Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

In room 126 at Denver’s South High School, students in a Spanish language arts class got suggestions for improving their short essays from an artificial intelligence app called Magic School: “You could elaborate on your examples,” the app advised one student.

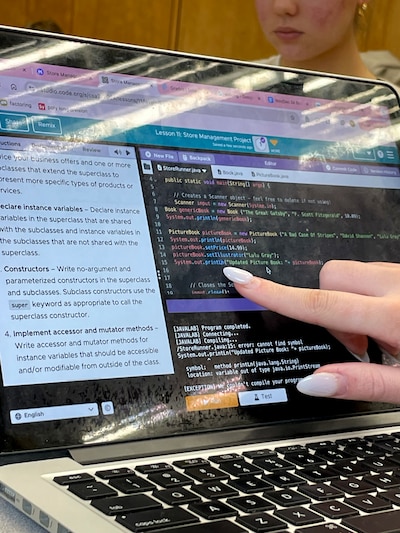

Upstairs, in AP Computer Science, a student shared the fix she made after feeding the Java code she’d written for a bookstore inventory system into the same AI app.

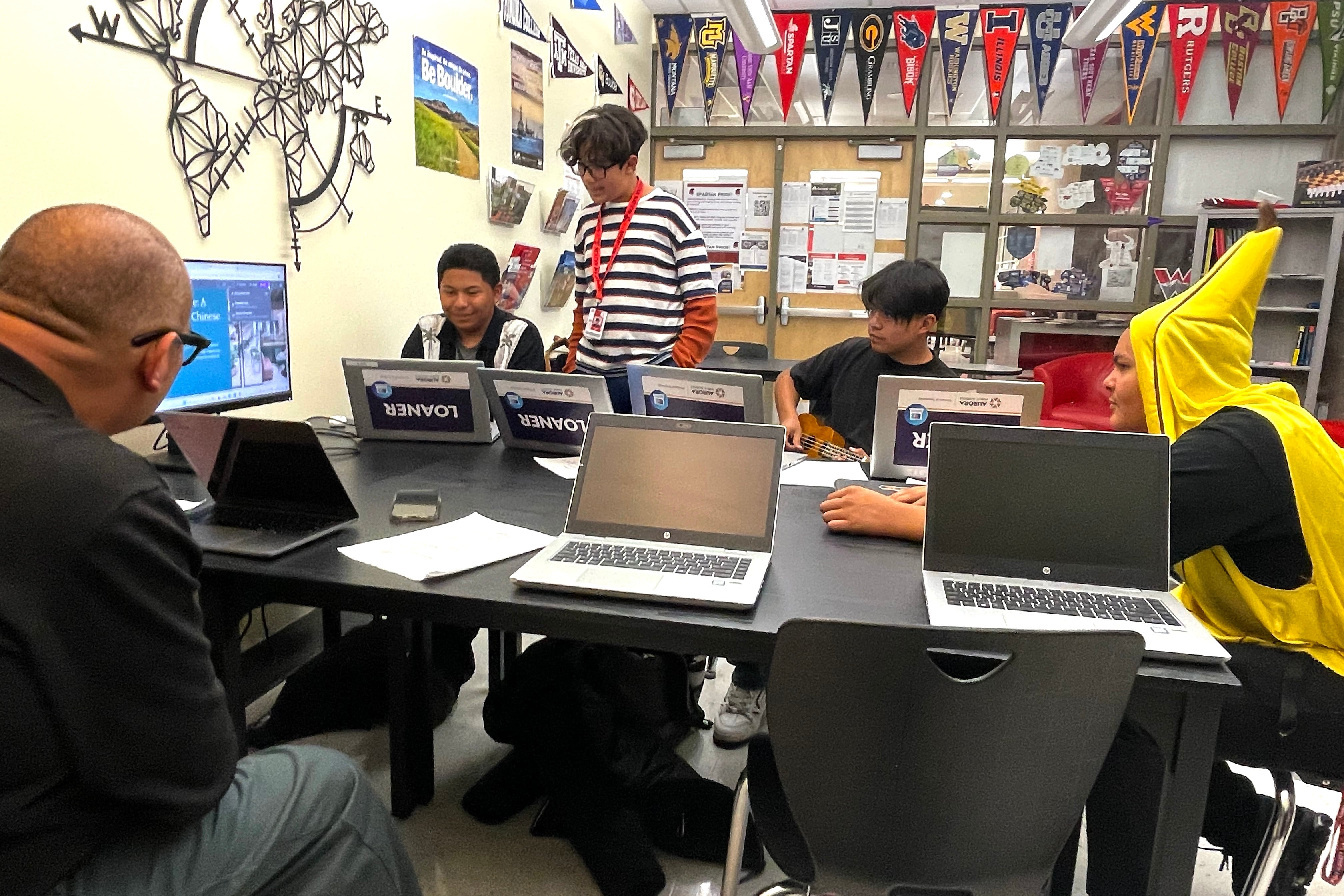

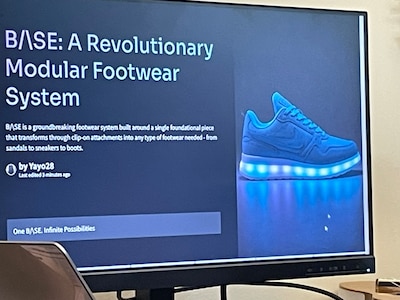

Later that October day, students in an after-school club at Aurora West College Preparatory Academy pitched hypothetical products in presentations augmented with AI images and text.

For A’mariae, a ninth grader who envisioned a high-tech shoe that could be transformed from sandals to sneakers to boots with clip-on attachments, there was one problem. The trendy blue shoe the AI app had conjured on his laptop screen had a Nike swoosh on the side, a trademarked logo that would be off-limits for his brand.

These scenes illustrate how Colorado teachers and students are beginning to use artificial intelligence in the classroom — and navigate its limitations. Since ChatGPT burst onto the scene in late 2022, the use of generative AI in schools in the state and across the country has become increasingly common. New York City’s schools chief championed the use of AI before he left the post in October, and districts in New Jersey and Indiana are piloting AI tools.

Generative AI analyzes huge amounts of data to generate text, images, videos, and other kinds of content.

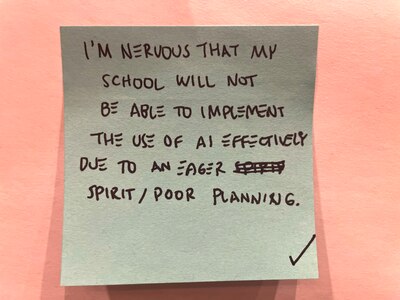

For the moment, many teachers, and students are approaching AI more as a toe-dipping exercise than a plunge into the deep end. Not only does it take time to test and learn the apps, they don’t always work as intended. In addition, some districts are still figuring out what guardrails need to be in place to protect student privacy.

Still, the sense of excitement about AI in education is real, with a flood of products on the market and a complementary stream of AI conferences, training, and webinars available to K-12 educators. Currently, eight districts in Colorado, ranging from Adams 12 to Estes Park to Durango, are participating in a yearlong project to build AI literacy offered through the Colorado Education Initiative, which has taken a leading role in ushering the state’s schools into the AI age.

Karen Quanbeck, vice president of statewide partnerships for the organization, ticked off some of the ways AI can help teachers: quickly adapting passages for students at different reading levels, providing personalized tutoring after school hours, and allowing students to have a conversation with a computer facsimile of a historical figure.

“My goodness, just the potential for what this could do, for closing learning gaps, for really helping us rethink how learning experiences look because the ‘stand-and-deliver’ model is not always effective,” said Quanback.

Jeff Buck, the AP Computer Science teacher at South and a 26-year veteran of Denver Public Schools, recently joined a different yearlong AI training program for educators. He’s also taking a series of AI trainings offered by his district.

“This is what keeps me going. I can learn something new and interesting, right? And kids are kind of interested, and so we’re learning together, and I think that’s really fun,” he said.

But the learning curve, he said with a laugh, is “also a massive time sink.”

AI can be a time-saver but accuracy is ‘not 100%’

Once teachers master the apps, AI can be a time-saver, helping draft lesson plans and tests, taking a first pass at grading essays, or writing and translating parent newsletters. The cost of the apps varies, with basic versions often available for free.

Moisés Sánchez Bermúdez, the South High School teacher whose students used Magic School to get writing feedback, said he’s generally been impressed with app’s suggestions. Even its critiques of student poetry were decent.

“It was not 100% but it’s getting there,” he said.

By using the app to give students — sometimes up to 35 in the classroom — immediate feedback on their first drafts, Sánchez Bermúdez has more time to work with students individually.

“It gives them meaningful work to do while I go one by one,” he said.

But not everyone likes getting pointers from a chatbot.

“I don’t really like using AI for the feedback. I’d rather have a real person,” said Juliana Gutierrez, a junior in Spanish Language Arts 3. “If you don’t understand something, you can ask [the teacher] to explain it in another way, or in more of a personal way.”

One floor up, Buck recalled how he’d given his students the option to ask Magic School to review their Java code.

The response was “tepid,” he said. “Not everybody is necessarily seeing the value right now.”

While most students chose to ask Buck or classmates for feedback, a few students used Magic School. One of them was Mimi Genter, a senior who’d written code for organizing book store inventory.

The app returned a neatly organized list of the things she’d done correctly, signified by green checkmarks. It also flagged a typo in her code, suggested an additional feature she could add, and closed by saying, “Keep up the excellent work. You’re really grasping these object-oriented programming concepts.”

Genter said it was only the second time she’d used Magic School but appreciated that it was an efficient fine-tooth comb of sorts — instantly spotting a capital “L” that should have been lower-case.

Helping students understand the AI landscape

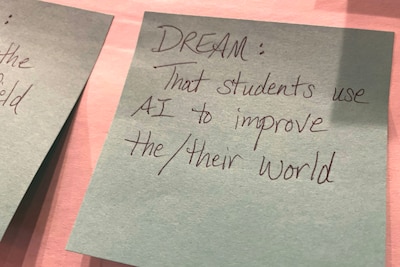

As educators incorporate AI tools into their lessons, many are looking not only to make lessons enriching, but to build students’ fluency in a technology that’s here to stay.

They want students to understand how to craft prompts that return worthwhile information, to use AI tools to deepen learning without crossing the line to cheating, and to recognize the inherent weaknesses of artificial intelligence.

Talley Nichols, who teaches high school history at Crested Butte Community School in western Colorado, sent out permission slips last spring asking parents if their children could use ChatGPT in class. She was pleasantly surprised by the response.

“I was worried about parental pushback, but I didn’t get any,” she said. “In fact, I got a couple of parents who were like, ‘Thank you for doing this. This is important. They need to learn how to use this.’”

Nichols said her students like using AI to generate project or topic ideas: “It’s really good at giving you lists of ideas, and then you can take that and run with it.”

But she’s proceeding with caution. When her students did research projects last spring on key figures from European cultural movements like the Renaissance, she had them print out the responses they got from ChatGPT, evaluate the quality of the responses, and then seek out other non-AI sources for further research. And when Nichols’ students turn in final essays or projects that incorporate AI, they have to turn in notes, rough drafts, and edits to prove they’ve done the work every step of the way.

“If there’s something that they could just go home and create on ChatGPT, I don’t make that a homework assignment,” said Nichols. “We do that in class.”

Educators are also helping students think critically about the racial and gender bias inherent in AI.

Students in Aurora West College Preparatory Academy’s weekly after-school club, “AI Studio” quickly discovered that predisposition as they experimented with AI this fall in preparation for their marketing presentations. When A’mariae asked the tool to produce images of doctors, it showed two older white men and one white woman. When he asked for an image of “three white teenagers,” he got a picture of three happy white teenagers.

Next, he said, “I searched three black teenagers and it showed, like a mug shot.”

Asked how to deal with racist and sexist results, one of the other three boys in the club said, “You have to train your AI.”

It’s exactly the message Antonio Vigil, Aurora’s director of innovative classroom technology and the club’s advisor, has been emphasizing all semester. He wants students to understand that they have to continually vet AI responses for accuracy, precision, and bias – and revise them accordingly.

He said, “You have to be the human in the loop.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.