Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

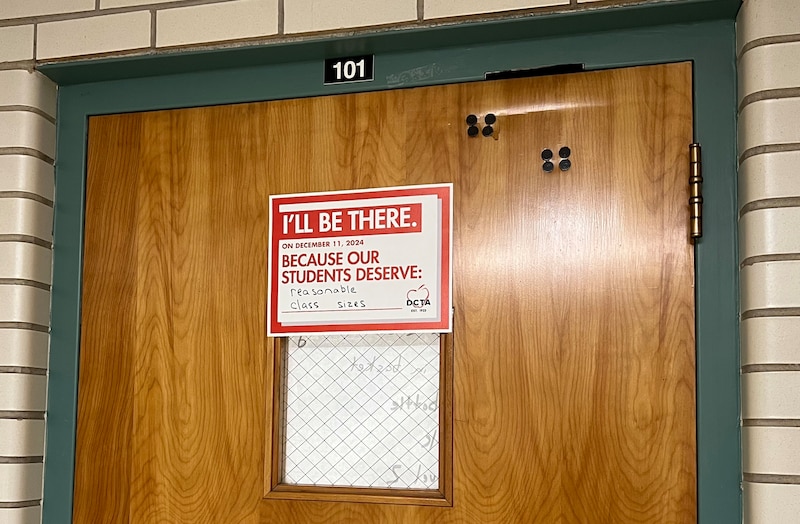

Smaller class sizes will be one of the Denver teachers union’s top priorities when it begins negotiating its next contract with Denver Public Schools this year.

Aside from the ever-present issue of teacher pay, class size caps are top-of-mind for many teachers as they grapple with how to catch students up from pandemic learning losses, reverse troubling absenteeism trends, and attend to students’ increasingly complex mental health needs, union leaders said.

Class size caps haven’t changed in Denver since 1994, when the union went on strike and the district agreed to a cap of 35 students, among other issues.

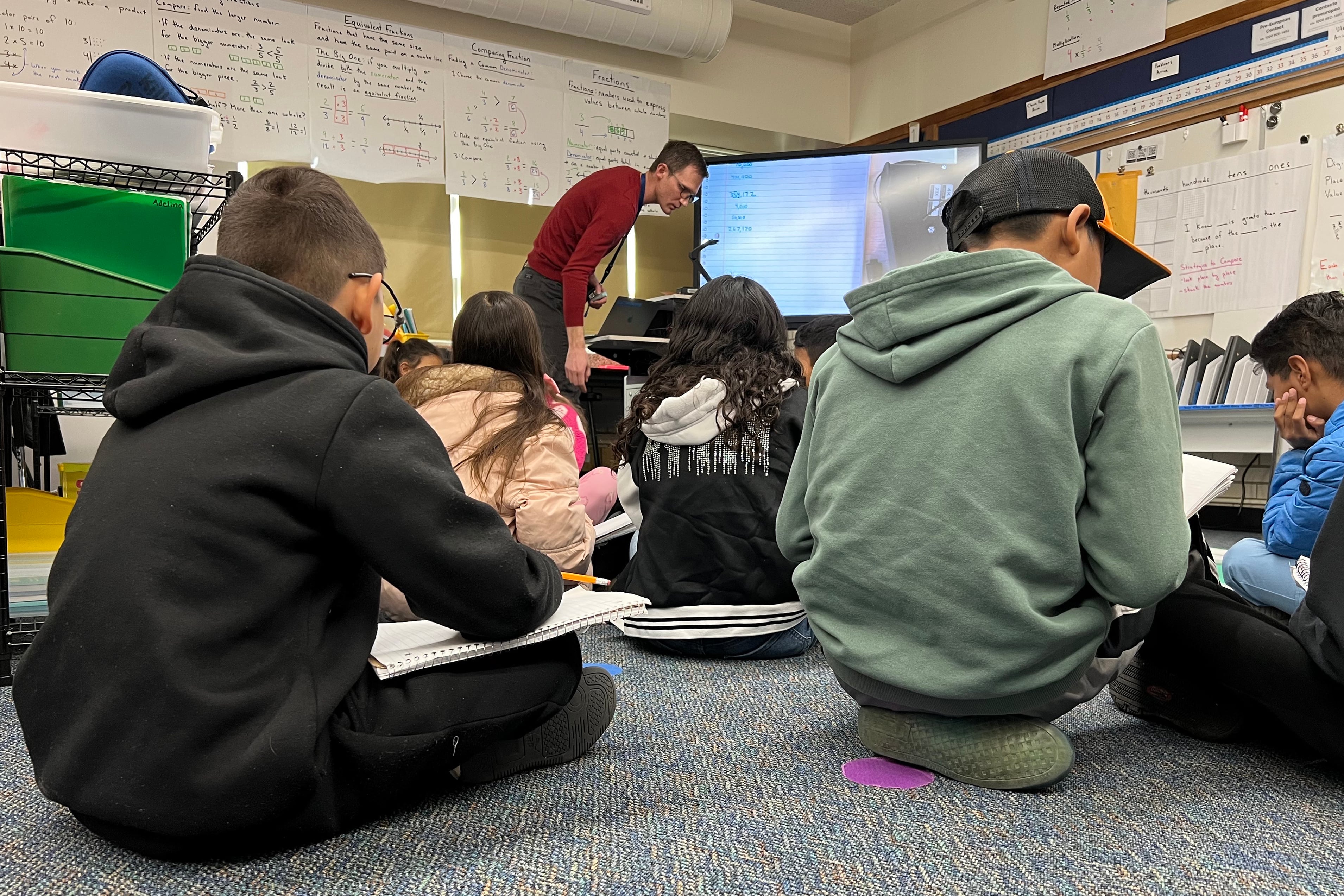

One of the concerned teachers is Matt Meyer, who teaches fourth grade at Denver Green School Southeast. Some classes at his school have swelled to the maximum capacity of 35 students due to an influx of migrant students from Venezuela and other countries.

Meyer’s classroom is both cheerful and bursting at the seams. Walking through it can feel like navigating a minefield of puffy coats and Minecraft backpacks hanging from the backs of chairs. His classroom door is constantly swinging open, its squeaky hinges announcing the arrival of another student coming back from the bathroom or leaving for a specialized learning group.

His 9- and 10-year-old students are still young enough to skip rather than walk back to their seats, but old enough that they take up a considerable amount of room. As the students worked at their desks on a recent Monday, one girl accidentally invaded another’s personal bubble.

“I know there’s not a lot of space in here,” Meyer said to the girl. “Are you okay to keep working here for a bit or do you want to find another spot?”

“Find another spot,” she said.

He directed her to a lone empty desk at the front of the classroom that was sandwiched between a Chromebook charging rack and a rolling cart full of lunch boxes.

“She came from another DPS school with 22 kids in a classroom,” Meyer said later of the girl. “I can have her go sit by herself, but then she’s by herself.”

That’s contrary to the way Meyer likes to teach.

“At DGS, we are all about hands-on learning,” he said. “Last week, we pulled out Base 10 blocks. Kids learn best when they are doing hands-on activities and talking to each other in collaborative groups. It’s hard to do that with as many kids in our room.”

Denver Public Schools declined an interview request for this story. But in written answers to questions from Chalkbeat, a district spokesperson said that class size is a concern, but “that lower class sizes are often correlated with an increase in staffing, so we need to be cognizant of that while balancing a shrinking budget.”

School districts’ state funding is based on student enrollment. Despite the recent enrollment boosts from migrant students, Denver is predicting a 9% decline in enrollment by 2028.

Asked if the district would be open to lowering the class size cap, the spokesperson wrote that “DPS is open to discussing any ideas that would be beneficial to improving student outcomes.”

The current three-year contract between the teachers union and the district is set to expire on Aug. 31. Union leaders said they hope to start negotiations next month. A district spokesperson said representatives from both sides will meet next week to discuss meeting details.

Denver’s average class size is far below 35 students

Documents obtained by Chalkbeat in an open records request show that the average elementary class size in Denver last school year was 23 students, far below the 35-student cap.

But about 38% of elementary classrooms had more than 25 students, according to the documents. Per the current contract, those classrooms are entitled to receive between one and three hours of support per day from a paraprofessional, depending on the class size. About 9% of elementary classrooms had 30 students or more.

The average middle school class size last school year was 23 students, the documents say. The average high school class size was lower at 19 students.

But 28% of middle school core classes and 20% of high school core classes had 30 students or more. English, math, social studies, and science are considered by DPS to be core classes.

Leaders with the Denver Classroom Teachers Association said in interviews that if the majority of DPS class sizes are indeed that low, the district shouldn’t oppose lowering the class size cap to a number the union sees as more manageable, such as between 20 and 25 students.

“If it’s true that the majority of schools have these lower class sizes, then it shouldn’t be a problem to lower those class size limits,” said union President Rob Gould.

Brian Weaver, a sixth grade teacher and co-chair of the union’s bargaining team, said that even if only 20% of classes are above 30 students, “that’s still a lot of teachers and still a lot of students that are experiencing this overloaded class size.” DPS serves about 90,000 students.

Weaver said the current solution for large elementary class sizes — paraprofessional support — can be hard to come by, especially if class sizes increase mid-year. Weaver said he has had classes that started with 26 students and ended with 34.

“Getting paras mid year is almost impossible,” Weaver said. “The admin says, ‘Hey, I’m looking for a para and nobody is applying,’ but you still have this class size that is unmanageable.”

Middle and high school teachers with larger class sizes don’t get the same type of paraprofessional support under the current contract. Instead, the contract specifies that no secondary teacher should teach more than 175 students per day.

New York City has a law governing class size that caps kindergarten to third grade classes at 20 students, fourth to eighth grade classes at 23, and high school classes at 25. Colorado has no such law. Here, policies and union contracts differ from district to district.

Some union contracts in Colorado have concrete class size caps. Others don’t. Among the ones that do, Aurora Public Schools’ caps are lower than Denver’s caps. In Aurora, kindergarten and first grade classes over 22 students, second and third grade classes over 25, fourth through eighth grade classes over 30, and high school classes over 32 warrant a review.

“We know there are only so many hours in the day, and when it comes to student needs, we want to be able to focus on our kids,” said Michelle Horwitz, a bilingual speech language pathologist and co-chair of the Denver union bargaining team. “When classes are upwards of 30 or 35 kids, the individualized instruction and one-on-one isn’t happening.”

In addition to smaller class sizes, the union’s bargaining priorities include competitive teacher pay and benefits, sustainable caseloads for special education service providers, educator rights, and making sure Denver schools are safe and welcoming, union leaders said.

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.