A Denver foundation wants to help create tens of thousands of new seats in the state’s charter schools and other settings outside district-run public schools at a time when Colorado’s school-age population is shrinking.

The effort, launched by the conservative-leaning Daniels Fund last year, is part of a larger initiative foundation leaders are calling the Education Big Bet. The goal is to put 100,000 more students in what the Daniels Fund calls “choice seats” by 2030 in a four-state region that includes Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Tapping into both the pandemic-era appetite for alternative forms of schooling and worries about COVID’s impact on learning, Daniels Fund leaders say the Big Bet is about meeting the needs of students and families.

On its face, the creation of so many new seats in charter schools, private schools, and homeschool programs could leave Colorado’s traditional public schools hurting. Many Colorado districts, including Denver, Jeffco, Aurora, and Mesa County Valley, are already facing the prospect of closing schools as enrollment declines. A flurry of new schools or seats could intensify the competition for students and put more financial stress on school districts, leading them to shut down some of their own schools.

But while the foundation’s goal is ambitious, its investment in the Big Bet is modest. In 2022, when the effort launched, the foundation spent $10 million on the initiative in the four-state region — about 20% more than it had spent on K-12 grants the year before.

The Daniels Fund, which was established with the fortune of the late billionaire cable executive Bill Daniels, is best known for its generous college scholarships. Foundation leaders say if the Big Bet is successful, the number of students learning outside district-run public schools will grow from 350,000 to 450,000 across the four states by the end of the decade — a nearly 30% increase.

Hanna Skandera, the foundation’s president and CEO, said education isn’t one-size-fits-all and that families want options so kids can pursue their passions.

“There’s nothing more powerful than giving parents and kids the opportunity to have a great education,” she said.

It’s not yet clear what the Big Bet means for students and schools in Colorado or the other three states. Experts say philanthropic efforts like the Big Bet that promote charter school growth or private school options under the banner of market competition aren’t new, though they also note that most parents give their own child’s school good marks.

A variety of groups have received grants through the Big Bet so far, including a new agriculture-focused charter school north of Denver, a group that gives private school scholarships to lower-income students, and a nonprofit that makes grants to home-school co-ops and tiny private schools, often referred to as microschools.

The Daniels Fund doesn’t plan to pay for all the new seats its leaders hope to create.

“We aren’t trying to do this alone,” said Luke Ragland, the fund’s senior vice president of grants. “We’re definitely looking to rally partners.”

Currently, the foundation has no formal Big Bet partners, but Ragland said potential partners could include other foundations, education entrepreneurs, and even families.

Jeffrey Henig, a professor of political science and education at Columbia University, said although the Daniels Fund is using private money for the Big Bet, it’s helping create infrastructure that could shift public money and support away from the traditional public school system.

“Giving some kids a better shot of getting out of their public schools may come with a big price tag in terms of democracy and public accountability,” he said.

Skandera said critics are taking an unfortunate “zero-sum view of school choice.”

“Choice programs that help students find a school that meets their unique needs usually helps both that individual student and their public school peers, something backed by significant amounts of research,” Skandera said, citing a report from EdChoice.

Daniels Fund will focus on charter seats

Three-quarters of the 100,000 new choice seats Daniels Fund leaders hope to add over the next six years are slated to be in charter schools. About 40,000 of those will be in Colorado, representing nearly 30% more charter enrollment than there is today.

Research shows that expanding charter schools puts financial stress on school districts and may require them to shut down some of their own schools.

About 15% of Colorado students already attend charter schools — one of the highest rates in the country — and the sector has grown steadily for years. But charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently run, sometimes face the same struggles traditional public schools do, including declining enrollment and spotty academic performance.

Still, charter openings often outpace charter closings. Following the closure of two Colorado charter schools at the end of the 2021-22 school year, seven new ones opened in the fall of 2022, according to the Colorado Department of Education.

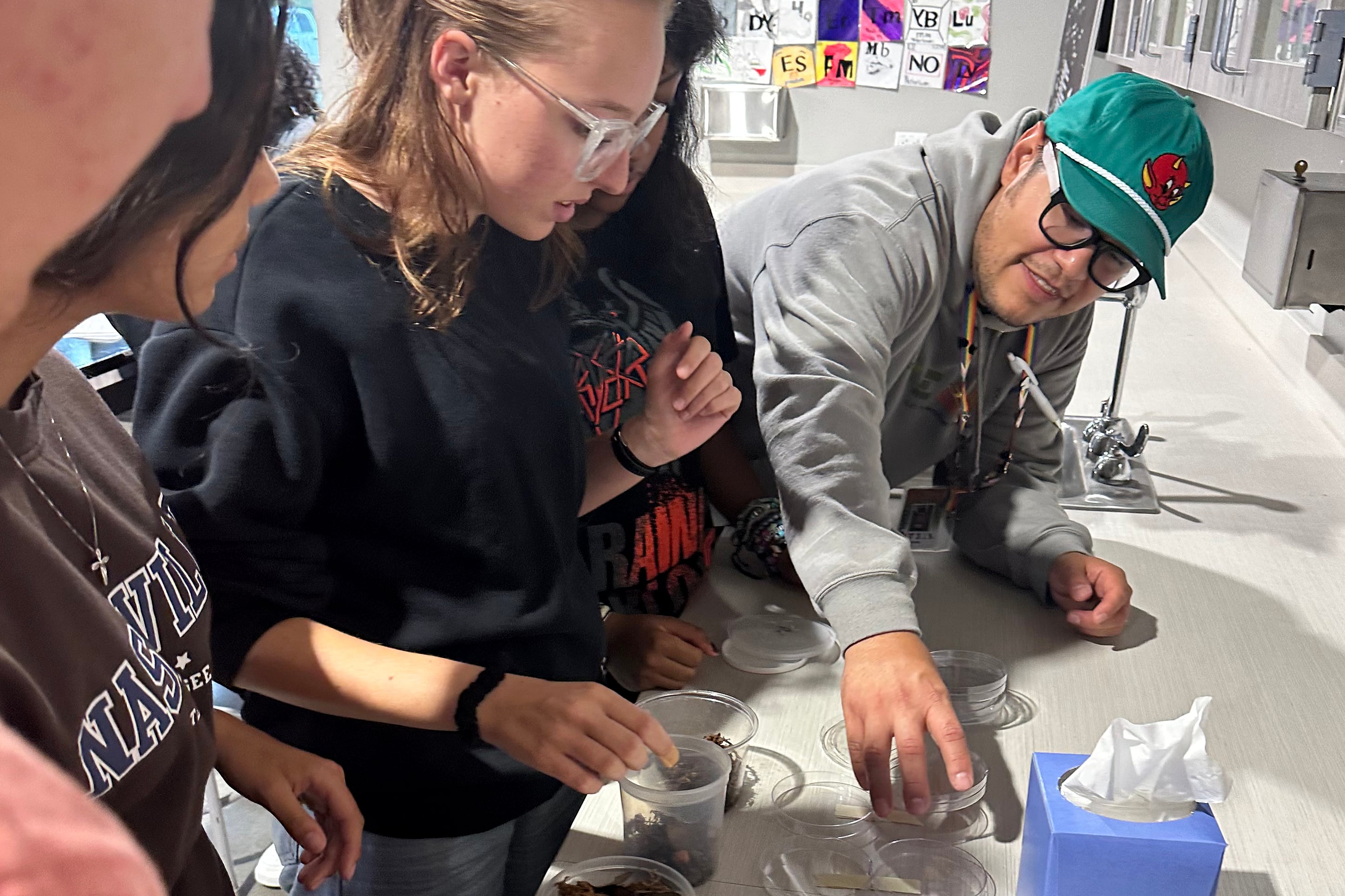

The STEAD School, a charter high school in Commerce City north of Denver, is one recent addition to Colorado’s charter school landscape. It opened in 2021 and recently landed a $280,000 Big Bet grant from the Daniels Fund that will help with staff training and curriculum planning over two years. The school — which has a soil and seed lab and takes its students to the National Western Stock Show every January — focuses on agriculture and science.

Amy Schwartz, the school’s co-founder and board chair, said STEAD leaders always planned to scale up to about 700 students, up from 273 this year in grades 9 through 11. So the Big Bet grant isn’t driving STEAD’s expansion, but without it, “the quality of our curriculum and instruction wouldn’t be where it is,” she said.

Schwartz said STEAD launched during a period of rapid growth in the Brighton-based 27J district, which authorized the charter school.

In addition to providing a unique academic focus, the school came at a time when the district “just couldn’t build school buildings fast enough,” she said.

The STEAD School has the state’s highest green rating this year.

A recent study found that students in Colorado charter schools made slightly more progress on math and reading tests than similar students in nearby district schools. This aligned with national findings.

However, there’s significant variation in performance within the charter sector.

“It’s a mixed picture, and a lot of charter schools don’t do a better job or even as good of a job as traditional public schools,” Henig said.

Big Bet also pushes for more private seats

Daniels Fund leaders hope to send about 23,000 more students to private schools or some version of home schooling in the four-state region over the next six years. In Colorado, the number is 15,000.

In service to that goal, the foundation is giving money to groups like ACE Scholarship Fund, a Colorado group that gives private school scholarships to lower income families in 12 states. More than 4,000 students in Colorado receive the partial scholarships, with families paying just $2,000 a year in tuition on average, said Norton Rainey, CEO of ACE Scholarships.

The scholarships are for religious or secular private schools that charge $8,000 to $15,000 a year, not schools that charge $20,000 or more.

Rainey said the scholarships give families more choices and help private schools fill empty seats.

“There are quite a few available seats in private schools,” he said

VELA Education Fund, an Arlington, Virginia-based funder of “small learning environments,’’ also received a Big Bet grant. The nonprofit is using the $750,000 it received last year to give dozens of smaller grants to microschools and homeschool groups, as well as to groups that create curriculum materials or otherwise support private and homeschool programs.

CEO Meredith Olson said demand has grown every year since VELA launched in 2019, both from individuals who run alternative education programs and “families who are looking for something different for their kids.” Just under half of the programs funded by the nonprofit were founded by people of color and more than 90% serve low- and middle income families, she said.

In Colorado, VELA has awarded grants to a variety of organizations. Among them are a Denver microschool called La Luz that serves sixth- and seventh-graders and emphasizes field trips and experiential learning, and Catch a Star Academy, an Aurora microschool that serves third through fifth graders who struggle academically. Both schools are tuition-free, though Catch a Star notes on its website that the tuition assistance is for the 2023-24 school year. It’s unclear if families will have to pay next year.

Microschools, like other private schools, are not regulated by the state education department or obligated to administer state tests. Skandera, of the Daniels Fund, said foundation staff ask Big Bet grantees to share student achievement outcomes, but acknowledged that they may use different tests or measures. There’s no stipulation that grantees share student achievement with the public, she said.

Recent studies in other states have found students experience either declines or no improvements in math scores while attending private schools with a voucher. However, some older studies have found more positive effects on longer-run outcomes.

Kevin Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in some cases harmful academic effects were on the order of those caused by the pandemic or Hurricane Katrina.

He also noted that families may choose a private school they like, but the school decides who to admit. That means that students with certain kinds of disabilities, those who have behavior challenges, or those who are part of the LGBTQ+ community may not be welcome.

It’s important to recognize that the last choice belongs to the school, not the family, he said.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.