Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

The number of students in Colorado public schools is declining. But enrollment in Colorado’s publicly funded, privately run charter schools is heading in the opposite direction.

Charter schools enroll approximately 136,220 students this year, up nearly 13% from 120,740 students in 2017, according to numbers from the Colorado Department of Education. In that same period, district-run schools had a 5.6% decline in enrollment. And altogether, the state’s total public school enrollment shrank 3%. The number of charter schools is up too, from 250 schools in 2017 to 262 this year.

The vast majority of Colorado’s approximately 880,000 public school students — 85% — still attend public schools run by school districts. But the trend of rising charter school enrollment, even as total enrollment drops, shows that more families are interested in and ultimately choosing charter schools, which sometimes have unique models or programming.

As charter school enrollment increases nationwide, tensions can rise between district-run schools and their teachers unions on one side, and charter schools and their parents on the other over student enrollment and the funding that comes with it. Critics have wondered if allowing new charter schools, especially in communities with declining overall enrollment, could lead more district-run schools to shrink dramatically or close.

In some cases, school districts are feeling the pressure to diversify their own options, reimagining schools, or creating new magnet schools, or themed programming, though often with fewer resources to do so.

Colorado was one of the first states to pass a law allowing charter schools. School choice, or the ability for students to apply to attend any public school in the state, has also been protected by state law for decades. And while a ballot measure that would have enshrined a child’s right to school choice in the state constitution failed in November, its supporters may bring it back.

Charter school fans say families are looking for more choices and different models of learning that can keep children engaged. In some cases, families are following programming that has been cut from district-run schools.

People want “more options out of public education. It’s a fact that was exacerbated by the pandemic,” said Dan Schaller, president of the Colorado League of Charter Schools. “That is ultimately what charter schools represent.”

But to critics, charter school growth represents a threat to district-run schools. That threat is especially big because charter schools can raise money from wealthy donors to help market their schools and recruit students, opponents say.

“I just think there’s a false narrative that our public schools are failing,” said Judy Solano, chair of Advocates for Public Education Policy, a Colorado advocacy group. “But it’s a matter of unequal resources and marketing. Many of our larger chain charters are funded by very large wealthy families.”

State lawmakers are considering a bill that would add new financial reporting requirements about district-run and charter schools’ private funding, money they spend on marketing, and their teacher salaries.

Some have also criticized charter schools for not always serving populations of higher needs students such as students with disabilities like district-run public schools do. A state rule change in 2022 makes it more clear that charter schools can’t ask about disabilities in enrollment applications.

But as more students enroll in Colorado charter schools, their student demographics are moving closer to matching those of district-run schools, data shows.

Charter schools now serve the same percentage of English learners as district-run schools. In addition, more than 50% of students in both types of schools identify as students of color. Charter schools reached that percentage last year, while district-run schools reached it this year.

But district-operated schools are still more likely to enroll students with disabilities than charters. And charters remain less likely to enroll children from low-income families, although that gap is closing.

Some charter schools cater to unique interests

There are many reasons why a new charter school might open and why students might choose it. Sometimes, as in Park County, it’s a matter of variety and geography.

The South Park County Re-2 school district only has one elementary school and one that combines middle and high school grades. There are also two charter schools. But for people in some parts of the district, such as Fairplay, those choices are about an hour’s drive away.

It was top of mind when Laurel Dumas left her job as principal of a district-run school and decided to create a new micro charter school focused on outdoor learning. High Rockies Community School will open next fall.

“A lot of people live here to be outdoors and enjoy skiing and doing outdoor activities, and people wanted the same for their kids,” Dumas said.

The High Rockies program calls for multi-age classrooms, students collaborating on projects, and learning from the community. Each day will start with outdoor activities.

“It looks like recess at first, but then you see the kids are playing whatever they’re learning,” Dumas said. “If they’re learning about the beaver ecosystem, suddenly there’s 15 beavers running around.”

The school is currently testing out some of its programming through a homeschool enrichment program. High Rockies already has 31 students enrolled for next year and has started a waitlist.

Dumas said that the school’s unique model is attracting teachers to the area. Schaller, in turn, also pointed to other charter school models in Colorado that focus on topics like aerospace and agriculture.

“In my experience being a principal in a rural area, we were lucky if we got enough applicants for the positions we had,” Dumas said. But now, she said, “we’re able to find people who fit the model” because “we’re working on something we really believe in.”

High Rockies Community School was not authorized by the South Park County school district like the other two existing charters in the area, but by a state agency called the Charter School Institute, or CSI. While most charter schools are authorized by the school district in which they’re located, CSI can authorize charters when districts are unsure how to support a charter, or uninterested in doing so.

Dumas said she wanted the support of CSI, which has more experience to support her small school.

CSI has also expanded and now authorizes more schools. Its 46 charter schools enrolled more than 21,000 students this year, an increase of over 20% from 2017.

Some worry charters can lead to school closures

As charter enrollment rises and total student population falls, school districts that authorize charter schools can face especially tough decisions.

Of Colorado districts that authorized charter schools in both 2017 and 2024, 76% saw enrollment decrease in their district-run schools in that time period. Only 63% of districts that don’t authorize charters saw enrollment decrease.

Some parents and district officials have questioned whether it’s wise to authorize new charter schools when enrollment is declining.

School board members in Jeffco Public Schools lamented in 2016 that they were not able to reject the application for a new charter school, Great Work Montessori, due to concerns that the school would not enroll enough students to be financially viable.

Great Work Montessori opened in 2017. But it closed in 2023 due to low enrollment and the district’s concerns about its performance.

Months earlier, the board had voted to close 16 district-run schools for low enrollment, including a couple just miles from the charter school.

Charter school enrollment in Jeffco has declined since 2017, but not as much as enrollment in district-run schools. In the 2017-18 school year, Jeffco charter schools enrolled 9,763 students. That enrollment is down to 9,236 in the current school year.

In the same period, enrollment in district-run schools has declined more than 13%, down to 66,259. Last year, the district closed another school but worked with a charter school to have it take over serving the community.

Denver Public Schools is also closing district-run schools for low enrollment. Charter schools in Denver have been affected by declining student counts, too.

Earlier this year, Denver’s GALS all-girls charter school — which focuses on physical education — announced it would close its high school grades, after enrollment in them fell to just 58 students.

At least 14 other Denver charter schools have closed in the past seven years, most because of declining enrollment. Without “sufficient demand,” said Schaller of the Colorado League of Charter Schools, “the finances are not going to be there either.”

In Douglas County, enrollment is growing in some parts of the district but falling in others. That has sparked debate about how to serve students in the parts of the district that are growing.

As in other districts, the number of Douglas County families choosing charters is rising. Enrollment in Douglas County charter schools is 16,445 students, about 1,200 students more than in 2017. Over the same period, overall enrollment in district-run schools has fallen by about 6,900 students to 45,406.

Now, there’s concern that the growing Sterling Ranch neighborhood won’t be able to support both a charter and a district-run school. A new district-run school is expected to open in that area in the fall of 2027. But some residents are concerned that the John Adams Academy charter school may open there first.

Douglas County parent Suzanne Collins said she’s not against charter schools. Her daughter actually attends one, because it was where Collins could find full day preschool in 2019. But she worries that the projections for the number of students in Sterling Ranch, where she lives, won’t be enough to allow the two schools to be sustainable.

“I believe charter schools and neighborhood schools can both thrive when they’re part of a thoughtful, coordinated district plan that ensures high-quality education for all students,” Collins said. “In this case, I’m concerned that the JAA proposal could undermine our long-awaited neighborhood school before it even opens.”

Charters, district schools can coexist well, some say

Not all parents or school districts see charter schools as adversaries.

Aurora Public Schools Superintendent Michael Giles said that charter schools are part of the district’s “portfolio of learning opportunities.”

Total enrollment in Aurora Public Schools has been going up since the 2021-22 school year and the number of students is close to what it was pre-pandemic. But even before that, when the district was losing students, charter schools were expanding in the area.

While charter school growth wasn’t enough to offset overall district enrollment declines, Giles said that from his district’s standpoint, “it’s always great when we can keep our kids in our community.”

In the fall of 2017, Aurora charter schools served 5,073 students. That figure rose to 6,530 students in the fall of 2023, before declining for the first time in eight years because a charter school closed.

As charter schools grew in Aurora, the district decided to diversify its own options.

The strategic facilities plan the district voted on in 2019 called for expanding thematic magnet programs to provide in-house school choices. That part of the plan came in response to communities asking for more choice.

One of the envisioned schools is opening next fall, a health and sciences high school near the Anschutz medical campus. It will be the district’s sixth magnet school. The district is working on a new facilities plan, but it’s unclear how it will handle magnets.

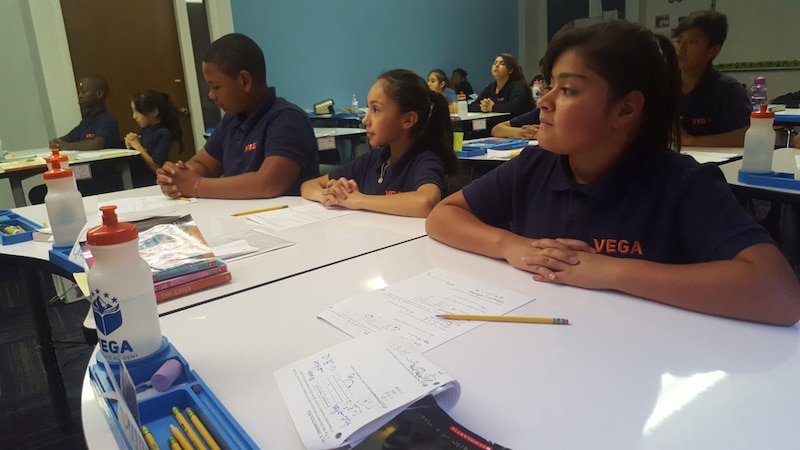

Vega Collegiate Academy is one of the Aurora charter schools that has grown rapidly. The school this year serves 583 students, up from 310 in the fall of 2020 and 96 in 2017, its first year.

Executive Director Kate Mullins said that growth stems from her staff’s work during the COVID shutdowns, when they made weekly deliveries to families and were able to retain most students.

Then two years ago, when there was concern that enrollment was going to decline, she spent $50,000 paying staff to go out canvassing. Staff, along with some volunteers, ended up recruiting 140 students from the neighborhood that summer.

Many of the families they encountered were new immigrants who responded to Vega’s free busing to the school, free school supplies, before- and after-school care, a four-day school week with optional Saturday school, and shorter summer breaks.

“For our families, that provides a lot of consistency,” Mullins said.

The school didn’t have to spend much of its $50,000 marketing budget last year, because many of those migrant families spread the word to other newly arriving families, she said.

“The kids are there,” Mullins said. “They just have to believe you’re the right place for them.”

Yesenia Robles is a reporter for Chalkbeat Colorado covering K-12 school districts and multilingual education. Contact Yesenia at yrobles@chalkbeat.org.

Kae Petrin is a data & graphics reporter who covers data related to K-12 education, voting rights, and public health for Civic News Company. Contact them at kpetrin@chalkbeat.org.