Jasmine Baker says she’s probably the biggest patriot she knows.

“My patriotism isn’t found in an exuberant flag collection, or how many times I type ‘Merica’ in online debates,” she said. “The truth is, I don’t engage in either one of those activities.”

Instead, Baker teaches eighth grade U.S. history at Mrachek Middle School in Aurora, Colorado. There, she seeks to help students understand the nation’s founding, the vision that drove it, and the work that still needs to be done to realize its ideals.

Baker recently won a James Madison Fellowship from the James Madison Memorial Fellowship Foundation in Alexandria, Virginia. She’ll use the award, which pays for graduate coursework, to work toward her master’s degree in political science at the University of Colorado Denver and take a summer course on American Constitutionalism at Georgetown University.

Baker talked to Chalkbeat about how her time in the Air Force influenced her approach to teaching, why an annual scavenger hunt gives her hope, and what she does to get students excited about the Declaration of Independence.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

By the time I was in eighth grade, I knew I would be a social studies teacher. My eighth grade geography teacher, Mr. Granger, would allow me to complete the daily geography question by standing in front of the class and calling on other students to help me answer the prompt. I’m sure it was super annoying for the other students, but no one volunteered, and I was highly engaged in class. That year, I realized I could hold my own while teaching eighth graders.

How did your experience in the military influence your approach to teaching?

One of the Air Force’s core values is “excellence in all we do.” This value encourages me to rise to challenges in my profession diligently. I have a high standard for myself because I know I can — and do — excel in my profession. This leads me to have high expectations for my students because, with the proper support, they can rise, engage, and learn at a high level.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

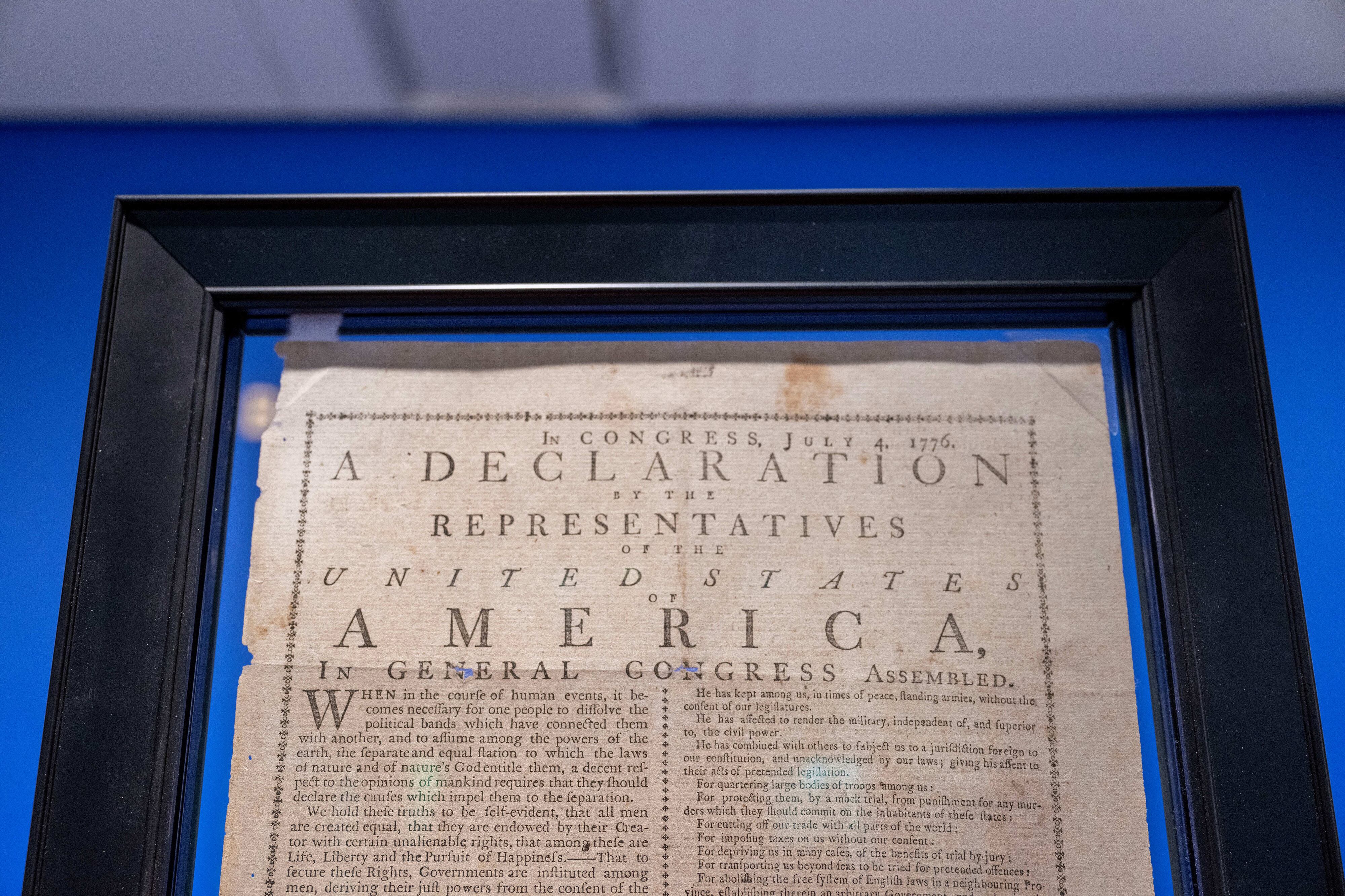

I thoroughly enjoy it when my students analyze the Declaration of Independence. The lesson starts with an engaging hook — a modern-day breakup letter the students believe is from one of their peers. It really draws the students in because who doesn’t like drama? The letter mirrors sections of the Declaration of Independence and is simply signed “A.C.”

I have to sell the letter and stay mum as they try to figure out which one of their classmates wrote it. Finally, I reveal the letter is from the American Colonists (A.C.). The students are so angry, but I’m able to channel that energy and excitement into processing the actual document. The magic is in the brilliance of the document and students realizing we have work to do to make those ideas actualized for all Americans.

What prompted your interest in the James Madison Fellowship and your desire to further study the Constitution and the nation’s founding.

I firmly believe that America has the potential to live up to who and what we claim to be, and those ideals are in our founding documents. After studying Americans’ behavior patterns and overall civic engagement, there’s concern for the democratic republic. One of the best ways to rectify an issue is through education. The James Madison Foundation provides a fantastic opportunity for teachers to deepen their understanding, craft, and skills so that we can better prepare the future of America — our students.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

Sometimes I feel frustrated by what I perceive as a lack of family engagement. However, every year that I have hosted the eighth grade Downtown Denver Scavenger Hunt, 25 to 35 parents come in to help us.

During the hunt, students are required to take at least one professional tour at History Colorado, Colorado Supreme Court, Colorado State Capitol, Denver Mint, Denver Art Museum, or Union Station. They must also find institutions, artifacts, individuals (we’ve met a couple of state representatives) that are instrumental in spreading culture and ideas, and in the administrative running of our society. Everything is worth points, so there is a winning team.

Family life for many of my students is complex, and there are barriers that parents have to overcome. So when that frustration creeps in, I remind myself of how parents in the community show up when I ask them to guide a group of four students around Denver.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on in your classroom?

The classroom is a microcosm of several communities. Their strengths appear in the classroom, as do the challenges. The strengths are diversity and support. We have students who are refugees and others who are new arrivals to American customs and culture, so it’s humbling to watch them show each other how to use Chromebooks and navigate classroom tools.

Although the community has many strengths, there is a lack of resources. Parents work hard, but sometimes they battle economic hardships. There’s a lack of a strong support system or “village” to help meet the needs of families. Also, there are unprecedented youth mental health struggles parents have to navigate.

What are you reading for enjoyment?

At the moment, I’m loving Manisha Sinha’s ”The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic.” She places Reconstruction from 1860-1920, which includes women’s suffrage. Like, duh! It totally makes sense, whereas most historians end Reconstruction around 1877 or so. Sinha lays out several points that illustrate how different sections of society attempted to rebuild America during and after the Civil War with the aim of what W.E.B. De Bois called “abolition democracy.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.