Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Before school started at her northern Colorado high school, senior Madison Vella heard complaints about the new rules barring cell phone use during class.

“A lot of students were like, ‘This is stupid. We’re almost adults,’” she said.

The rule change took some getting used to, but it’s been a positive, said Vella, a senior at Greeley West High School. Students are participating in class more and there’s a greater sense of community, she said.

Vella’s school district, Greeley-Evans District 6, is one of several in Colorado that have recently adopted new rules on student cell phone use. The crackdown comes as a growing chorus of educators and experts say cell phones are a major problem in the nation’s schools — distracting students, hindering their learning, and harming their mental health.

Officials in the Brighton-based District 27J adopted a tougher policy last year to make schools safer and give students a break from constant social media input, said Jaime White, the district’s executive director of safety, health, student support, and high schools. Before that, students would sometimes use their phones during class to organize fights, leading to physical altercations just moments after students were dismissed, she said.

During a meeting on 27J’s no-phone policy, Principal Krista Dean recounted an eighth grader at Stuart Middle School in Commerce City, saying: “I feel like I can breathe without them.”

A Chalkbeat survey of the 20 largest school districts in Colorado, found that District 27J is among six that have adopted stricter cell phone policies in the last two years. The others are District 49, Mesa County Valley District 51, Littleton, Pueblo 70, and Colorado Springs 11, where middle and high school students are required to store phones in locking pouches.

Other districts have tackled cell phone restrictions in other ways. Greeley-Evans officials announced new rules in a letter to parents earlier this month and plan to officially revise district policy later this year. The Poudre district, based in Fort Collins, also sent out a parent letter this month, informing elementary and middle school parents that its policy barring most cell phone use during the school day would be enforced this year.

Spokespeople for two other districts — Boulder Valley and Adams 12 — said district leaders plan to revisit their cell phone policies this year.

A teacher tried autonomy. It didn’t work.

Jeffco, the state’s second largest school district, is among six large districts that have no district-level cell phone policy. Teachers and schools set their own rules.

Starting this week, cell phones are the admission ticket students will hand over as they enter John Gallup’s history and government classes at Arvada West High School. The phones will sit in a clear plastic box that Gallup jokingly calls “phone jail.” (His daughter, a recent high school graduate, plans to decorate the box and rename it “phone vacation.”)

It’s a different tack than what Gallup took over the last two years. His idea was to treat students — most of them seniors — like young adults and let them handle phone use as they saw fit.

“To be perfectly honest,” he said, that approach was “a total failure because the kids could not check themselves. They just couldn’t.”

During an average class, three-quarters of students would continuously check their phones when they buzzed with a text or notification, he said.

A surprising number of students know it’s a problem, he said. On a get-to-know-you survey Gallup gives early on, several students typically say they want to spend less time on their phones or tackle their social media addiction.

Gallup said he’d prefer a simple, straightforward district cell phone policy — something like, students can’t have cell phones on their person in the classroom.

Students have wide-ranging opinions on cell phones at school

Vella, the Greeley West student, said before the district clamped down on cell phone use, she often saw students texting or scrolling Instagram or TikTok during class.

“If there was a dead moment in the class, instantly, students would kind of just like, get their phones out,” she said.

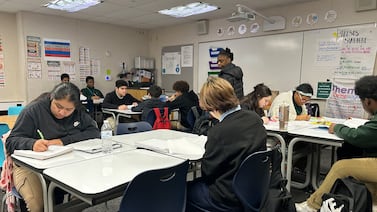

Now, most of her teachers give a general reminder at the beginning of class to put phones away and “de-bud” — a request to remove earphones. One offers a quarter point of extra credit every day students park their phones in the “phone garage” — a set of hanging phone pockets.

For the most part, students abide by the new rules, Vella said.

“It’s gotten a lot better and there’s more talking amongst the students … talking about the class itself or other things going on at the school,” she said.

Luka Nieto, a junior at Lakewood High School in the Jeffco district, doesn’t think a uniform cell phone policy is necessary. He said the rules should be up to individual teachers and match their teaching styles. He noted that his English teacher, whose class he loves, has a strict bell-to-bell no phone policy, but other teachers are more laid-back and allow students to be on phones occasionally.

An overarching cell phone policy would probably meet the same fate as his school’s stricter dress code rules from a few years ago, Nieto said. Students mostly ignored them and dressed the way they wanted to.

“It just got to the point where the school pretty much stopped enforcing it,” Nieto said.

Parents want to stay connected

Some parents worry that restricting cell phones at school will sever their access in case of emergency, though administrators also worry that parent-child text messages can sometimes spread rumors and disinformation.

Anthony Asmus, an assistant superintendent in Greeley-Evans, said some parents like to track their child’s location via cell phone. But since students’ phones can stay on during the school day, that’s still possible even under new rules.

Asmus said a few parents have also raised concerns about students who track medical issues using their phones — for example, with an app that notifies them if blood sugar levels are out of whack. He said the district will work with families in such cases.

Some educators say parents are among the biggest offenders when it comes to triggering student cell phone use.

“Kids will tell us — and do all the time — that it’s their parents texting, it’s their parents calling,” said White, of District 27J. “We have a generation of parents and kids who’ve always had cell phones.”

Sometimes parents share logistical updates, that they’ll be late for school pick-up, for example. But there’s plenty of trivial communication, too.

Gallup, the Jeffco history teacher, said when he’s asked students who they are texting mid-class, he’s heard things like, “Oh my mom … My sister forgot to feed the cat.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.