Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

A middle school administrator who was fired by the Elizabeth School District after calling a plan to remove school library books racist has filed a civil rights complaint with both the state and federal government.

LeEllen Condry, a former dean of students at Elizabeth Middle School, alleged discrimination and retaliation by the district in complaints filed Wednesday by her lawyer with the Colorado Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Condry, who is Black, said she wrote a letter to the school board last August protesting the district’s plan to remove a number of books from the school libraries in the district.

“I basically said that it was unethical, it was racist,” she said in an interview Wednesday.

She was terminated on Oct. 1, 2024.

Condry’s civil rights complaint is the latest fallout from the Elizabeth district’s decision to remove 19 books from school libraries this school year because of what the school board deemed highly sensitive content. In December, the American Civil Liberties Union sued the district on behalf of two students and two groups, arguing that the book removals violate federal and state free speech protections.

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. Department of Education announced this month it would end investigations of schools that removed books from their libraries.

Condry’s lawyer, Andy McNulty, said the complaints are the first step before a lawsuit can be filed. He estimated it will take six months for the Colorado Civil Rights Division, the lead agency in the investigation, to issue a decision. At that point, he plans to file a lawsuit on Condry’s behalf that will include discrimination and violation of free speech claims.

McNulty said he doesn’t have a copy of Condry’s letter to the school board, but has been working to get one from the school district for months. He said the letter was on Condry’s work computer, but she had to turn that in when she was terminated.

Jeff Maher, a spokesperson for the Elizabeth School District, said by email on Wednesday morning that district officials have not yet seen a copy of Condry’s complaint. He also said they would not comment on personnel matters.

Elizabeth is a 2,700-student district about 30 miles southeast of Denver.

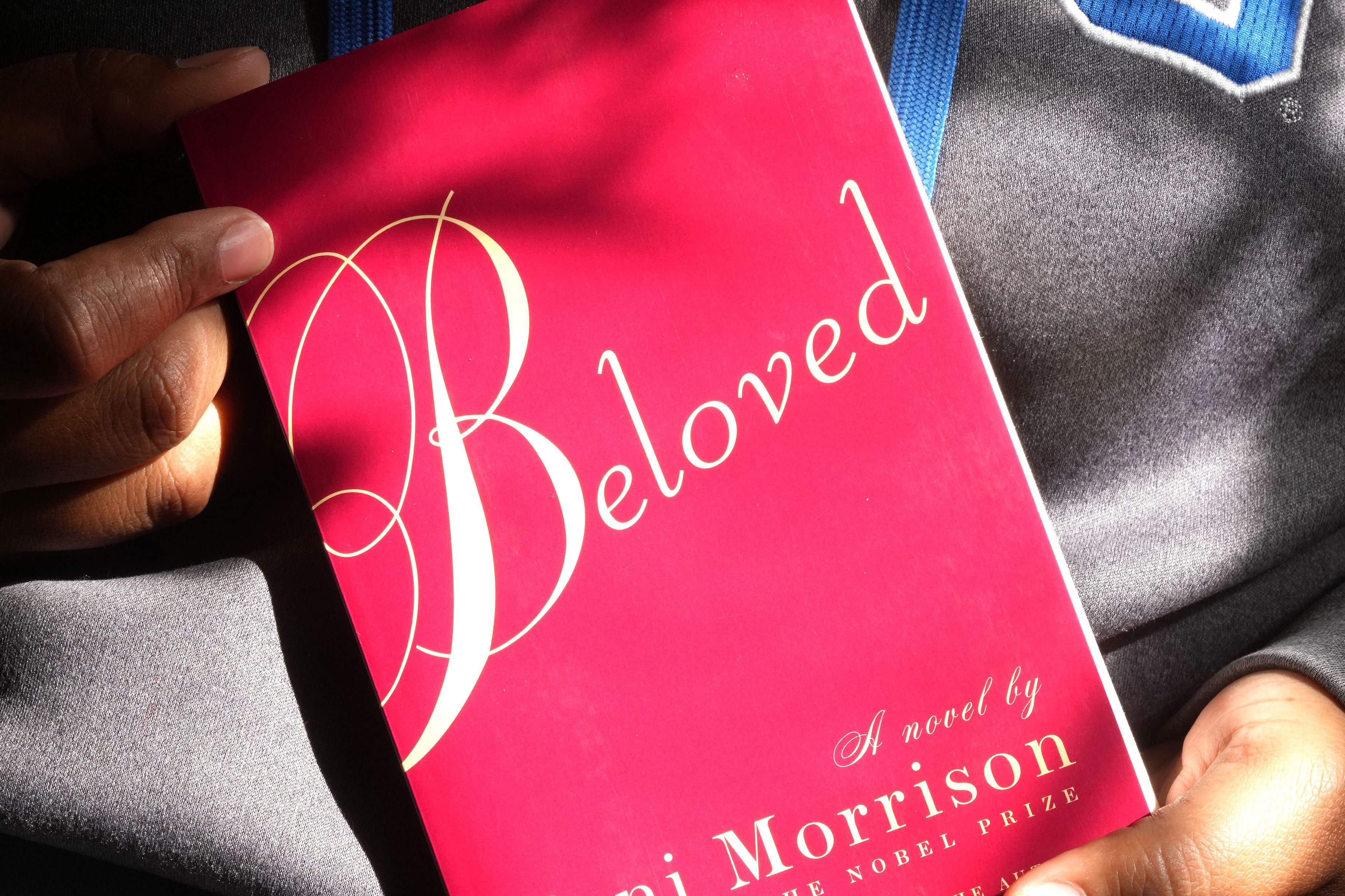

The 19 books removed from school libraries in the district are primarily by or about people of color, LGBTQ people, or both. They include “The Bluest Eye” and “Beloved,” both by Toni Morrison, “The Hate U Give,” by Angie Thomas, and “You Should See Me in a Crown,” by Leah Johnson. All three authors are Black and their books feature Black characters.

The ACLU lawsuit notes that the removed books include discussions of same sex relationships, LGBTQ characters, racism, police violence, or other content Elizabeth school board members considered “disgusting.”

Dozens of other school library books weren’t removed but ended up on a “sensitive” list compiled by a curriculum review committee. Parents can prohibit their children from checking out books on the list, which include titles such as “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “The Hunger Games” and “Muslim Festivals Throughout the Year,” according to the lawsuit.

Condry’s civil rights complaint alleges that after she wrote the letter to the school board objecting to the proposed book removals, Superintendent Dan Snowberger sent an email to her and all other district staff.

According to the complaint, he wrote, “[s]adly, some staff members did seem to misunderstand the request [for feedback] and somehow felt the request was an opening for harsh feedback to the Board on their decision.”

The complaint goes on to say that Snowberger cited Condry’s feedback, saying that calling the board’s actions racist “crossed the lines of professional and ethical behavior.” He also said in the email that the feedback would lead to “further disciplinary action.”

Condry was called to meet with Snowberger, the district’s human resources director, and the Elizabeth Middle School principal on Oct. 1. She was told she was being terminated for budget reasons, according to the complaint.

Condry, who has not yet secured a replacement job, said many teachers and administrators were scared to share their objections about the book removals.

“It’s important that individuals such as myself, who is of Haitian American descent, speak out against what is happening in the district, especially with the book ban,” she said.

She said she did it for Black, Latino, LGBTQ, and immigrant students in the district.

“They need to be able to have books that they can self identify with,” she said. “I just feel that when those specific books are being removed, it removes our heritage, who we are as people, and I don’t want to see that happen.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org.