A Denver school board discussion of police in schools Monday began with board members shouting to be heard after the president cut off their microphones and ended with a series of ministers praying that the district’s children be safe and that its leaders show good judgment.

“This topic is too important for us to gloss over,” board member Michelle Quattlebaum, who opposes stationing police officers inside schools, said after her microphone was cut off. “I will continue to press back on structures of oppression.”

The tumult at Monday night’s Denver school board meeting reflected ongoing conflict on the board, the deep division in the community over police in schools, and how strongly each side feels their solution is safest for students. The debate follows several incidents of gun violence, including a shooting inside East High in March that prompted the board to temporarily lift a ban on police in schools.

Now the board is weighing whether to bring the officers back on a long-term basis. But with dueling proposals on the table, the seven board members don’t agree.

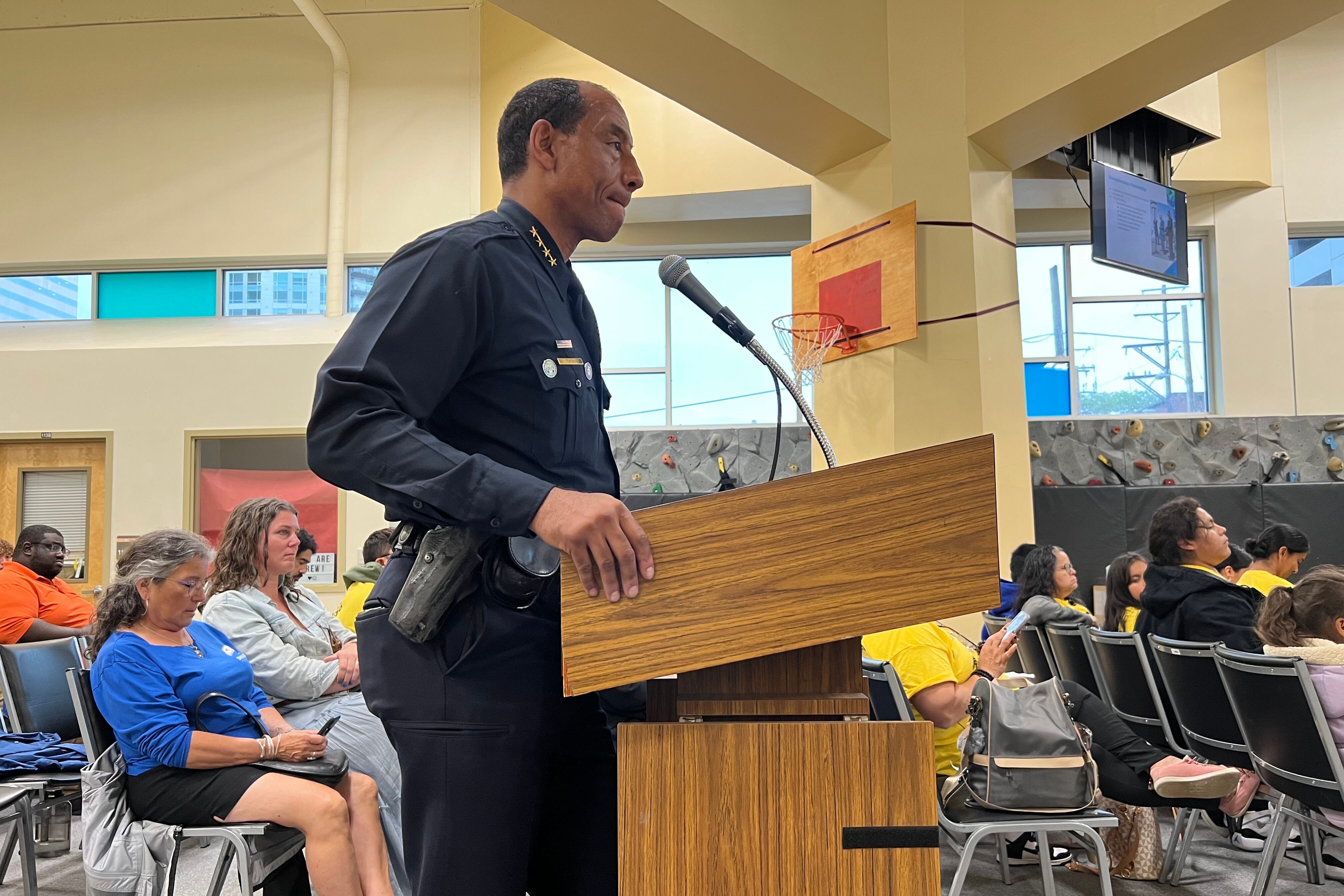

Superintendent Alex Marrero invited Denver Police Chief Ron Thomas to Monday’s meeting to explain how police would partner with Denver Public Schools if the board reinstates school resource officers, known as SROs. The agenda item read only “Superintendent’s Update.”

Thomas promised specialized training in de-escalation and the adolescent brain. He pledged that the officers would come from the community and want the assignment. He said they would focus on positive interactions with students and deterring crime, not on discipline.

“I’ve seen it work where young people have had a great opportunity to develop relationships with police officers in their schools,” Thomas said.

Deputy Superintendent Tony Smith then read off a long list of just-in survey results overwhelmingly in favor of police: 95% of students at Montbello High, 90% of parents at Northeast Early College, and 85% of staff at Lincoln High are in support of SROs, Smith said.

The results were notably different from previous survey results. An April survey conducted by the district found just 41% of students in favor of SROs. At a series of telephone town hall meetings last month, parents consistently ranked SROs second behind weapons detections systems as the resource they wanted DPS to invest more money in.

Quattlebaum questioned the validity of the survey results presented by Smith. Black students, she said, “do not feel safe speaking their truth” for fear of being seen as opposing school safety. The survey, she said, supports what Marrero, board President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán, and board members Scott Baldermann and Charmaine Lindsay want: to return SROs to schools.

“But have we done the real research, is what I’m asking,” Quattlebaum said. “Creating and holding the space that’s actually required to address the situation?”

Gaytán tried to cut Quattlebaum off. She said it wasn’t Quattlebaum’s turn to speak.

“Please, I ask for your respect,” Gaytán said. “As president of the board, I’m asking you kindly and respectfully to respect procedure.”

Quattlebaum kept speaking. “When we go down the list of traits of white supremacy, this is actually one of them,” she said.

Gaytán gestured toward the technical crew controlling the microphones. Board Vice President Auon’tai Anderson jumped to Quattlebaum’s defense. “Do not cut her mic!” he said.

But Gaytán did. Quattlebaum stood up and spoke loudly.

“I will continue to be a voice and a beacon,” Quattlebaum said.

Anderson’s microphone was cut off a few minutes later, after Marrero said it was “impossible to fathom” that Denver’s students of color would be over-policed by SROs under his watch, even though it happened in the past. “Then is not now,” Marrero said.

“Respectfully, Dr. Marrero, I have to just,” Anderson began.

“Vice President Anderson,” Gaytán said. “Would you please follow procedure and ask for the floor?”

“I’m not doing this with you today,” Anderson said to Gaytán.

When Anderson’s microphone went dead, he also stood up and shouted.

“Just because we have new faces doesn’t mean we trust what you’re going to do!” he said.

The board is considering two proposals. One, authored by Baldermann, would let the superintendent decide when, where, and for long SROs should be stationed in schools. While Gaytán and Lindsay have not formally endorsed Baldermann’s proposal, Gaytán called the return of SROs “inevitable,” while Lindsay has said they could help.

Another proposal, backed by Quattlebaum, Anderson and board member Scott Esserman, says the district should instead work with the city to create community resource officers who would be available to schools only when necessary.

The bulk of Monday’s meeting was set aside for public comment — and the topic of SROs dominated among the speakers in the packed auditorium. Nearly all speakers, including a large group with the advocacy organization Movimiento Poder, were opposed to bringing back SROs.

They said SROs cause trauma, ticket and arrest Black and Latino students, and do nothing to stop school shootings. They accused the school board of being reactionary and ignoring data.

“For my sake, and thousands of students’ sake, please stop ignoring the Black and brown voices,” said Carold Carter, a sophomore at Denver School of the Arts.

“It’s important we show our community of beautiful students that we truly care about them and will refuse to treat them as criminals or their schools as prisons,” the 15-year-old said.

At a press conference just a half hour before the meeting Monday, some parents expressed a more complicated view. Dorian Warren, a Black mother with a son at East High, said that the SROs at East have tried to build a rapport with her son.

Warren is part of a group called Resign DPS Board that is calling on all seven board members to step down — or at least for voters to get rid of any incumbents who run for reelection.

In a year filled with gun violence, Warren said there were no incidents after the SROs returned.

“I don’t want to see another child die and more finger pointing,” Warren said. “This board needs to be proactive and stop dragging their feet, stop making excuses, stop being divisive.”

Before Monday’s board meeting was over, Quattlebaum had apologized for “stepping out of order.” More than three hours of public comment ended with a series of nine ministers who used their allotted three minutes each to stand at the microphone and pray.

“I’ve been here for a few hours, so I’m tired,” said Brandon Washington, pastor of Embassy Christian Bible Church. “And I know you are too. One of the things that was fatiguing was not just the passage of time, but the manner in which this conversation occurred. So I want to be careful to give some attention to remembering that the agenda here is not self. It is others.”

School safety, Washington said, is “a complex matter.” “Let everyone here think the best of the other,” he said, “knowing that everyone here desires the welfare of children.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.