Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Colorado school districts with four-day weeks have slightly lower student achievement on average than those with five-day weeks and see little improvement in teacher turnover after shifting from five to four days.

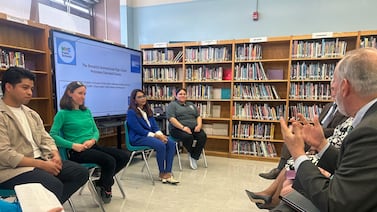

That’s according to a new report from the Keystone Policy Center that argues for stricter guardrails on four-day school weeks and the creation of an expert panel to study the issue.

The report, “Doing Less With Less,” comes at a time when nearly two-thirds of Colorado’s 185 districts — enrolling about 14% of the state’s students — operate on four-day-a-week schedules. In the last five years, about two dozen districts across the state, most small and rural, made the switch. This year, the 1,200-student Strasburg district, about 30 miles east of Denver, is the only district changing to a four-day schedule, according to the Colorado Department of Education.

“There’s this growing movement around four-day school weeks, and as far as I know, there haven’t been any public discussions around the merits of it,” said Van Schoales, senior policy director at Keystone. “I mean, every district that’s applied for waivers [from five-day-weeks] has gotten them. It’s been a rubber-stamp process.”

Keystone’s report, citing both state and national research and anecdotes from district leaders, concludes that having fewer school days per week doesn’t generally help kids academically.

“The trend toward four-day school weeks in Colorado does not provide a net benefit to the state’s public school students,” the report says. “In fact, student achievement is not even the top consideration when districts make the switch.”

Instead, the primary rationale is to help recruit and retain teachers by offering the shorter week as an employment perk.

While some district leaders told Keystone that four-day weeks have given them a competitive advantage when it comes to staffing, the report concludes that the schedules often don’t make a big difference

As an example, it describes how when the tiny Dolores district in southwestern Colorado switched to a four-day week a few years ago, teacher departures slowed at first. But when a larger nearby district adopted a four-day week the next year, the advantage melted away.

“So now we’re all just back to fighting over who can pay their people more and benefits and things like that,” Superintendent Reece Blincoe said in the report.

The report also highlights the experience of District 27J, a 23,000-student district based in the Denver suburb of Brighton, the largest to have made the switch.

District leaders took the plunge in the 2018-19 school year after voters repeatedly rejected ballot measures that would have helped boost teacher pay. They figured the attractive schedule would pull in and keep teachers otherwise turned off by the district’s low salaries.

But a study by Brown University researchers cited in the Keystone report found that experienced teachers were 5 percentage points less likely to return to 27J after the switch to a four-day week. It wasn’t because teachers didn’t appreciate the shorter school week, but rather because the schedule didn’t outweigh the draw of higher salaries elsewhere.

The Keystone report urges policymakers to consider fixes to the teacher recruitment and retention problem, including higher pay for rural teachers and housing help in districts with a shortage of affordable housing.

The report also acknowledges that some research on four-day weeks is mixed, and more research is needed. Some studies have found the schedule helps retain teachers, reduce bullying, and boost attendance. Others link the schedule to reduced graduation rates, higher rates of food insecurity, and more chronic absenteeism among high schoolers.

Schoales said, “We stopped short of saying that folks shouldn’t do it, because we know that there are circumstances in which it makes sense.”

He cited remote districts where students may spend an hour or two a day on school buses.

“Those are rare instances relative to the state’s population,” he said.

While many school districts with four-day weeks offer enrichment programming or child care on the fifth day when there is no school, fewer families than expected use it, district officials told Keystone.

In Pueblo, Becky Medina, chief operations officer of the local Boys and Girls Club, worries about the children who aren’t showing up to the extra programming her clubs offer on Fridays.

“A lot of them don’t have the means. Whether transportation is the barrier or finances, they’re not getting those other experiences,” she told Keystone. “They’re the ones that are behind in school. Are they now falling farther behind?”

Because nobody tracks which students show up to fifth-day programming, “we’re pretty blind to that,” Schoales said. “It would make sense that kids with less are going to have a harder time taking advantage of that,” he said.

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.