Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Last July, families at a Highlands Ranch child care center received startling news: The center was temporarily closing following a visit from the county health department.

The center’s owners failed to submit required construction plans to the Douglas County health department and get construction permits from the county’s building division.

A state child care licensing inspector also found several safety violations related to the construction: Emergency exits were blocked by tools and debris, and paint and construction materials were accessible to children.

A former teacher and a former aide at the center shared additional details with Chalkbeat. They said the center’s main security doors were propped open at times, allowing workers and others open access to the building. They found concrete chunks on the playground, and a child found a box cutter there on at least one occasion, as well, they said. The former staffers spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of career repercussions.

The renovation was the result of an ownership change: In early July, a national chain called The Nest Schools purchased the center from a small local company. The chain has six child care centers in Colorado — all of which opened after Detroit-based private equity firm Rockbridge Growth Equity invested in the company in 2022.

Some early childhood experts have recently sounded the alarm about the growing footprint of private equity in the child care space. They worry that such investment firms are primarily motivated by outsized profits, not providing quality experiences for young children. But others say private equity-backed child care is already providing many desperately needed seats and that its deep pockets can help a fragile industry during a challenging time.

Gerry Pastor, co-CEO of The Nest, said in an email that private equity investment helped sustain and grow The Nest Schools, including by making much-needed upgrades costing more than $1 million at the Highlands Ranch center.

He said that while the center tried to keep child care operations separate from construction, “a few unintended issues arose” that were corrected immediately. He said children, staff, and families did not use exterior grounds during construction there. He also said some of the allegations that Chalkbeat inquired about “never happened” but he didn’t specify which ones.

A Rockbridge spokesperson had no comment.

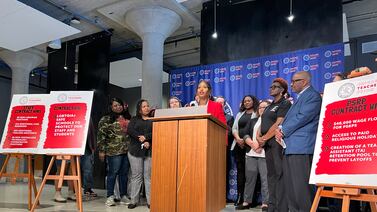

Colorado lawmakers are taking notice of private equity’s push into child care. In January, they introduced legislation that would put new limits on private-equity backed centers in an attempt to temper practices that critics say are harmful, including cutting staff and raising tuition. The bill would give the public more information about tuition and fees, provide advance notice of staff layoffs or enrollment changes, and curb a common private equity real-estate practice that can hurt child care centers financially.

“We just want to make sure that as more investors come to the state that they understand they’re coming to the state to invest in high quality [child] care and not simply just to turn a profit,” said state Rep. Lorena Garcia, a Democrat who is sponsoring the bill.

Experts say private equity firms often make swift changes when they invest in child care centers. At The Nest Highlands Ranch, those changes had consequences beyond physical upgrades. The director and assistant director quit within a month, according to letters The Nest sent to parents, and parents said around 10 more staff members also left.

Brooke Aldaz, whose two young children were enrolled at the center, told Chalkbeat she saw problems shortly after renovations on the decades-old building began. She said she became particularly alarmed when she, her 1-year-old son, and his visiting speech therapist were sent to meet in a classroom that had been closed for construction.

“There was broken glass and old dishes,” she said. “I remember being very uncomfortable that it was even suggested that a 1-year-old child should be in that room.”

The Highlands Ranch center reopened within a couple weeks but Aldaz said it was no longer the place she once considered “idyllic.”

Private equity prizes speed and profit, experts say

Private equity has long had a stake in all kinds of industries, from health care and autism services to rental housing. In recent years, its footprint has grown in the child care sector.

Private equity firms typically use a little of their own money plus loans and funding from big investors — often pension funds, endowments, and extremely wealthy individuals — to buy companies they aim to sell at a profit later.

Experts say one of the hallmarks of private equity is that the firms borrow lots of money to buy companies — debt that can strain the companies financially and increase the risk of default or bankruptcy. But chronic child care shortages make families captive customers who take whatever’s available.

Elliot Haspel, a senior fellow at the think tank Capita who’s written extensively about private equity in child care, said the private equity playbook prioritizes speed.

“The idea is that you want to sort of wring as much profit as you can, usually over three to seven years, and then you want to ditch it off to some other private equity firm,” he said. “There’s an incentive, plausibly, to go really fast.”

Private equity firms use various strategies to turn a profit, including cutting costs and raising prices. Many child care chains backed by such firms buy centers in affluent areas where parents can more easily shoulder tuition and fee hikes. Mom-and-pop child care owners may sell to child care chains because they are retiring or leaving the field.

A Chalkbeat analysis identified about 175 Colorado centers currently owned or backed by private equity or venture capital firms — representing about 15% of the state’s licensed child care capacity for young children. Most are large, with space for more than 100 children.

The state’s child care rating system – which considers factors ranging from staff credentials to certain business practices – shows that about 40% of those centers have one of the state’s top three ratings. By comparison, about 32% of all Colorado child care programs overall hold those top ratings.

While state ratings are a starting point for determining quality, they provide only a snapshot because they are awarded once every three years. Highly rated programs can still be cited by the state for violations, put on probation, or fined.

Some early childhood leaders believe private equity-backed centers are meeting a need and that more regulation, as proposed in Colorado, could be harmful.

“I think we want to be careful about implementing anything that is going to hurt an already distressed system,” said Nicole Riehl, president and CEO of the Colorado business-focused group Executives Partnering to Invest in Children. “It’s like paying attention to the nail that’s sticking out of the fence when the fence is laying on the ground.”

Other groups, ranging from the National Women’s Law Center to the Open Markets Institute, are concerned about the growing role of private equity in child care. A 2024 National Women’s Law Center report notes that center directors in private equity-owned companies report being “pressured to prioritize raising enrollment rates above all other considerations.”

Melissa Boteach, vice president of income security and child care at the law center, said the private equity footprint could expand further as more states pump public dollars into child care and preschool.

“We want those dollars invested in children and the teachers … not going to Wall Street,” she said.

Many states have bolstered public investment in the sector in recent years, including Colorado. Its $344 million universal preschool program, now in its second year, offers tuition-free half-day preschool to all 4-year-olds. It’s too soon to tell whether that will result in more private equity in Colorado child care, or whether more regulations might temper that.

Critics of private equity-controlled child care don’t think it should be expunged from the marketplace. Rather, they say that guardrails, including high state standards for quality, are needed. States, including New Jersey and Massachusetts have recently passed laws regulating large child care chains, many of which are backed by private equity.

“It’s much harder to roll back private equity’s deep entanglement in a sector than it is to prevent it in the first place,” said Boteach.

Big-name child care is backed by private equity in Colorado

The roughly 170 child care centers in Colorado owned or backed by private equity firms include big names such as KinderCare, The Goddard School, Primrose Schools, and The Learning Experience.

The Nest Schools, which will open a seventh Colorado location this summer, is one of the smaller national chains backed by private equity. Pastor said Rockbridge Growth Equity owns 33% of voting stock in the company. The company’s center in Aurora is currently on probation for a series of state violations, including leaving a child unattended in a classroom and allowing hazardous items to be accessible to children.

Chalkbeat identified one child care operator, Guidepost Montessori, that’s backed by venture capital investors, another investor type that Colorado’s proposed legislation would cover. Guidepost announced this month that all five of its Colorado centers will close in March “due to financial challenges.”

Typically, there are several minority investors in a venture capital round of funding, while private equity firms tend to take a majority stake in acquisitions, said Azani Creeks, senior research and campaign coordinator for the nonprofit watchdog group Private Equity Stakeholder Project. She said venture capital firms tend to invest in smaller companies, but have a similar profit motive to private equity firms.

Parent Brittney Bokoski, whose infant son and toddler daughter attended Guidepost’s Thornton center, said it was shocking to receive the closure announcement on Feb. 3, just a few days after balloons were put out to celebrate the center’s first anniversary.

One of the biggest problems at the center was staff turnover, said Bokowski, whose family pays about $4,000 a month for care at Guidepost.

Guidepost officials did not respond to Chalkbeat’s request for comment, but said in a letter provided to a local television station, “the labor market crisis of the past four years caught up to us in a big way in 2024

A few other for-profit chains with centers in Colorado were previously backed by private equity firms, but aren’t currently. They include Bright Horizons and Endeavor Schools, which together represent another 1% of the state’s child care capacity. Bright Horizons, which is now traded on the stock market, was previously owned by Bain Capital and Endeavor Schools was previously owned by Leeds Investment Partners.

Chalkbeat’s tally of Colorado child care centers owned or backed by private equity or venture capital firms is likely inexact. Sometimes, a center’s true owner is hidden by layers of parent companies. In addition, while the state recently started asking centers about their “governing body,” many responded with obscure acronyms, a person’s name, or the names of real estate or holding companies.

A spokesperson for Colorado Department of Early Childhood said the replies to that question can provide “limited information about oversight of child care programs” but recommended against using it to determine private equity ownership because the field isn’t required and was only added last August.

Mindy Goldstein owns a child care center in Lakewood called The Applewood School. When interest rates were lower, she said she’d get multiple calls a week from private equity firms interested in her center. Some representatives flew out to Colorado to meet with her.

She listened, but never bit.

“I don’t want to sell to private equity, but if I had to, it would be a really fast transaction,” said Goldstein, who estimated her center’s value at about $3 million. “They are the only ones who have money to buy it.”

She worries that a private equity buyer would lower her program’s quality, cutting back on the extra teachers she employs and the nutritious meals she offers. But she also pointed out that many working parents are desperate.

“I don’t think people care who owns it or who doesn’t own it,” she said. “They need care for their child and they’re on 10 waitlists.”

Colorado considers limits on private equity in child care

While the average parent may not know how corporate owners impact child care, some lawmakers are taking notice.

Garcia and two other Democratic state representatives have proposed new rules for child care companies or franchises that are owned or partly owned by private equity firms, venture capital firms, or other institutional investors. A bill introduced last month would bar such companies from getting state funding unless they agree to provide 60 days notice following the acquisition of a center before laying off staff or changing enrollment or eligibility rules for families.

These companies would also have to let child care centers maintain ownership of their property — a provision aimed at preventing “sale-leasebacks.” It’s a common practice in the private equity world that forces acquired companies to sell their property and then lease it back from the new owner. Experts say sale-leasebacks can harm companies financially by forcing them to shoulder a new expense.

Creeks, of the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, said it’s hard to determine which chains use sale-leasebacks. Companies have to report such transactions on tax filings, but nowhere publicly, she said.

Finally, the bill caps waitlist fees at $25 and requires child care tuition and fees to be publicly posted. (Similar provisions are in a separate bill that would apply to all licensed child care providers.)

Radha Mohan, who heads the Early Care & Education Consortium, a lobbying group for child care chains, said the bill could exacerbate the state’s child care supply crisis.

For example, she said, an investor-backed chain with only four centers — just below the five-center threshold in the bill — might ask, “Why grow my programs in the state of Colorado?”

Mohan said most child care providers are for-profit entities and that it’s deeply problematic to single out the slice of those providers backed by private equity and other institutional investors.

But Haspel, of Capita, said that’s like saying a corner bodega and a Kroger grocery store should be treated the same because they both sell groceries. The profit motive for child care chains backed by private equity or traded on the stock market is qualitatively different than for a mom-and-pop program, and should be regulated differently, he said.

Massachusetts reform law puts guardrails on child care chains

A few other states have also recently taken steps to curb outsized profit-seeking behavior in child care.

Last year, Massachusetts put guardrails on large for-profit child care chains — those with more than 10 sites in the state — as part of a child care reform law that earmarked nearly half a billion dollars in annual state grants for child care providers.

The rules require large chains receiving the grants to serve some lower-income children who receive state child care subsidies. They also require chains to use a certain portion of the grant for teacher pay and meet certain teacher wage minimums set by the state. Chains must also provide the state detailed financial information about how they use the grants. Finally, a single chain can receive no more than 1% of the state’s total grant program allocation, which was $475 million in 2024.

“The goal is not to make [large chains] go away,” said Elizabeth Leiwant, chief of policy and advocacy at Neighborhood Villages, an early childhood advocacy group in Massachusetts.

It’s to make sure teachers get paid fairly, classroom quality is prioritized, and children from lower-income families have equitable access to child care seats, she said.

Leiwant said Massachusetts lawmakers added the child care guardrails around the time Steward Health Care, a hospital group that had been owned by a private equity firm, collapsed financially last year, leading to hospital closures and mass layoffs.

“That just had a huge ripple effect throughout the state, both on communities and then also on the state government having to step in financially,” Liewant said. Lawmakers, she said, became “much more receptive to the idea that … if any industry is kind of allowed to go unchecked, that there can be issues down the road.”

Colorado’s private equity bill wouldn’t go as far as the law in Massachusetts. It doesn’t include requirements for teacher pay or limit the share of state money private equity backed child care centers can receive.

Problems at The Nest

Sara Flater’s 5- and 3-year-old were enrolled at The Nest Schools of Highlands Ranch location when the center was abruptly shut down on August 1.

Families were temporarily reassigned to other centers run by The Nest Schools, and Flater’s children ended up at different centers, one in Littleton and one in Centennial, she said. Flater expected classrooms would be set aside for children coming from the Highlands Ranch center, but that wasn’t the case. The kids were added to existing classes.

“It was very chaotic,” she said.

Flater expressed her frustration over the construction-related problems at the Highlands Ranch center in an email to Nest officials on August 15.

Five hours later, she heard back from The Nest’s co-CEO Jane Porterfield, who wrote that she deeply regretted that the center’s service had not lived up to Flater’s expectations. Porterfield said The Nest had “made many attempts to hear your concerns and thoroughly answer your questions.”

Porterfield went on to say, “Effectively immediately, we will no longer provide services to your family.”

Pastor did not answer emailed questions about why The Nest stopped serving the Flater family or about the company’s policies on such matters. Pastor said he and Porterfield, who are married, own a majority share of The Nest Schools and that Rockbridge Growth Equity has no operational control over The Nest except for C-level positions.

Flater said she didn’t know much about private equity when problems at The Nest began unfolding last summer. But after lots of Google searches, she started to understand how it works.

“I’ve come to the conclusion that private equity is just really bad for kids … It’s bad for families,” she said. “For us, it decimated our daycare, and it was just so sad.”

For a while, Flater cobbled together care for her youngest child after The Nest refused to continue serving her family. Her 5-year-old was in elementary school by that time. When she finally found a center that looked like a good fit for her son — a locally owned business — she had one big question: “Are you guys going to sell?”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org