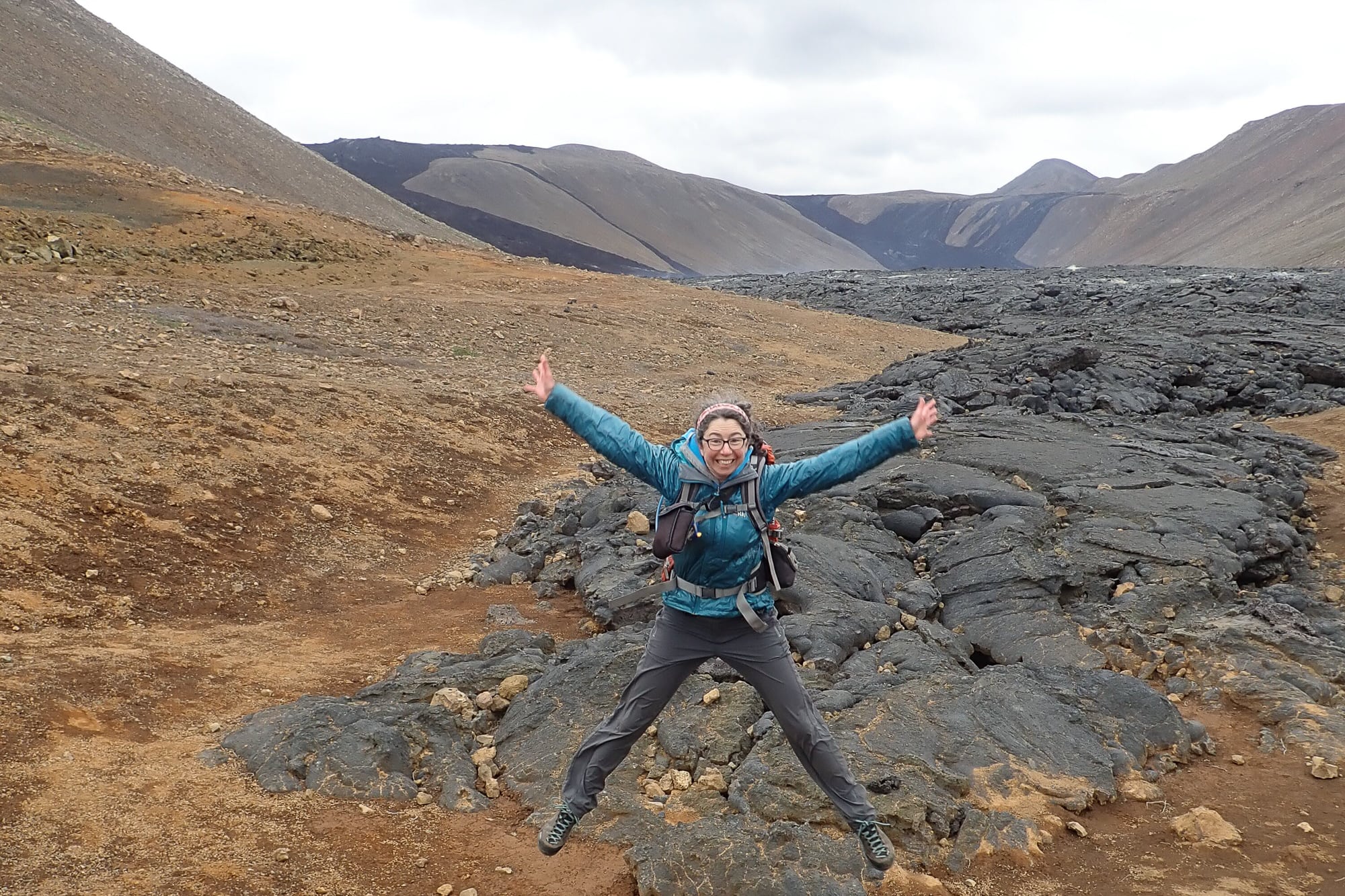

These are just a few of the activities Stacy Wolff does with students as a science resource teacher at Flagstaff Academy, a charter school in Longmont. Part of her goal is to create memorable hands-on science lessons that engage kids the way churning butter, studying pond life, and practicing bird calls enriched her own school experience.

Wolff’s lessons don’t unfold during class time alone though. Five years ago, she helped form a club called the Green Team after students came to her with concerns about Flagstaff’s recycling program. Since then, she said, the group “has transformed our school,” revamping the recycling program and launching an effort to reduce food waste in the lunchroom, among other things.

Wolff was one of two teachers recently named an Outstanding Environmental Educator by the Colorado Alliance for Environmental Education. She talked to Chalkbeat about how she teaches students about planetary orbits, what question launched the school’s “Marsketeers” club, and why she changed her approach to science fair projects.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

There wasn’t as much of a moment when I decided to become a teacher, but a movement over time. My love of animals, nature, and science took hold when I was a young girl so it seemed to be a logical next step to obtain a degree in wildlife conservation.

After graduation, I alternated between avian research, science education, and outdoor education positions. While I loved all of my work, I wanted to focus on science education: inspiring students to become lifelong learners, better understand the natural world, engage in their community, and get excited about science.

How did your own school experience influence your approach to teaching?

My most memorable experiences in school were hands-on and inquiry based. I remember learning about phase changes of matter by making butter from scratch in second grade, doing a pond study in the forest adjacent to my middle school, and going on field trips for geology and ecology class in high school. In college, I learned the most — and had the most fun — from labs and field research. I fondly remember listening to tapes of bird calls in the library and then the satisfaction of identifying them in the wild.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

My favorite astronomy lesson was developed by Mike Zawaski and Cherilynn Morrow. In the Kinesthetic Astronomy lesson, students create a scale model of the Earth and sun, and learn about the motions of the Earth in relation to the sun. Students take on the role of being Earth, and once students learn how to rotate and orbit around a model sun, they can then learn to answer many astronomy questions using their bodies. They can discover answers to questions like, “Why does the full moon rise at sunset?” “Why do we see different stars at different times of year?” and “Why does the sun rise in the east and set in the west?”

You helped create a food rescue table in the cafeteria. How does it work?

The food rescue table was created to reduce food waste and address food insecurity in our school community. Our Green Team students and staff advisers worked with district lunch personnel to be certain we are following USDA guidelines and collaborated with our paraprofessionals to decide how to best collect food during lunch periods..

If a student finishes their lunch, they can ask permission to visit the food rescue table and if there is food or drink available, that student can take it. At the end of the lunch period, students add certain leftovers from the school lunch to the table. These foods include whole fruit and unopened items like milk, yogurt, cheese sticks, cookies and juice. Our amazing district lunch staff checks the temperature in a cooler throughout the day. At the end of the last lunch period, the bins get placed on a shelf so that students can access leftovers for snacks that afternoon and the following morning.

Tell us about the Green Team and the Marsketeers Club at your school.

Five years ago, three students asked to meet after noticing recycling was not being disposed of properly. They wanted to create a solution to this problem so we formed The Green Team. This student-led group has transformed our school. Through guidance from our district’s school wellness coordinator and Eco-Cycle, plus grants from the Colorado Department of Education and our Parent-Teacher Organization, we created the food rescue table, revamped our recycling program, and built an outdoor classroom.

The Marsketeers Club began after a fifth grade student asked me during our astronomy unit why he couldn’t view Mars at that time. I asked the student how he might figure it out. After brainstorming a number of possibilities he decided to ask a scientist. After that conversation, we created the Marsketeers Club to help students learn about Mars, the search for life, and how scientists learn to ask good questions. Each biweekly Zoom meeting is facilitated by myself and Dr. Mike Zawaski, a scientist with the Mars 2020 mission and Texas A&M University. We begin each meeting with a presentation by Dr. Zawaski or another scientist friend of his. We focus on recent Mars discoveries or other exciting Earth and space science missions, and then the 15 to 20 students ask questions.

What is something happening in the community that impacts your students?

Something that is always happening in the community is change. Kids frequently come to me with stories of new discoveries and questions about their world. One of our big topics in second grade is monarch butterflies and their journey through Colorado. Students have made the connection that every action can have a positive or negative impact and that there can be many perspectives to any given situation, such as the decision to use pesticides. Our students have begun to realize they can conserve monarch butterflies by planting milkweed seeds and other flowering plants for all the life stages of the monarch, and this, in turn, will help create a balanced ecosystem for our human and non-human communities.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

When I began my teaching career at Flagstaff Academy, students in third through fifth grade participated in a science, technology, engineering and math fair. I inherited the traditional way of facilitating the program in which students chose a topic and completed their project at home. After my first year of teaching, I realized that this approach created stress for students and their families. I surveyed my students and created a focus group of parents and our principal, confirming my prediction that students did not feel prepared to conduct an entire experiment themselves and that many parents did a lot of the work.

As a result, I revamped the STEM fair to include classroom activities where students planned and potentially began their experiments. I provided guidance, used graphic organizers, and a timeline of milestones. From this, students had the background to do more of the work themselves, get input from their peers, and the confidence to successfully complete their project.

What are you reading for enjoyment?

“Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard,” by Douglas Tallamy, and “A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds,” by Scott Weidensaul.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.