The school board of Colorado’s largest district called for all kindergarten through third grade students to be screened for dyslexia. Leaders in the Denver district said that’s happening this year. But some parents, teachers, and others are finding it hard to tell.

“I haven’t heard anything specific about a special assessment, screener, or anything regarding dyslexia,” said Lisa Williams, a second grade teacher who teaches in northwest Denver.

District leaders haven’t announced to families that dyslexia screening is taking place and aren’t tracking the number of students who show signs of having the learning disability. Instead, teachers are testing students for a variety of reading difficulties as they have in years past. It’s not what advocates who’ve long pushed for districtwide dyslexia screening envisioned and some feel like they’ve been kept in the dark about what is actually happening.

The school board mandate that Denver Superintendent Alex Marrero launch dyslexia screening is the latest development in a yearslong shift in the district’s approach to reading instruction and remediation. The changes have been driven, in part, by new state laws requiring curriculum and teacher training aligned to the science of reading, a large body of research on how children learn to read.

The mixed messages on dyslexia screening may stem from the fact that the 88,000-student district is using a version of the screening process it has used for years — one that was never focused on dyslexia specifically. In addition, many educators have long been told they don’t have the expertise or credentials to flag students for dyslexia.

While legislative efforts to mandate dyslexia screening statewide have failed repeatedly, several districts, including Boulder Valley, have rolled out their own dyslexia screening programs in recent years. Denver piloted a dyslexia screening at five elementary schools two years ago.

Jennifer Begley, the district’s director of humanities, said the current process screens for a variety of reading problems.

“The teachers you talked to would not refer to our guidance as a dyslexia screener,” she said by email. “Rather, it is our district guidance for screening, identification, and intervention in reading.”

About 15% to 20% of the population has dyslexia, a learning disability that makes it hard to identify speech sounds, decode words, and spell them. With the right instruction, students with dyslexia can do as well as their peers in school.

Denver administrators say this year’s screening process flags students who are reading below grade level, pinpoints their weak skills, and provides specially tailored reading instruction to help them improve. The process doesn’t focus on communicating explicitly to families about whether their children have signs of dyslexia.

But some parents wonder why, if the district claims to screen for dyslexia, it’s shying awaying from the term.

Denver parent Kirsten Hansen, whose two children have dyslexia, said families are notified about other kinds of screenings — for scoliosis or gifted programming, for example — and dyslexia should be no different.

“If you’re not going to tell people about it, why not?” she said. “Information is power.”

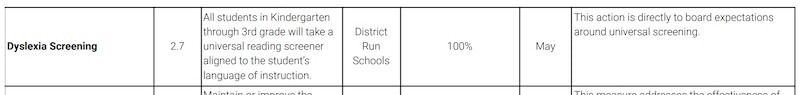

The school board will evaluate Marrero this year in part on whether all K-3 students have been screened for dyslexia. The universal screening is among dozens of performance goals that will determine how much of a bonus, potentially tens of thousands of dollars, he’ll receive next fall.

How Denver tests students for reading problems

Colorado’s landmark reading law — the READ Act — has long required schools to test kindergarten through third grade students three times a year on reading. Denver district leaders say that’s the first step of their dyslexia screening process.

Most Denver schools use an assessment available in English and Spanish called IStation, though DIBELS is another common one. Students who score below grade level on those tests are given one or more diagnostic tests to drill down on the specific areas where they struggle — perhaps phonemic awareness, phonics, or spelling.

Next, students are put into small groups to receive instruction targeting their weaknesses. If, after about six weeks of specialized help — or multiple rounds of such instruction — they don’t make progress, they may be referred to the special education team at their school for an evaluation.

The special education team may not use the word dyslexia with parents initially, but after the evaluation may share that the child has indicators of dyslexia, Begley said during a phone interview.

This year, just over half of the 25,500 K-3 students who took the initial reading assessment scored below grade level and were given diagnostic tests. Of those students, 488 students were evaluated for special education and 106 were classified as having a “specific learning disability,” an umbrella term in special education that includes dyslexia.

But despite that multi-step process, district officials said they couldn’t tell Chalkbeat how many of the 106 students have dyslexia because the eligibility criteria for that umbrella category doesn’t call out that disability. Even if all those students have dyslexia, it would represent less than half a percent of the district’s K-3 population.

Many students with dyslexia, which can range from mild to severe, don’t have a special education plan. Some have what’s called a 504 plan, which includes accommodations such as extra time to complete assignments or access to audiobooks. Some have no plan at all.

“I worry that the DPS dyslexia screener is more of a ‘low literacy screener’ and will not give many kids the one thing they need most — the actual reason for their struggles, which is dyslexia,” said Tayo McGuirk, president of DenCoKID, an advocacy group.

Struggling to read can make students feel frustrated or doubt their own intelligence. McGuirk said that when kids know dyslexia is the reason for their struggles, it can improve their mental health and their overall trajectory.

The knowledge can help parents, too. After her oldest son was found to have dyslexia, she said she became more patient and had more empathy for the way he learned.

Some Colorado districts are more transparent than Denver about flagging students for signs of dyslexia.

The Boulder Valley district has screened all kindergarteners for dyslexia since 2023, using the Mississippi Dyslexia Screener for most students. Students whose primary language is Spanish are screened using a combination of subtests pulled from different assessments. Parents receive a letter detailing the child’s overall risk level for dyslexia, as well as information about the subtests.

‘To call it dyslexia is hard’

Denver teachers and administrators say the biggest change this year in how K-3 students are screened for reading problems is that there’s more clarity about each step of the process, and about what teachers should do to help students who are behind.

“Before we’d say, ‘Oh this kid is really struggling’ and we didn’t necessarily have the right next steps to take,” said Molly Veliz, a reading intervention teacher at Marie L. Greenwood Early-8.

She said the district created a “decision tree” that tells teachers exactly how to proceed in assessing and teaching struggling readers.”It’s a super clear system,” she said.

Shelley Flanagan, a reading intervention teacher at Goldrick Elementary School, said of the district’s dyslexia screening mandate: “I’m thrilled that it’s one of the things the superintendent will be called on to follow through on.”

Flanagan, who took a college-level class on dyslexia when she became interested in the science of reading, said teachers have historically been discouraged from using the term dyslexia even when the signs point to that disability. Doctors or psychologists were seen as the ones who could legitimately identify it.

“To call it dyslexia is hard for us as teachers,” she said. “I think it’s rare to find people who will call it that.”

But Flanagan thinks many parents would feel better “knowing these are a team of experts and they’ll let me know if they see some signs of dyslexia.”

Some teachers told Chalkbeat the dyslexia label can be shocking to parents, or that it’s not as important to name dyslexia as it is to ensure children get help on the skills where they’re weak.

Robert Frantum-Allen, the district’s former director of special education and the architect of Denver’s dyslexia screening pilot, said it’s outside a general education teacher’s job scope to tell parents a child could have dyslexia.

He said students can struggle to read words for all kinds of reasons: dyslexia, ADHD, vision problems, hearing impairment, or because they were not taught properly.

“A screening tells us there is a problem, but the problem isn’t always dyslexia. It just says we need to do a diagnostic assessment,” he said.

Experts says teachers need specific dyslexia training

In the spring of 2022, Denver piloted a dyslexia screening program at five elementary schools. It used several of the same components in use now, including the initial reading test and some of the diagnostic tests.

But it also used other tools, including a teacher survey called the Shaywitz Dyslexia Screener and a parent survey asking about the child’s reading ability and any family history of reading problems. Unlike the district-wide screening program today, pilot schools also sent parents explicit information about their child’s risk for dyslexia.

The Shaywitz Dyslexia Screener and the parent survey are not part of the district’s current dyslexia screening process. Frantum-Allen said the pilot found that the Shaywitz Dyslexia Screener was reliable when filled out by highly knowledgeable teachers, but not novice teachers. Asked why family surveys aren’t part of this year’s dyslexia screening process, district officials didn’t provide an answer Friday.

Frantum-Allen said one of the biggest takeaways from the pilot was the need for teacher training specifically on dyslexia. He said the state-mandated science of reading training that all K-3 teachers have to take doesn’t dive deeply into the topic. LETRS — another well-regarded reading training that some Denver teachers are taking now — also doesn’t delve deeply into dyslexia, he said.

As special education director, he oversaw some training on dyslexia, but “not to the level I think should be there.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.