Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

This school year has been overwhelming for teachers like Joel Mollman.

As an English language development teacher at Hamilton Middle School in Denver, Mollman has had to take on more work to keep up with the growing number of students who need help learning English.

In previous years, for example, his school might have only received three students a month who needed to be screened for English fluency. This year, he screens at least three new students each week — a process that takes one to two hours per student.

“It could quickly take up two of my mornings where I could be in classrooms,” Mollman said.

Across the state, English language development teachers describe similar scenarios.

As many schools have experienced an influx of new students with limited English skills all year, their roles have been changing.

Traditionally, these teachers are tasked with screening new students, teaching English as a second language, administering English fluency tests, and coaching other classroom teachers.

Now they must also support many students who are new to the country in much larger classes than typical.

As of the end of February, seven of Colorado’s districts — Denver, Aurora, Cherry Creek, Greeley, Adams 12, Jeffco, and Mapleton — told Chalkbeat they had enrolled more than 5,600 students new to the country after October count.

Some schools, in particular ones where there haven’t traditionally been large numbers of English learners, have relied on their English language development teachers to be the main support for children new to the country. Some of the teachers describe helping students and their families navigate a new country, and even taking in a child whose family was living in a car, during a bout of chickenpox.

Often, they say, certain parts of their job have fallen to the wayside, and state advocates say that in small districts, even screening students to identify their English needs, a crucial step, gets skipped.

Cynthia Trinidad-Sheahan, president of the Colorado Association for Bilingual Education, said districts don’t have the manpower, and often don’t know what to do.

“The expertise is lacking with some of the districts,” Trinidad-Sheahan said. “How do we get training to the teachers that are in these rural districts? And it’s not just on the paraeducators and teachers. The administrators leading these buildings do not have a clear understanding of language acquisition.”

Teachers start by testing for English fluency

When a student who is suspected of not being fluent in English is enrolled in school, the district is required to screen them to identify their language level and needs for services. That screening is supposed to happen within two weeks of enrollment.

In a typical year, that occupies time in the beginning of the school year for English language development teachers. This year, with some schools receiving new students every week, that process has taken up a lot more time.

At Hamilton Middle, where Mollman is also team lead for the school’s multilingual team, he’s taken on the role of screening all students this semester. Official state numbers show 40% of Hamilton’s 700 students have been identified as English learners.

In addition to administering the tests, Mollman has to block off a few hours per week to do the paperwork for the district. That requires entering scores and other information into the computer, and three school staff members to sign off.

Last semester, another English language development teacher on his team was sharing the load, but with so many new students, that teacher had to take on another class, giving up one of her free periods. Mollman now does all the screening.

Each Monday, he starts his week preparing for testing, double-checking the schedules given to new students to make sure they’re in the right classes, tracking down Chromebooks if they haven’t received them, and sometimes making calls as he tries to figure out what proficiency the new students have in their native language.

Kayli Brooks, a teacher at Tollgate Elementary in Aurora, said screening new students didn’t consume her job only because her school was able to get help from Aurora district leaders who stepped in to do that work.

But she recalls how many of the students arrived just before the annual testing window for ACCESS tests, the tests English learners take each year to measure their progress in English fluency. Those students had to take both tests within days or weeks.

“Every office or room was filled with testing,” Brooks said. She said it was heartbreaking to pull students and have them realize they had to take yet another English test they wouldn’t be able to do well on.

It’s hard to find time to help more students

Both Brooks and Mollman said that in their schools, giving students a block of English language instruction — a legally required practice — has not stopped.

But other help for students and staff has.

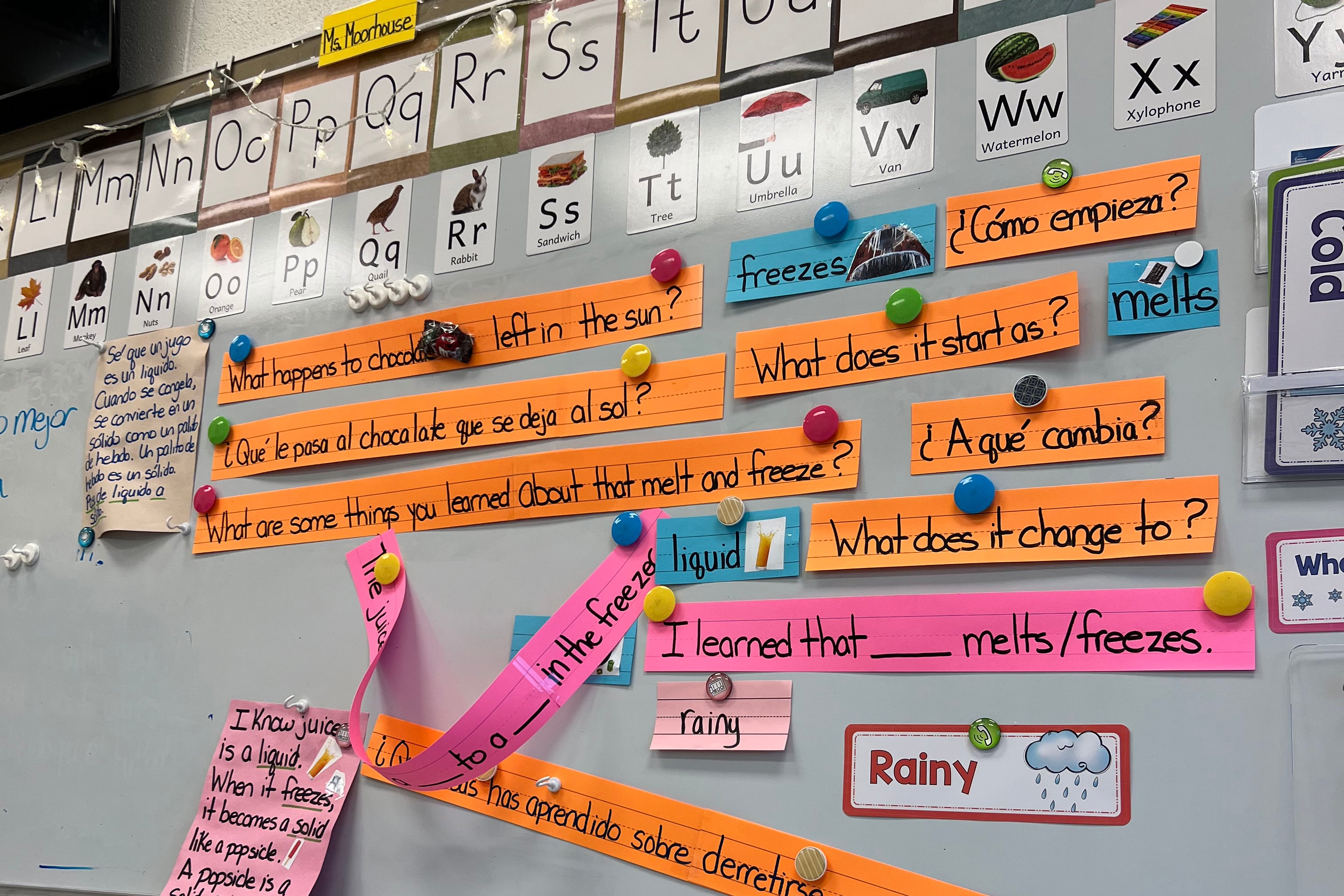

Brooks, for instance, said she used to pull groups of students such as those new to the country out of class for extra English instruction where she would let them practice speaking. She used to cater those sessions to phrases and vocabulary the students might encounter in other content classrooms such as science or social studies so they might feel more able to participate.

“All of that stopped,” Brooks said. “It came to an absolute screeching halt.”

In recent weeks, as the number of new students has slowed, she started back on a rhythm of reconvening some small groups of students.

“They are so happy,” Brooks said. “They want to learn. I taught them last week some basic advocacy: I need water. I need the bathroom. I need food.”

Still, she isn’t doing as much as she would like. And she hasn’t been able to help other classroom teachers in her school. At Tollgate, she said, about 60% to 75% of students are considered level 1 English learners, which means they don’t have any English fluency.

“We have a little over half of every classroom filled with students who don’t speak English, so half of their students are understanding what they say,” Brooks said. “Our team wants to — and should be — supporting teachers and having professional development around this. It’s just been such an overwhelming time that it’s not something that’s happening.”

Trinidad-Sheahan said districts need to allow English language development teachers to coach other teachers so the responsibilities for teaching students gets shared.

At the schools seeing an influx of emerging bilingual students, she said, instructional coaches should be teachers with experience in teaching English learners.

Mollman said at his Denver school, his team is trying to help other content teachers, but “we’re still trying to figure out the best way to do this.”

In other years, at his school teachers may have paired new students with other students who also speak the same language. But with so many new students, including some who speak Spanish and others who speak Arabic, it’s not always possible.

He’s also trying to get teachers to adapt how they grade students who don’t yet speak English. But it’s all a challenge.

“Some teachers are very good at adapting,” Mollman said. “Some have really struggled with it and we haven’t quite found the solution.”

Teachers feel unprepared for student needs

Even teachers who have experience working with students learning English as a new language say they’ve felt unprepared at times this year.

Dakota Prosch, is an English language teacher at Academia Ana Marie Sandoval in Denver, where she teaches fourth, fifth, and sixth grade students at the dual language Montessori school. In a typical year, her students are already close to fully bilingual. Because of the school model, and being a magnet school, most students by fourth grade have been in the school since kindergarten.

But this year, because of the large numbers of migrant students in Denver, the school has had to accept new students. It means Prosch is now working with students who have just arrived in the country and speak no English.

“We don’t have any materials for students who don’t speak English,” she said.

In February, the district provided some materials used at newcomer centers, but Prosch wishes she had gotten those resources sooner. For at least 30 minutes a day, she pulls aside the new students to work with them on some English development.

“There’s essentially two classes in one,” Prosch said. “I cannot deliver the same instruction.”

Most of her students are usually analyzing text. She tries to have her new students do that too, but many are just trying to learn what a sentence is and “how to put their tongue between their teeth” to learn the sounds different letter combinations make.

Still, Prosch said, “they’re really awesome kids and I’m really glad to have them.” It’s a sentiment echoed by other teachers.

Lawmakers are discussing a plan that would give some school districts additional funding for the students new to the country who have enrolled after October count when school funding is set.

Mollman agrees that more resources would help.

Right now, he said, schools like his are making tough decisions, such as choosing between bringing in a second English language development teacher or another science teacher. At his school, this year, they added a new ELD teacher to relieve a class that had more than 40 students.

“It was a pretty easy decision this year, but that then impacted one of our teams more severely than others,” Mollman said.

But, even without funding, teachers say their roles have to adapt to meet the needs of students.

“The goal is to ensure all of our students are successful regardless if they’re language learners or not,” Mollman said.

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.