Some Democratic lawmakers want more protections for Colorado students facing expulsion — including training for administrators and a guarantee that families will get at least two days to review the case against their child.

The bill is a scaled-back version of legislation that was killed earlier this month after widespread opposition from school district administrators who feared that limiting expulsions would make schools less safe. That bill would have made it harder to expel students for things they did outside of school and would have given students more due process rights.

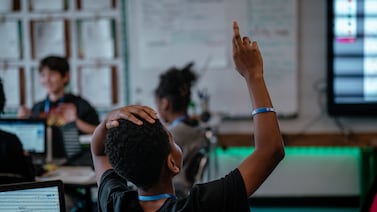

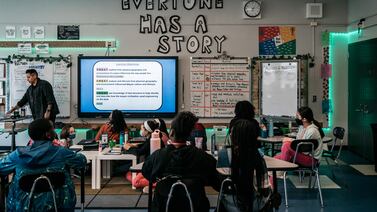

The effort to limit expulsions comes amid debate about school safety and discipline. Educators have reported more student behavior problems in the wake of pandemic closures, while rising community violence has shown up repeatedly at the schoolhouse door. Advocates for youth, though, worry that removing students from school cuts them off from positive influences, derails their education, and makes it more likely they’ll end up in the criminal justice system.

Democratic state Rep. Serena Gonzales-Gutierrez of Denver and state Rep. Junie Joseph of Boulder are sponsoring the legislation. Gonzales-Gutierrez has spent her career in the child welfare and juvenile justice system in various capacities.

“I’ve seen firsthand what happens to kids who are not afforded due process in the school system and then put on a trajectory toward more system involvement,” she said.

House Bill 1291 would clarify that school districts have the burden of proving by a preponderance of evidence that a student violated state law and school district policy, that alternative remedies aren’t appropriate, and that keeping the student out of school is the only way to preserve the school’s learning environment.

Schools would have to show that it’s more likely than not that the student committed the offenses of which they are accused. It’s the same burden of proof that’s used in most civil lawsuits.

The bill also would require that school districts provide all the evidence they plan to use in an expulsion hearing to a student’s parent or guardian at least two business days before the hearing.

And it would require that hearing officers complete a training that covers topics such as child and adolescent brain development, trauma-informed practices, restorative justice, bias in disciplinary practices, and applicable state and federal law.

Over hours of testimony in support of the earlier bill, current and former students described being kicked out for behavior that stemmed from abuse and neglect. Others described being expelled for fights that happened over the summer or for being a member of a group chat in which someone else made a threat.

Barbara Garza, now a social worker at AUL charter school in Denver, described being expelled as a student. She later went on to earn her master’s degree at the University of Denver so she could help kids like herself.

“Adults always made me feel like school was not for me,” she said. “I always heard, ‘She just doesn’t try hard enough.’ During that time, I was trying hard.

“I had a lot of responsibilities. I was experiencing abuse. But adults had already made up their mind about who I was going to be and what box I fit into. I felt like people were using my behavior as a child to define what kind of adult I would be.”

State data from the 2021-22 school year shows that about a third of expulsions were for assault, weapons offenses, or felonies. The other two-thirds were for violations related to drugs and alcohol, defiance and disobedience, or destruction of school property. The single largest category — 214 out of 794 expulsions — was “detrimental behavior.”

Gonzales-Gutierrez had originally hoped to make it much harder to expel students for nonviolent offenses or for behavior that occurred off school property, such as a fight at the mall, unless administrators could show a “substantial nexus” with the school setting. She also wanted to allow students to cross-examine witnesses and have other rights they would have in a court setting.

That bill already faced a difficult path forward, with strong opposition led by the Colorado Association of School Executives, which represents superintendents, principals, and other administrators. They said expulsion is already a last resort, and they carry a heavy responsibility to keep an entire community safe. State law leaves school districts legally liable if they overlook known threats, and someone is harmed.

Then on March 22, a student who was on probation for a weapons charge and who had previously been removed from the Cherry Creek School District shot and wounded two administrators at Denver’s East High School. The student later died by suicide.

Two weeks later, Gonzales-Gutierrez withdrew her original bill, asking that the House Education Committee postpone it indefinitely, but pledged to bring back some protections for students facing disciplinary action.

She said her bill would not have changed anything about what happened at East High School. The bill still would have allowed expulsions for violent offenses and weapons-related offenses. And Denver Public Schools never sought to remove the student, who was on a safety plan that required daily searches.

She said the focus needs to be on providing more mental health services and other support.

“We are failing our students,” she said. “We failed that young man who took his own life and caused harm to others.”

She hopes this bill is a “fresh start” to the conversation.

CASE Executive Director Bret Miles said he appreciates the change in approach, though his group still has concerns about the most recent legislation. He’s not opposed to training or guaranteeing families time to review evidence, he said, but in general he thinks the current system is working.

Anything that would make it harder to expel students puts administrators in a difficult position, he said.

“What has become incredibly clear over the last few weeks is the impossible job principals have to work with all their families to balance the educational needs of all students,” he said. “Principals care about the most disenfranchised kid in their school. They want that kid to get what they need. And then they have other parents saying, ‘Why is my student put at risk or suffering or in harm’s way or afraid?’”

While administrators aren’t on board yet, the approach of Colorado’s Democratic legislature stands in contrast to other states where lawmakers are making it easier to kick disruptive students out of school. No such bills have been introduced in Colorado.

The expulsions bill is scheduled for a hearing before the House Education Committee April 20.

Bureau Chief Erica Meltzer covers education policy and politics and oversees Chalkbeat Colorado’s education coverage. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.