Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to keep up with education news in Denver and around the state.

Monthly public comment before the Denver school board will be limited to a total of two hours going forward, a restriction that board President Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán described Thursday as a “temporary solution” to the problem of too-long meetings.

“There’s been times where we’ve stayed until midnight or 1 in the morning to hear every single constituent and parent that was coming in to share any comments or concerns,” Gaytán said during a board work session Thursday night.

“To respect each other’s time as board members, to respect the time of staff, especially, that has to stay late and put in overtime to support the board in allowing for this public comment to take place, it’s important we consider all of that in setting time limits,” she said.

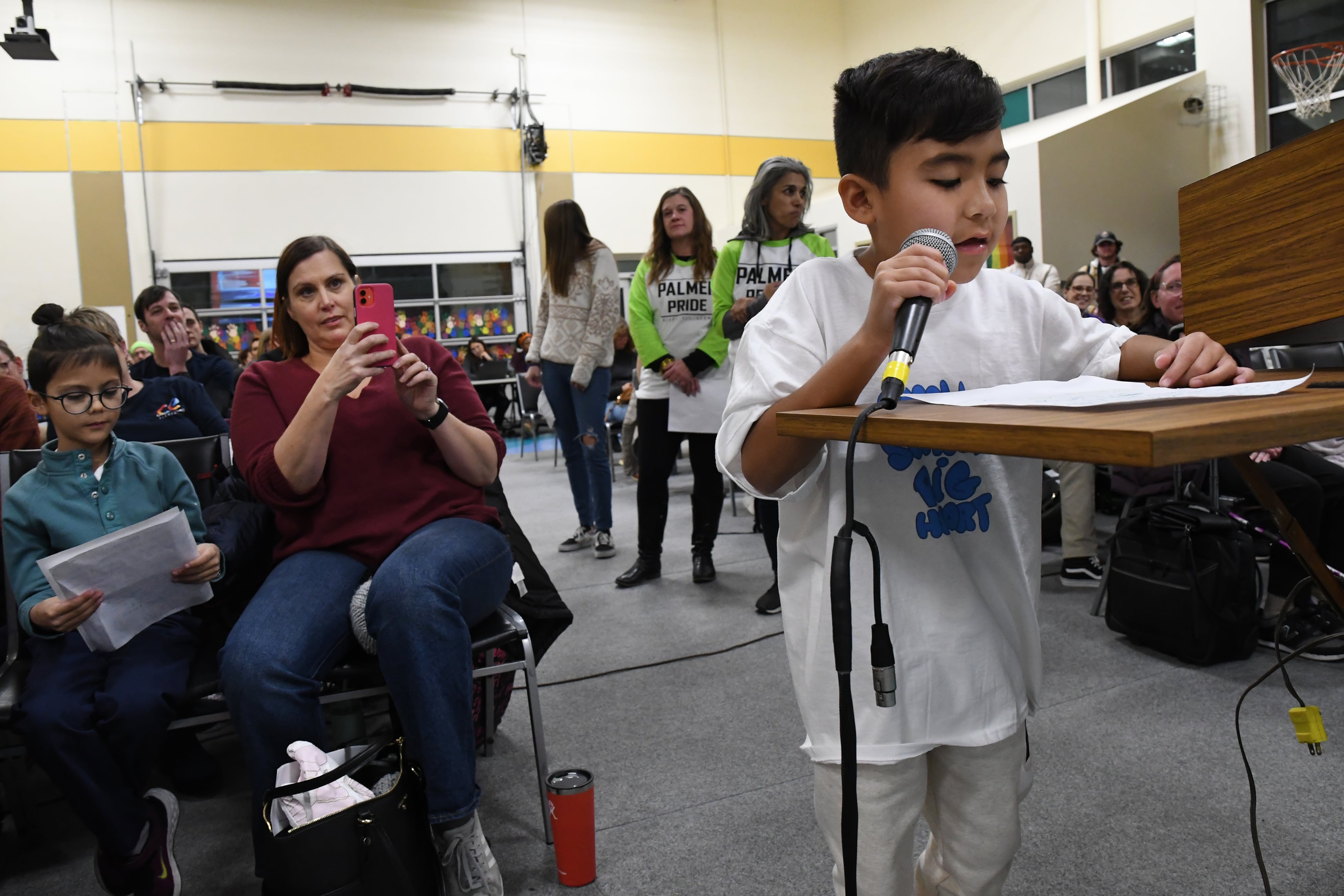

The Denver school board holds one regular public comment session per month at which students, parents, teachers, and community members can sign up in advance to address the board. The next session is scheduled for Sept. 18. The board sometimes also holds special public comment sessions on particular topics.

Speakers get three minutes each to address board members, who do not respond. If speakers go over their allotted time, the board rings a loud alarm to signal their time is up.

But until now, there was no limit on the total time for public comment, though the board has previously floated the idea. Public comment almost always stretches more than an hour, and sometimes much longer if the board is voting on a controversial issue.

A long list of speakers gave five hours of testimony in March 2022 before the board voted on a policy related to innovation schools. In November, students, parents, and teachers spent six hours pleading with the board not to close their schools because of declining enrollment.

In announcing the two-hour limit Thursday, Gaytán cited a district policy, known as policy BE, which says the board “shall set a time limit on the length of the public participation time overall, a time limit for each topic and a time limit for individual speakers.”

Two board members, Scott Esserman and Carrie Olson, volunteered to draft a new policy that would set permanent limits while the temporary two-hour limit is in place.

Member Charmaine Lindsay said she’d like to allow speakers to participate virtually like they did during the height of the pandemic. Olson floated the idea of allotting three hours instead of two because she said public comment is one of the only ways to address the board.

“We are not yet good at getting out into the community in a consistent way so that people have access to us,” said Olson, who added that she starts to fade after three hours of public comment. “It might feel like we’re cutting off more access by saying there’s only two hours.”

Melanie Asmar is a senior reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado, covering Denver Public Schools. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.