Sixth grade science teacher Savannah Perkins described a surprise meeting with her school principal in early January. He told her that she would no longer be teaching science because too many students were reading below grade level, she said. Her job would “pivot” to reading intervention for second semester.

The decision meant that about half of the sixth graders at the Denver charter school — Rocky Mountain Prep-Federal — would finish the year without taking their scheduled semester-long science class. The other half had taken science with Perkins first semester.

The 380-student Federal campus is not the only one of Rocky Mountain Prep’s five middle schools where students have experienced instructional changes. Perkins said Principal Robert Barrett told her the network’s other four middle schools were also cutting either second-semester science or social studies classes for sixth graders. Barrett didn’t respond to messages from Chalkbeat.

The move, by a network that prides itself on providing its mostly low-income and Latino students with a rigorous college prep education, is misguided, some experts say, but nothing new in education. Particularly since the federal 2001 “No Child Left Behind” law put increased emphasis on testing, many schools have shaved minutes off less-tested or non-tested subjects ranging from science and social studies to art, music, and physical education.

Not only do such policies turn reading into a punishment, they cast the missing subjects as a privilege not a right, said Daniel Morales-Doyle, an associate professor of science education at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“Canceling science class for what usually amounts to more reading drills turns science into something that’s only for kids who are fortunate enough to attend schools with high test scores,” he said. “We wouldn’t see it in a wealthier, whiter setting.”

Asked for a response to Morales-Doyle’s suggestion that such measures are applied inequitably, Indrina Kanth, Rocky Mountain Prep’s chief growth officer, wrote in an email to Chalkbeat that American society historically has worked to ensure that Black and Brown children did not learn to read.

“That is an educational injustice that we are working to correct,” she wrote.

The decision to scrap sixth grade science classes is among a host of changes at Rocky Mountain Prep over the last year, and comes after a tumultuous merger last summer between Rocky Mountain Prep and another prominent Denver charter network, STRIVE Prep. That merger, spearheaded by CEO Tricia Noyola, was intended to cut administrative costs and strengthen academics, but it also led to significant staff turnover and what some employees said was a singleminded focus on test scores.

Kanth said by email that the network has a right to make “programmatic adjustments” and a “moral obligation to ensure our students are reading on grade level so they can excel in academic content and beyond.”

She declined to detail which middle schools cut science class and which cut social studies class, how the missed material would be made up, and whether next year’s sixth graders will get science and social studies classes. Noyola didn’t respond to Chalkbeat’s request for answers to outstanding questions.

Rocky Mountain Prep’s Board Chair Patrick Donovan sent a statement signed by all eight board members Friday saying the board supports the charter network’s leadership and is confident that its schools are “providing an educational experience that goes far beyond the requirements.”

Charter school leaders see a reading crisis

Leaders at Rocky Mountain Prep raised alarm about low reading scores at the networks’ five middle schools and two high schools last fall. Half of middle schoolers were reading below a third grade level and 90% of high schoolers were reading below a high school level, according to minutes from a network board meeting on November 3.

Two months later, charter network officials instituted new reading intervention classes for sixth graders. Parents at the Federal campus were notified that their children would receive additional reading help and that their schedules would change, but not that science had gone by the wayside, said Perkins, who left her job two weeks ago.

Kanth, by email, described parents as “nothing but enthusiastic about additional time for their students in reading,” but declined to respond to a question about whether parents were explicitly told their children were missing science or social studies class.

The vast majority of students at Rocky Mountain Prep - Federal are Latino and qualify for free or reduced-price school meals. Nearly two-thirds are classified as English learners.

Morales-Doyle said English proficiency is often used as a gatekeeper that prevents English learners from accessing all subjects.

“This sounds like a classic case of a deficit view causing a school to make bad decisions about what their students deserve,” he said.

Officials from the Colorado Department of Education say schools are required to teach a broad set of state science and social studies standards during middle school and those standards are usually covered over three years. But there are no specific rules about what must be covered when.

“It’s entirely up to the district to decide what that program looks like and how they structure it in their school day,” said Joanna Bruno, the department’s executive director of teaching and learning.

In Colorado, students take state math and literacy tests every year of middle school but take science tests only in eighth grade.

A spokesman for the Denver school district, which authorizes Rocky Mountain Prep’s dozen charter schools, said charter schools are required under their contracts to meet or exceed Colorado’s academic standards. He said district officials would investigate if they were notified of a potential charter school contract violation.

Students react to losing science

Perkins said she was shocked when she found out her daily 75-minute science class would be converted to a reading class. The news came early in second semester after she’d finished a few introductory lessons on science safety.

The decision meant that around 65 students would miss her planned lessons on plate tectonics, thermal energy, geology, and climate change. They were upset.

“I had multiple kids that were in tears … because I really hyped up science,” she said.

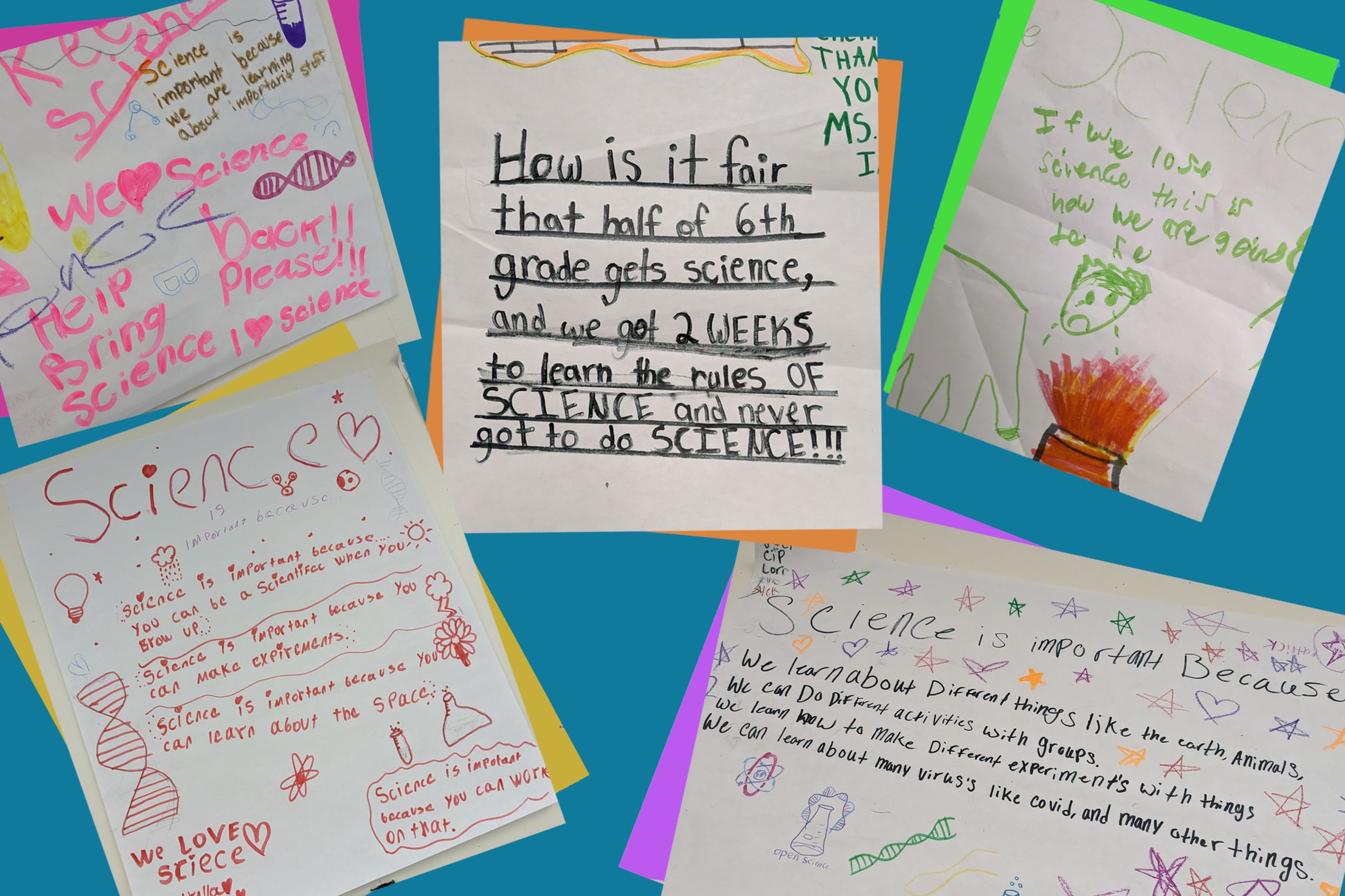

After the decision to cut science, Perkins assigned her sixth graders to make posters about the importance of the subject. Her students decorated them with twisty DNA strands, bubbling test tubes, and electrons orbiting atoms. One sixth grader wrote in black magic marker, “How is it fair that half of sixth grade gets science and we got two weeks to learn the rules of SCIENCE and never got to do SCIENCE!!!”

Perkins said she and other teachers at her school received one day of training on the elementary reading curriculum they’d be using for middle school intervention — Core Knowledge Language Arts.

Reading intervention classes started the following week, with Perkins teaching one group of sixth graders reading at a second grade level and two groups of sixth graders reading at a fourth grade level. At least 20 students who’d been scheduled to take second semester science with Perkins were put back into social studies — a class they’d taken first semester — because they didn’t need extra reading help. Perkins said their social studies teacher worked to change world history lessons so it wouldn’t all be a repeat for them.

Perkins felt frustrated that the reading lessons she led were for much younger students.

“It’s just not designed to be used for 12-year-olds,” she said, noting that some of her students were relegated to reading bedtime stories, including one about a hedgehog running a race and another about a pancake that jumped out of a frying pan.

Experts say science, social studies lessons boost reading

Rocky Mountain Prep’s middle schools are hardly the only ones with lagging reading scores, especially for sixth graders who were second graders when the pandemic closed down school buildings four years ago.

Autumn Rivera, a sixth grade science teacher in the Roaring Fork district and president-elect of the Colorado Association of Science Teachers, said she understands the sense of urgency in addressing weak reading skills because she has struggling readers in her classroom, too.

“School is easier and life is easier when you can read well and so I understand the emergency feeling around trying to help students’ reading scores,” she said.

But taking away science or social studies is not the answer, she said. One of the best ways to boost reading skills is to incorporate reading practice into content areas where students are learning about the world and topics that interest them, she said.

“Science is such a great place — and social studies — for students to get so excited about what they’re learning, they don’t even realize they’re reading,” she said.

Rivera, who won Colorado’s 2022 Teacher of the Year award, recently saw this happen for one struggling reader during a unit on how palm oil impacts orangutan habitat in Indonesia. After the class read an article about palm oil production, the normally quiet boy, “for the first time, raised his hand and shared out an answer with confidence because he knew he had found it,” she said.

Perkins had hoped to teach at Rocky Mountain Prep’s Federal campus through the end of the school year despite misgivings that began when the two charter networks merged last summer.

“I was planning on staying for my love of science and my love for this group of kids,” After the second-semester shake-up, she said, “I lost both of the reasons I was staying.”

Perkins now teaches seventh grade science in a nearby school district.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.