Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to keep up with education news in Denver and around the state.

To recruit students to Hallett Academy, Principal Dominique Jefferson said she tells the truth.

“Here at Hallett, we will love your child into learning,” Jefferson said, sitting in her quiet office on a recent Friday morning. “That is the commitment I make to you. And I keep my word.”

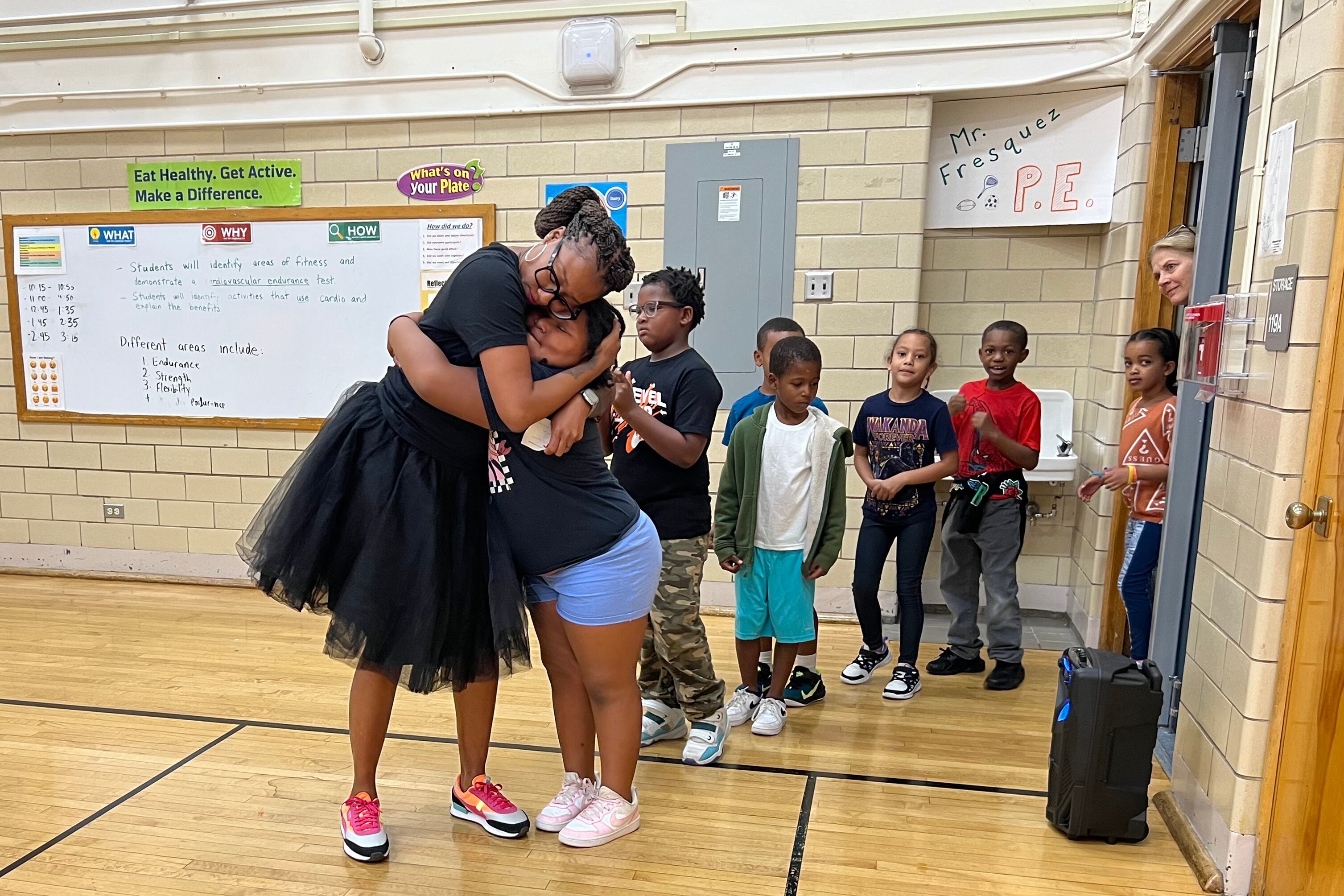

Jefferson’s commitment was clear as she moved through the hallways in a tutu, greeting students by name and opening her arms wide. At a weekly assembly in the gym, she offered a squeezy hug to each of the 289 children who wanted one before she led the entire school in a lesson about self-care, one of Hallett’s school-wide expectations.

The Friday before, she’d handed out green cupcakes — a celebration of the fact that for the first time in nearly a decade, Hallett earned the state’s highest school rating, signified by the color green, based on student progress on state tests taken this past spring.

“Life is hard for the children who look like me,” Jefferson said. “I am just committed to making sure that when they come to school every day that they experience freedom. And they are reminded of the power that they have.”

Jefferson is Black, as are 71% of Hallett students in kindergarten through fifth grade. That high proportion makes Hallett unique in Denver Public Schools, where just 14% of students are Black.

Every single student must choose to attend Hallett. That’s because the school is one of just a few Denver district-run schools without an enrollment boundary that directs neighborhood children there, a circumstance that several families said is both a blessing and a curse.

It’s a blessing because that intentionality is part of Hallett’s magic, they said. But it’s a curse because as lower birth rates and high housing costs drive down enrollment in DPS districtwide, small elementary schools like Hallett are at risk for closure.

Hallett has been closed before. In 2008, Hallett was one of eight DPS schools closed for low enrollment. The building, which is located in the historically Black neighborhood of Park Hill, reopened as the new home for a public magnet school, Knight Fundamental Academy.

Omar D. Blair, the first Black DPS school board president, helped start Knight in the early 1980s. It focused on “structured, stay-in-your-seat learning,” and posted high test scores, according to newspaper reports from the time. At Hallett, the school was renamed Hallett Fundamental Academy. As a magnet school, Hallett no longer had a boundary.

Bringing healing and restoration

When Jefferson became principal of Hallett seven years ago, one of the first things she did was rebrand the school and remove “fundamental” from its name. A few years before, Hallett had been publicly accused of cheating on standardized tests. The former principal was put on leave while the state investigated Hallett’s high scores, which had earned the school a green rating.

The investigation turned up no wrongdoing; Hallett students and staff hadn’t cheated. But it wounded the community, Jefferson said. When she arrived, the school was rated red.

“I made it my responsibility to bring healing and restoration,” Jefferson said. “I remember them being slandered and never receiving a ‘sorry.’”

To accomplish her goal, Jefferson didn’t focus on curriculum or schedule changes, or stricter rules for teachers or students, as many schools do in their attempts to boost academic performance. Her strategy was much simpler.

“In short,” she said, “I hired well.”

When interviewing job candidates, Jefferson said she doesn’t require a certain background or set of skills. She listens. She waits to hear candidates say they believe all children can learn and achieve. That when children are at school, 100% of the responsibility for their success rests with their teachers, regardless of what’s going on at home. And that the candidates feel called to work at Hallett, just as Jefferson did, even if they can’t pinpoint why.

“I wait to hear potential team members say things like, ‘This may sound strange, but I just think I’m supposed to be here,’” Jefferson said.

That’s how kindergarten teacher Joy Wills felt when she visited Hallett at the end of last school year. Wills was a teacher in a neighboring district who knew Jefferson from years ago but had no intention of leaving her job. The visit — to a school with predominantly Black students in a historically Black neighborhood — changed her mind, Wills said.

“It was great to have that sense of home community that I haven’t had since I’ve been here in Denver,” said Wills, who is from Chicago.

Hallett’s staff is diverse, and Jefferson said that she’s proud that the adult population at Hallett mirrors the student population. “If you are a white boy student, there are teachers who are white and male that you will see at least once a week,” Jefferson said. “If you are a multiracial girl, you will see, ‘Here are three multiracial folks. They look just like you.’”

At the assembly Friday, the entire school played a game called “Just Like Me.”

“If you have your hair in braids, you would stand up,” Jefferson explained to the students and staff. “And you would say, ‘Just like me!’ On the count of three: One, two, three.”

“Just like me!” the students and staff said over and over again in response to questions about whether they were left-handed, an only child, or if summer was their favorite season.

‘Children are loved here’

The cultural mirror is one of many aspects of Hallett that parents said they appreciate.

“They just do a lot to make every kid feel seen throughout the day,” said parent Amy Martinez, who described her family as multiracial: She is white, her husband is Mexican, and their first grade daughter Jaliyah is Black. “They instill that pride in the students.”

Parent Emily Nelson said that when she and her husband were looking for a school for their children, who are biracial, she was struck by how the staff at Hallett interacted with the students.

“That was probably the biggest thing, just to walk through the hallways and hear peace,” Nelson said. “Before looking at test scores or any of that, I looked at how the children were acting. The self-esteem was something I was looking for, of just fostering strong humans.”

Parents credit Jefferson with creating that atmosphere. Faith and advocacy are a big part of how she’s gotten there. When DPS tried to change Hallett’s start time this fall from 9 a.m. to 7:30 a.m. as part of a districtwide policy to have elementary schools start earlier and middle and high schools start later, Jefferson and the parents successfully pushed back.

Families come to Hallett from all over the metro area, driving up to 45 minutes from Lafayette to the north and Castle Rock to the south, Jefferson said. Starting school an hour and a half earlier would have made that journey untenable for many families.

When DPS predicted Hallett’s enrollment would dip to just 171 students in kindergarten through fifth grade this year, necessitating that Jefferson cut $697,000 — the equivalent of six and a half teachers — from the school’s budget, she decided to do something district staff told her was impossible: request DPS supplement her budget by the full $697,000.

But Superintendent Alex Marrero said yes, and then Hallett proved the predictions wrong: When school started, 225 students in kindergarten through fifth grade showed up. The school also has 64 preschool students, though preschool is funded separately.

As Jefferson sees it, the last barrier is Hallett’s lack of a boundary. Having a boundary could boost the school’s enrollment and ensure Hallett stays off any future school closure lists.

She’s holding out hope that DPS will restore the boundary, just as she had faith that Hallett would restore its green rating. After years of red ratings, the state’s lowest, and no rating last year because not enough Hallett students took the state standardized tests, Jefferson began telling everyone that Hallett would rocket to the top of the ratings chart this year.

Before third, fourth, and fifth graders took the state tests known as CMAS this past spring, Jefferson wrote each of them a personalized postcard.

“You are an extraordinary human, blooming in boldness, speaking your truth,” she wrote to Nelson’s daughter Gianna, who was in fourth grade last year. “CMAS starts soon. Show up and do your very best because you can and you are more than capable.”

The postcard is still hanging on the Nelsons’ fridge. While Nelson said test scores were never most important to her, the green rating is a public testament to the environment at Hallett.

Jefferson feels similarly.

“What I want folks to know is that children are loved here, that they are seen, that they are thriving, and we are a mystical, magical community in that whether or not we’ve been given what we need, we always have what we need,” she said.

“That’s what I want folks to know. And now they’re starting to know.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.