Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

No one knows how many Colorado students are shut inside rooms, alone, at school.

But Riley Ellis-Beach knows that it happened to her son.

He was a small kindergartener, barely 30 pounds, with big emotions and a diagnosis of autism. When asked to do a task he didn’t want to do, he’d spit, growl, or cuss at school staff, according to a school behavior log. Sometimes he’d bite or hit. The staff began taking him to the “opportunity room,” where he’d stay for as little as five minutes or as long as an hour and a half, the log shows.

“Not until I had to go in and pick him up did we realize it was an empty room with nothing in it,” Ellis-Beach said. One time, she said she showed up to school to find her son in the room with the door shut. His special education teacher was peeking at him through a window, she said.

“He looked like a wild animal that had been trapped in a cage,” Ellis-Beach said.

State lawmakers have tried in recent years to better monitor and oversee seclusion, which means shutting a student inside a room, and restraint, which means physically restraining a student. But a loophole that legislators and advocates say was unintentional has meant that there is almost no public data about seclusion, while restraint data is more readily available.

Only 10 of Colorado’s 179 school districts included a separate tally of how many of their students were secluded last school year in the annual reviews that districts are required to file with the Colorado Department of Education, according to a Chalkbeat analysis of the reports. That’s despite a 2022 state law that was supposed to make data about seclusion available and “easily accessible.”

The lack of information makes it impossible to understand the scope of a controversial practice that some educators say is necessary to control dangerous student behavior but that many families say leaves their children with lasting trauma. Emily Harvey, co-legal director of Disability Law Colorado, called the use of seclusion “an unknown problem.”

“We have no idea how often it’s happening and who it’s happening to,” she said.

The data blackout also makes it hard for state lawmakers to know exactly what to do about seclusion. Two separate bills introduced last month in the state legislature aim to address the information gap. One of the bills goes even further and seeks to ban seclusion altogether.

“We know a seclusion room is an incarceration room,” said state Rep. Regina English, a Colorado Springs Democrat who is sponsoring the ban. “There is no way out for the student. There [are] locked windows and locked doors. That is, for me, inflicting intentional trauma.”

A change to solitary confinement law affects seclusion in schools

In 2017, Colorado lawmakers passed a bill that required school districts to complete annual reviews of their use of restraint and seclusion in an attempt to track it. School districts began complying in 2018, but a Chalkbeat investigation found that no state agency was collecting the annual reports. Essentially, the districts were policing themselves.

So in 2022, state lawmakers passed a bill that was supposed to make the data more transparent by requiring the Colorado Department of Education to collect the districts’ reviews.

But when the state education department went to write rules to put the 2022 bill into practice, it ran into what department spokesman Jeremy Meyer described in an email as “the complexity in our statutes regarding restraint and seclusion.”

Both the 2017 and 2022 bills required school districts to produce annual reviews of their use of restraint alone. That’s not because lawmakers didn’t want data on seclusion; they thought it would be included in the reports because Colorado law for years defined seclusion as a form of restraint.

What lawmakers working on the issue didn’t realize at the time was that in 2016, previous state lawmakers who were worried about restraint and seclusion in a different setting — youth jails — had created separate definitions of the two practices in Colorado law.

They did that so they could put more guardrails around the use of seclusion in youth jails, also known as solitary confinement, and collect more data about it. The 2016 bill followed concerning reports about the overuse of juvenile solitary confinement and the secrecy surrounding it.

That decision inadvertently led to the data collection problem that the education system is grappling with today, nine years later.

Because the state definition of restraint only refers to physical restraints and not seclusion, the disclosure rules developed by the Colorado Department of Education list just four data points that districts must include in their annual reviews: the number of physical restraints lasting more than one minute but less than five, the number of physical restraints lasting five minutes or more, and the number of students who experienced each. The rules say nothing about seclusion.

“It has created such a problem,” said Harvey of Disability Law Colorado. “A lot of people are asking, ‘How widespread is this problem?’ And I’m like, ‘Who knows?’”

Vast majority of Colorado school districts are silent on seclusion

Under the 2022 bill, the Colorado Department of Education began collecting annual reviews of school districts’ use of restraint in the summer of 2024.

Chalkbeat obtained all 179 reports through an open records request. While all the reports include data about the number of physical restraints performed on students, only 10 districts included separate information about seclusion: Cherry Creek, Aurora, Adams 12, Academy 20, Harrison, Cheyenne Mountain, Weld RE-1, Weld RE-4, Weld RE-5J, and Pikes Peak BOCES.

That means just 5% of Colorado districts reported seclusion data in their annual reviews.

Two of the 10 districts, Cheyenne Mountain and Weld RE-5J, reported zero seclusions in the 2023-24 school year. The data in the Weld RE-1 and Harrison 2 reports was redacted. The state allows the data to be suppressed if there are fewer than 16 incidents.

The other six districts reported a total of 907 instances of seclusion last school year.

The 2022 bill also required the state education department to “develop easily accessible, user-friendly profile reports for each school district” that would be posted on its website. The online reports were required to include a host of data ranging from chronic absenteeism rates to the number of students handcuffed to the number of students restrained or secluded.

The Colorado Department of Education did indeed launch the profile reports online. Meyer, the department spokesman, said the department collected restraint and seclusion data for the profile reports “but ultimately did not post it because we have concerns about its accuracy this year.” He pointed to “significant misunderstandings from districts in this first year of implementation.”

“We are working to ensure that districts are better trained on this data collection going forward so that we can present a more accurate picture in the future,” Meyer wrote in an email.

District says there’s a difference between seclusion and visits to the ‘opportunity room’

The Weld RE-4 district, where Ellis-Beach’s son attended, was one of the 10 that reported seclusion data for the 2023-24 school year. It reported a total of 39 instances of seclusion districtwide.

But the behavior log for Ellis-Beach’s son, a copy of which she provided to Chalkbeat, shows that the boy was sent to the opportunity room 63 times in the 2022-23 and 2023-24 school years. He was just one student in a district of 8,700. Chalkbeat is not naming him to protect his privacy.

Advocates and parents are concerned that school districts are under-reporting their use of seclusion by claiming that sending a student to a calm-down room is not seclusion. Seclusion is defined in state law as the placement of a person in a room alone “from which egress is prevented,” which means blocking them in. It’s only supposed to be used in emergency situations.

Even if school staff aren’t holding the door shut, advocates and parents have said, students are often told they can’t leave the room or feel that it’s forbidden.

Several entries in Ellis-Beach’s son’s behavior log say he was not let out of the opportunity room until he was sitting quietly. “OR - until sitting quietly against the wall with hands in lap,” one entry says. The duration? “100 minutes.”

In an emailed statement, Weld RE-4 Communications and Public Relations Director Katie Smith said there are “key distinctions between seclusion events and Opportunity Room visits.”

Weld RE-4 uses seclusion “in limited circumstances in which all other options are exhausted and if students pose a danger / threat to themselves or others for injury or probable injury,” she said.

Visits to the opportunity room, on the other hand, are “utilized for students of all abilities for a variety of purposes beyond seclusion and outside of disciplinary processes, including emotional regulation, privacy, and refocus space,” Smith said.

“This space provides a level of dignity and respect for our students,” she said.

“With the exception of use for seclusion, the student is actively engaged with a staff member the entire visit,” she said of visits to the opportunity room.

The monitoring requirements are different for seclusion, Smith said. A student in seclusion is continuously monitored by at least two staff members, and parents are immediately notified, she said. Legal documentation is completed that identifies the other options that staff tried, she said.

Neither parental notification nor legal documentation is required for visits to the opportunity room, Smith said, adding “however, our practice is to engage and communicate openly with our parents.”

Ellis-Beach said her son’s school didn’t give her a copy of the behavior log noting his visits to the opportunity room until she asked for it.

Seclusion has faced increased scrutiny

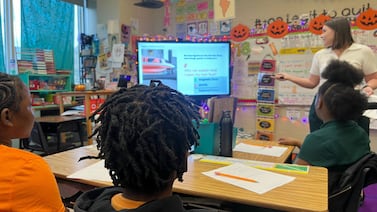

What little data there is shows that seclusion happens most often to elementary-aged children with disabilities that affect their ability to regulate their emotions. The practice has long been contentious, but it has faced increased scrutiny in Colorado in recent years.

In Douglas County, the U.S. Department of Justice opened an investigation into a case where a second grader was repeatedly secluded in the “blue room” and the “reset room” at his school. Federal investigators came to Colorado in January to interview witnesses, according to advocates and attorneys familiar with the case.

The status of the investigation is unclear. The U.S. Department of Justice did not respond to a question about the status of the case.

The Douglas County school board voted in January to ban seclusion rooms, but not seclusion. Douglas County School District Public Information Officer Paula Hans acknowledged the change in a statement, saying the board “recently updated district policies to eliminate the use of seclusion rooms. Additionally, the use of seclusion and restraint are limited to emergency situations only, when needed to ensure the safety of our students and staff.”

A case in which Denver middle school students were secluded against school district policy made headlines in 2023 and led to an internal investigation by Denver Public Schools.

That case sparked Rep. English to sponsor a bill to ban seclusion last year. But the bill faced pushback from educators who said seclusion was a necessary “last resort.” English ended up asking fellow lawmakers to postpone her bill indefinitely, effectively defeating it.

English is bringing the bill back this year. The new version, HB25-1178, would ban seclusion but also require school districts to publicly report their use of it “even though seclusion is prohibited,” the bill says.

“I’m absolutely trying to ensure there is proper reporting when it comes to seclusion,” English said of her bill. But she added that she hopes the reporting is unnecessary: “What I will say is we won’t even have to worry about this reporting because I’m out to ban seclusion wholeheartedly.”

Parents ‘sifting through the damages’ after son was secluded

A separate bill, HB25-1248, wouldn’t go as far. It would move the existing laws about restraint and seclusion in public schools from the section of Colorado law that deals with youth detention facilities to the section that deals with education — a move that one supporter characterized as “a common sense next step in standardizing restraint and seclusion.”

The bill also seeks to close the loophole that resulted in seclusion use being left out of most districts’ annual reviews by ensuring that it also gets reported to the state education department alongside restraint usage. HB25-1248 passed the House Education Committee last month on an 11-2 vote and now moves to the House Appropriations Committee.

Rep. Katie Stewart, a Durango Democrat who is co-sponsoring the bill, said at last month’s hearing that while the bill consists mostly of technical cleanup, “it puts us in a better place to understand the data and when restraint and seclusion are being used so we can do better for our students.”

Ellis-Beach and her husband Anthony Beach hope that’s true.

The couple describe their son as bright, resourceful, and curious. He loves the video game Minecraft and playing with Legos. He’s a “connections kid,” Beach said: He bonds easily with adults who he deems safe and who can help him calm the near-constant fight-or-flight response that his type of autism triggers.

The boy entered kindergarten at Windsor Charter Academy in the Weld RE-4 district in the 2022-23 school year. The behavior log notes that staff soon started taking him to the opportunity room. The incidents often began with noncompliance, the log shows: Staff asked the boy to complete a math worksheet or put away his book and he refused.

His parents said school staff often missed their son’s cues. If he chews on his pencil or picks at his eyelashes, it means he needs a break or a different approach to completing a task, they said. Instead, what often happened was a power struggle that ended with a trip to the opportunity room, they said.

In the opportunity room, the boy would climb the walls, strip off his clothes, and try to hurt himself, according to his parents and the behavior log. One entry says he picked his nose so deeply that it started to bleed. “When asked he said if he bleed [sic] enough he could go home,” says the log.

Windsor Charter Academy Director of Communications Sara Sanders said the charter school contracts with the Weld RE-4 school district for its special education services. Sanders said the charter school “will let the school district respond on our behalf.”

Weld RE-4 spokesperson Smith said the district could not discuss specific student cases.

Smith said Weld RE-4 works to ensure all special education staff are trained on non-violent crisis intervention each year, which “goes above and beyond the state’s training requirement of every two years.” Members of the district’s administrative teams and general education and transportation department staff also participate in annual training, Smith said.

Ellis-Beach and her husband eventually pulled their son out of Windsor Charter Academy in the fall of his first grade year after his arm got caught in a door, an incident recorded on a separate communication log. Ellis-Beach left her job as a teacher to homeschool their son.

But they said the damage had been done.

“Our son still brings up the opportunity room and being in seclusion,” more than a year after leaving the school, Anthony Beach said. “We’re still kind of sifting through the damages to our son and trying to get him back on a path of wanting to learn again.”

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.