Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

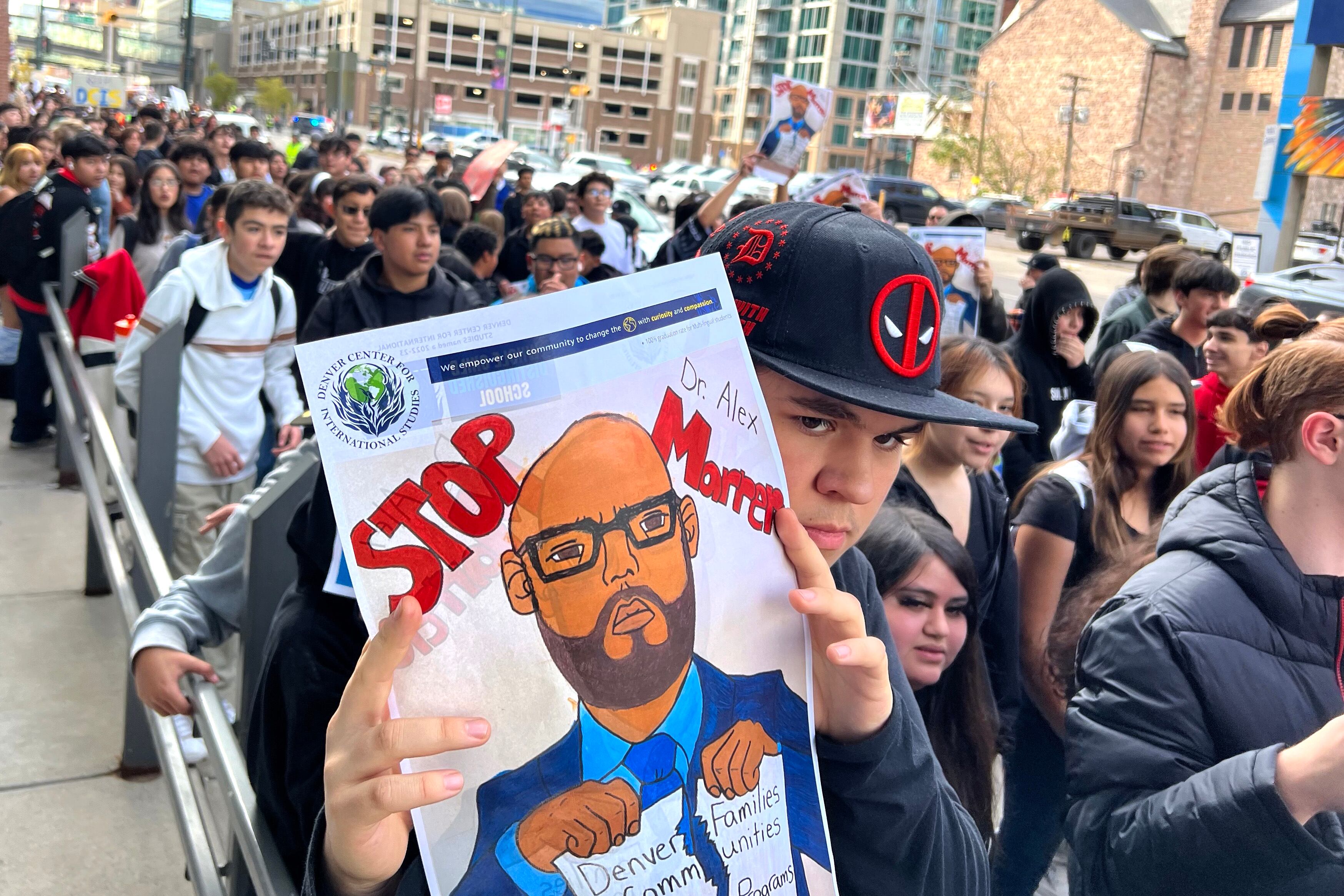

After a week of attending meetings and waiting to be called on to speak, of making impassioned pleas and wiping their eyes with tissues supplied by the school district, hundreds of Denver students tried a different way Friday to express their opposition to a plan to close their schools.

Middle and high school students from three of the 10 small schools up for closure marched to Denver Public Schools headquarters. They stood on the sidewalk with homemade signs and borrowed bullhorns and let district officials know how they felt.

“Keep your hands!” they chanted. “Off our school!”

When three members of the Denver school board came out of the locked front doors and offered to meet with a small group of students, a senior named Camila from Denver Center for International Studies told the crowd they were making a difference.

“Our voices are being heard!” she said into a microphone as two classmates held an amplifier above their heads. “Our stories are making their mark!”

All week, students, parents, and teachers from the 10 schools have been trying to persuade school board members to reject a recommendation from Superintendent Alex Marrero meant to address declining enrollment in the district. The board is set to vote on Thursday.

After agreeing to a tight timeline with just two weeks between the recommendation and the vote, board members fanned out to the 10 schools. They held four meetings at each school, setting aside time to listen to families and educators in the morning, over the lunch hour, in the afternoon, and again in the evening. The packed schedule was an attempt to do a better job at community engagement than they did the last time Marrero recommended closing schools.

Under Marrero’s current recommendation, Castro Elementary, Columbian Elementary, Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, International Academy of Denver at Harrington, Palmer Elementary, Schmitt Elementary, and West Middle School would be closed.

Kunsmiller Creative Arts Academy, Dora Moore ECE-8 School, and Denver Center for International Studies would partially close, with each school losing some grades.

“We haven’t decided yet how we’ll vote,” board President Carrie Olson told a packed room at West Middle School on Friday. “That’s why we’re here today, to hear from you.”

What the board heard was frustration, anger, and sadness.

“Somos familia,” West mom Laura Reyes told board members in Spanish, pausing for the interpreter to say her words in English: “We’re family.” She pointed at her young son beside her.

“He has to come here,” she said.

‘We are splitting apart this community’

Students, parents, and teachers had similar concerns across the 10 schools. Students worried about losing trusted teachers and being separated from good friends.

Parents worried that their children would be lost at bigger schools — or, even worse, bullied.

Teachers worried about their jobs. Many also defended their schools as tight-knit communities where every educator knows every student and makes sure their needs are met.

“We don’t fit the narrative that gets spun about small schools, and we take that personally,” Schmitt Elementary Principal Jennifer Nelson told board members Tuesday.

That narrative, as explained by district officials, is that because Denver funds its schools per student, small schools don’t have enough money to offer robust programming. Schools with low enrollment may have to cut electives or combine classrooms.

At Schmitt, staff said that’s not the case. The school has a teacher and a paraprofessional in every classroom, bilingual programming, and a mental health team. But at 127 students, Schmitt also received more than $430,000 in small school subsidies from the district this year, according to district data, which accounted for about 12% of Schmitt’s budget.

Nelson said that while she would love for the school to stay open — ”The only way to get me out of this school is to kick me out because my heart lives here,” she told board members — she believes the district’s plan for Schmitt students is better it was two years ago, when the district proposed closing Schmitt and reassigning all of the students to one nearby school.

This time, families would be encouraged to choose from among three schools.

“I do want to acknowledge the equity that’s being offered this time is better than in the past,” she said to a room full of frustrated parents and teachers. “Two of the schools are very good schools. We’re getting an offer for transportation to any of the three schools. I appreciate that as someone who loves your children not just today but all their lives.”

At other schools, some teachers and parents acknowledged that declining enrollment has led to cuts in staff and programming. Still, they’re not happy with the district’s proposed solution.

For example, half of Castro Elementary’s students would be reassigned to one nearby school and half the students would be reassigned to another. One of the nearby schools, CMS Community School, is a dual language school that teaches students in both English and Spanish. While nearly all of Castro’s students are Latino, not all of them speak Spanish.

“I do think we are splitting apart this community, which is one of the tough parts here,” said Kaylee Keuthan, the social worker at Castro. “The splitting up is creating even more unpredictability and instability with kids who already deal with that.”

Students ask: ‘Please do not shut us down’

For some students, this is their second time being faced with school closure. A junior named Joy said she came to Denver Center for International Studies after her charter school, American Indian Academy of Denver, closed in the spring of 2023. Indigenous students, she said, found a new home at DCIS, which hosts cultural events and teaches indigenous languages.

“DCIS welcomed me with open arms when I was looking for another school,” she told board members Thursday. “I wish you all would actually care.”

Students at DCIS have proposed a plan for their 210-student high school to share space with Denver School of Innovation and Sustainable Design, an even smaller high school with just 60 students that has become a safe space for LGBTQ and neurodiverse learners.

Elementary and middle school students also spoke out against the potential closures. On Wednesday, Castro Elementary’s fifth graders took turns addressing the board.

“Castro is the only school I am able to walk to from home,” said a fifth-grader named Angelina. “Castro is a really great school. Please do not shut us down.”

“Not that many schools have a therapist dog, and that means Castro is a school that cares a lot about students’ mental health,” fifth-grader Elyssa said about Castro’s new therapy dog named Silver. “Where would she go if you shut down Castro?”

“We are just kids,” said fifth-grader Analizeth. “We should not have to worry about these things.”

Castro parent Ana Mejia said her children had been crying for days.

“My daughter has cried herself to sleep,” Mejia said. “We live in an ugly world. There’s bullying at every school. How is she going to make new friends? Have a heart. Think about the kids.”

Dalia Miranda, who has three children at Schmitt, was also concerned about bullying. She told board members Tuesday that closing trusted schools and sending children into unfamiliar environments is like “sending new victims to schools where bullying exists.”

Miranda also asked why the district recently upgraded the Schmitt building — pouring more than $1 million into a new elevator, new paint and furniture, and other projects this past summer — if the superintendent was going to recommend the school be closed. The money came from a $795 million bond measure approved by Denver voters in 2020.

“We’re all committed to, as long as a building is open, we’re going to push in and give it what it needs,” said board member Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán. “If the school closes, it won’t remain vacant.”

Parents question district data

While some parents tried to appeal to school board members’ hearts, others attempted to change their minds with data, interrogating the district’s enrollment numbers and accusing officials of misrepresenting data or being shortsighted in their projections.

Parents pointed to new housing developments, some with five-bedroom apartments for families. But district officials said those new families aren’t enough to make up for enrollment losses caused by declining birth rates and rising housing costs pricing many families out of the city.

A neighbor at Castro said he sees school buses stop at nearby houses, picking up children to take them to other schools. Why couldn’t the children come to Castro instead? he asked.

The children could come to Castro, Gaytán told him. But their families are choosing other schools, as allowed under state law. Data shows about 42% of the district’s 90,000 students attend a school that is not their neighborhood boundary school.

“We can’t control and force them to come here,” Gaytán said. “They are choosing other schools.”

Gaytán didn’t mince words this week in expressing her opinion that part of the problem is that the district allowed too many charter schools to open in southwest Denver, “siphoning and taking away our children.” Parents and teachers often applauded after she said it.

“My district — southwest Denver — has been over charter-ized and I don’t appreciate that at all because look at where we are now,” Gaytán told teachers at Castro on Wednesday.

Other board members pointed out that while many charter schools opened in Denver over the past few decades, many have closed, too. Twelve Denver charter schools have closed since 2019, often due to declining enrollment, including in southwest Denver.

School choice came up again Thursday night at Palmer Elementary in near northeast Denver. Palmer was on a previous closure list in 2022. Although the school was spared, parents said the near-closure caused many neighborhood families to choose other schools. District data shows that 146 students “choiced out” of Palmer in 2021. This year, that number rose to 180.

Preschool teacher Emily Bovard tearfully asked the board to help Palmer reverse that trend.

“Help us shed that scarlet letter that has been placed on our school,” she said. “Help us stay special.”

At a meeting at Palmer earlier that day, a teacher asked what would happen to the building if the school closes, a common question from both families and educators.

Board President Olson gave the same answer she’d given all week, one that the board wrote into its policy: that the superintendent “comes back to you and talks to you about what you want to see and the community wants to see happen to the Palmer building.”

“A school,” someone murmured.

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.