A divided board. A mistrustful public. Lagging academic achievement. Rising youth violence.

The Aurora school board is searching for a new superintendent, who will face these issues and more.

“It’s the superintendent who sets that tone and builds that team and drives that momentum,” said Aurora school board President Debbie Gerkin. “So what’s at stake is whether we get a leader who can do that or one who can’t.”

Aurora’s next superintendent will be the district’s first new leader in nearly a decade. That person will have to navigate a feuding board, restore trust with the community, and get buy-in for their vision. At the same time, the ideal candidate would figure out how to meet the needs of a diverse student body, improve mental health services and academic performance, and find a fair way to deal with school closures and shifting enrollment.

A look at recent years shows how challenging the job is. Superintendent Rico Munn abruptly announced in December that he’d leave at the end of the school year, and stepped into the background while the board named an interim leader.

Board members declined to speak on reasons for Munn’s departure and about whether they want a change in course for his long-term projects. Recent disagreements in public meetings included anger over school closures and a lack of trust in efforts to engage the community.

School board members are interviewing six unnamed semi-finalists from among 28 applicants and are expected to announce three finalists as soon as next week.

The search profile describes an ideal candidate as having a background in education, something that the previous superintendent didn’t have, and a track record working with diverse communities and in a large school district.

An immediate challenge would be navigating dynamics of a divided board, which could change in the fall, when three of seven members are up for election.

A divided board splits on priorities

How the school board relates to its next superintendent will affect how much trust people feel in the district.

For a superintendent to be effective, they need clear guidance from the board. But the school board has struggled to agree on how the superintendent should manage the district.

A report on the community’s views of the district named board governance as one of the district’s main challenges.

“Comments included that the Board does not appear to understand their role and the governance model, can be ineffective in their communication, unfocused, and have appeared divisive and not aligned on priorities resulting in the appearance to work against each other and district leadership,” the report presented earlier this month said.

Board members have not contradicted the finding. In an interview, Gerkin said that it didn’t come as a shock.

“It is hard to see it in writing of course, but not a surprise,” she said.

She said that the board is committed to addressing their challenges and is united in understanding the importance of selecting the next superintendent.

“We’re seven different individuals, and every one of us is passionate about kids and passionate about education,” she said. “Different people with different ideas and lots of passion don’t always agree on how to put that together.”

Linnea Reed-Ellis, president of the teachers union, said she thought “productive disagreement” among the board members was OK. The board majority often has voiced similar criticisms of the district to those of the union, particularly in discussions about the facilities plan Blueprint APS and certain pandemic-era measures.

The report also mentioned a lack of trust across the organization, which search firm associate Scott Siegfried speculated was driven by issues with the Blueprint APS.

Reed-Ellis framed the issue as “a lack of clarity in vision as to what we are pursuing as a district.”

Whether or not the district’s next leader and the board want to change course, they still will face the same issue of changing enrollment patterns.

Aurora enrollment has fallen as families flee the western parts of the district closest to Denver, where rents and home values are rising faster than family incomes, and as lower birth rates contribute to fewer students. However, new developments out east are attracting more families with children. The demographics of the two sides differ. Munn wanted to make changes equitable, to avoid putting the new schools only in the east and closing campuses only in the west.

Gerkin said that ensuring that the Blueprint changes are implemented transparently and equitably will be a critical task for the new superintendent.

“We definitely don’t want the east side of town to be all new and shiny and older parts of the district to just look old and uninviting,” she said. “It depends on what the buildings look like, what kind of resources you’re putting into the buildings, all those things are important for the next superintendent to be working on.”

Achievement has risen in Aurora

Munn’s administration boosted student achievement. Graduation rates rose, expulsions dropped, and the gap in graduation rates of students of color and their white peers narrowed. Together, those gains lifted Aurora off the state’s watchlist for low performance.

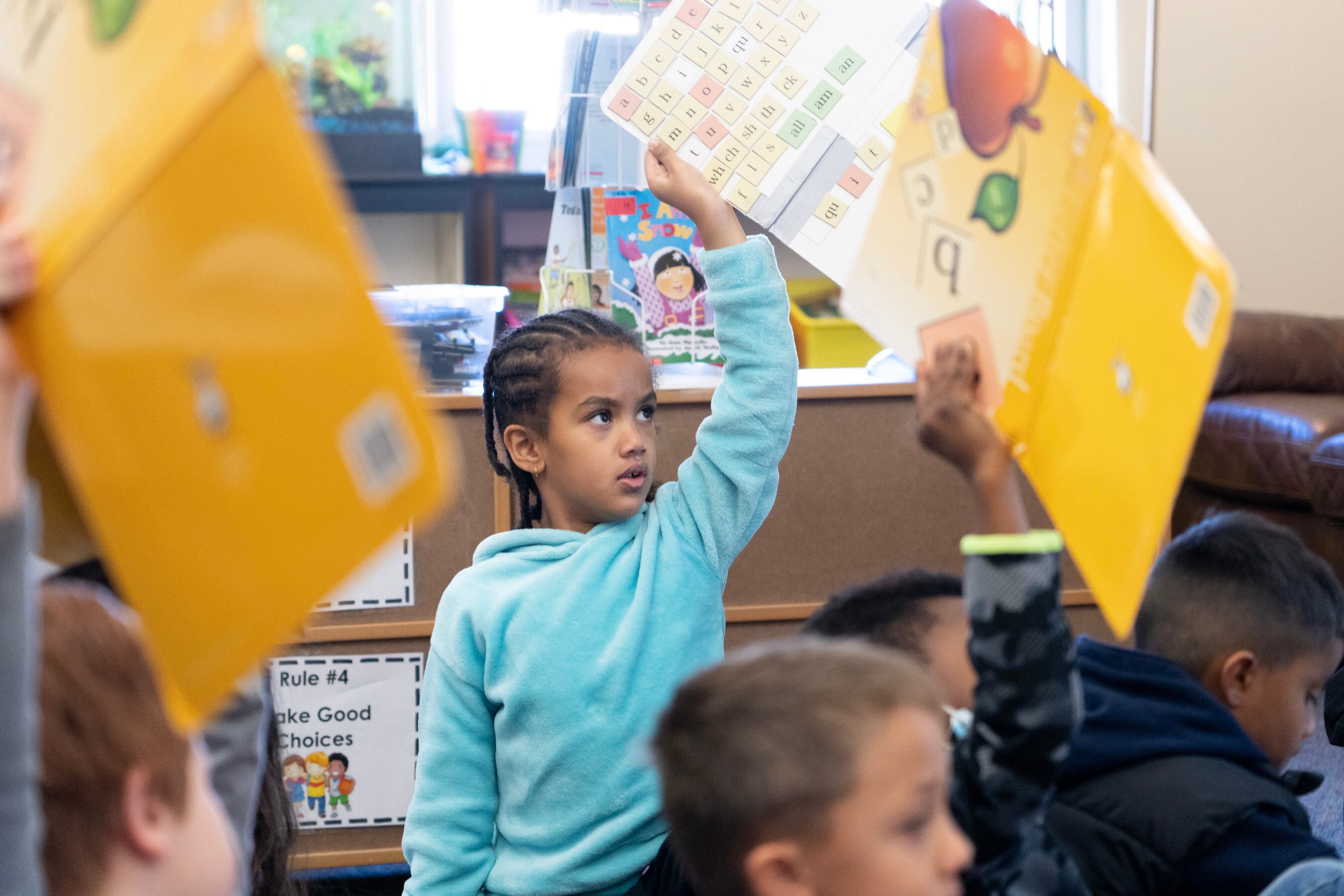

Still, some schools have struggled to raise academic achievement. Student engagement plummeted when the pandemic forced students to learn remotely. And now, academic achievement at those schools still lags.

That worries Mordecai Brownlee, president of the Community College of Aurora and a parent in the school district.

To boost opportunities for Aurora graduates, the community college partners with Aurora schools on concurrent enrollment — where students earn college credit for classes taken in high school — and plans for a new program in construction management on the college’s CentreTech campus.

“You’ve certainly got to look at the amount of students who are failing to achieve a credential of higher education once they leave APS,” Brownlee said. “We owe it to this community to figure that out together.”

The school board set goals to close achievement gaps and accelerate learning but set them aside two years ago to focus on the emotional and social needs of children.

Munn worried that would hurt school ratings once the state’s accountability system returned in full force. In Colorado’s system, schools that have five years of low ratings face state-mandated improvement plans that could include closure. This past year’s ratings were meant to only give the public an indication of where academics stand and don’t move schools closer to outside intervention. But if Aurora schools score similarly this year, many more may be on a path toward state intervention.

For schools with multiple years of low ratings, Munn’s approach was to create district plans to turn them around before the state stepped in. He succeeded in preempting state-ordered plans. That approach is one of many things that may change with new district leadership.

Reed-Ellis said she hopes that the new superintendent will be willing to see students “holistically” and investigate other ways to measure learning and growth besides standardized testing.

“We all know our students are more than a test score,” she said.

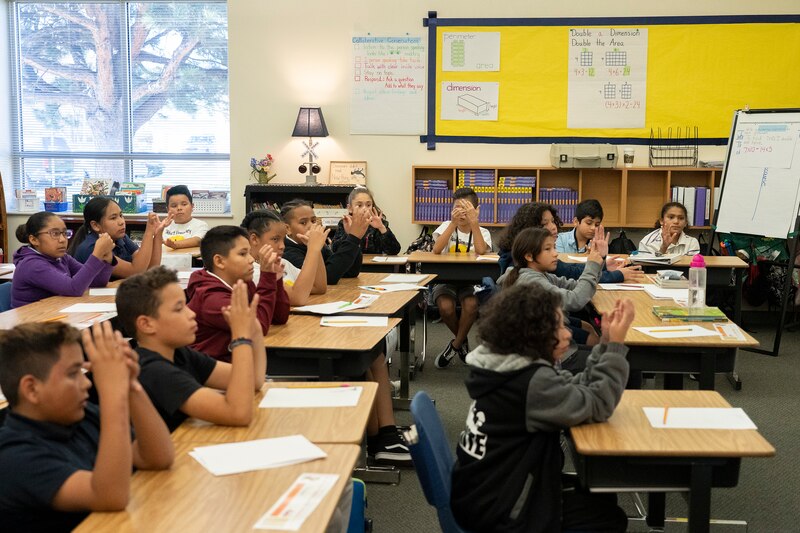

Aurora’s diversity is a strength and a challenge

The superintendent search firm’s community surveys and forums found that people view the diversity of the Aurora school community as special and a challenge. The district struggles at times to meet the needs of all of its students and to retain a workforce that is reflective of its student body.

According to the district’s website, the district’s 38,000-plus students come from over 130 countries and speak more than 160 languages. About 56% of students are Hispanic, 18% are Black, 13.4% are white, and 5% are Asian. Nearly 75% of the district’s students qualify for subsidized meals, an indicator of poverty.

“We need a good leader in our school because schools often serve as anchors for the community and often serve as safe spaces for immigrants and refugee youth,” said Harry Budisidharta, executive director of Aurora’s Asian Pacific Development Center.

“We need a leader that has experience working with diverse communities and has a track record of building bridges.”

Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman said he hopes the district continues its after-school programs, supported by a 2018 voter-approved tax increase. They are a great place for kids when parents are working late, he said, and the city needs to offer students safe spaces. These programs also offer physical activities and help students with academics and social and emotional needs.

“Here you have essentially working families that are relatively poor and to relieve them of essentially a lot of day care costs and in a great environment for the kids, we couldn’t replicate that as a city, yet it’s something we’re trying to do,” Coffman said.

Community members overwhelmingly said APS needs someone who has a record of addressing the needs of a diverse student body, including breaking barriers for non-English speaking students and their families.

“We’re quick to talk about diversity, how diversity-rich Aurora is, but that also comes with responsibility,” said Brownlee of the Community College of Aurora. “We can’t just dwell here; we’ve got to take care of and create these pathways for economic mobility for these families. The American dream has to be realized, and education is critical in that.”

Student needs include mental health alongside academics

Several people said the next superintendent must ensure the district cares for its diverse community — including its mental health.

Students in Aurora are dealing with a lot. Teachers report that many are disengaged after frequent pandemic-related school disruptions. Some are juggling jobs and caring for siblings or have lost housing due to rising rents.

In 2021 two shootings outside high schools injured nine students and renewed conversations about gun violence and youth gang activity. More recent shootings haven’t occurred on school property, but community violence continues to affect students.

In focus groups with high school students, the search firm found that two main issues were violence and drugs in schools. Some students don’t feel safe walking to school and have called for better transportation options.

Aurora’s school district added mental health supports for students and staff and budgeted millions of dollars in federal pandemic relief funding for social and emotional learning programs designed to boost students’ well-being.

Reed-Ellis said that she believes continuing to provide these types of support — for employees as well as students — is paramount.

“How do we create schools that are truly responsive to our new world?” she said. “A lot of that seems to be around mental health and social emotional learning for students and adults.”

Budisidharta agrees that youth mental health is one of the area’s most pressing issues.

“We need a leader that will champion and prioritize mental health services and work with local community partners to make sure these youth get the mental health services they need regardless of their ethnicity or immigration status or income,” he said.

None of this will be easy, but the right superintendent candidate will see more than challenges, community leaders said.

“You don’t see problems, you see opportunities,” Brownlee said. “For someone that’s looking at this opportunity, it needs to be purpose work. It needs to be why you’ve been put here to do this work.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.

Carina Julig is a reporter for Sentinel Colorado covering education in Aurora. Contact Carina at cjulig@sentinelcolorado.com.