Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Two of Colorado’s largest school districts will start universal dyslexia screening programs next school year, joining about a dozen other districts across the state that already look for signs of the learning disability in young students.

The Jeffco and Douglas County districts, which together serve 137,000 students or about 15% of the state’s students, are the latest to announce plans to screen all students in certain grades for dyslexia. It’s a move that could soon be mandatory for Colorado’s 178 districts if a bill now in the legislature becomes law. Senate bill 25-200 would require universal dyslexia screening in kindergarten through third grade starting in the 2026-27 school year.

The two districts’ screening plans, along with the possibility of a statewide screening law, represent a sea change from five years ago. In 2020, no Colorado districts screened all students in early grades for dyslexia, a common learning disability that makes it hard to identify speech sounds, decode words, and spell them. In addition, the first push for a statewide dyslexia screening law had fizzled the year before, leaving only a small state pilot screening program as the consolation prize.

But parents of children with dyslexia and some educators continued to advocate for change, and slowly the tide turned.

Boulder Valley, which has 28,000 students, was the first sizable Colorado district to launch universal dyslexia screening, starting with all kindergartners in the 2022-23 school year. Next year, district officials say they’ll also screen any students in first through third grade who haven’t already been screened.

Screening is meant to detect signs of dyslexia, but doesn’t definitively diagnose it. About 15% to 20% of the population has dyslexia, according to the Colorado Department of Education. With the right instruction, students with dyslexia can do as well as their peers in school.

The Trump administration’s goal of dismantling the U.S. Department of Education raises questions about how services for students with disabilities would be funded and overseen.

The Jeffco school district, Colorado’s second largest, will launch its screening program next school year for students in kindergarten through third grade. The Douglas County district will start screening kindergartners in the spring of 2026 and first graders in the fall of 2026.

Valerie Thompson, a school board member in Douglas County and the mother of a third grader with dyslexia, said getting dyslexia screening in place has been a huge priority for her.

“We know that early intervention is most effective,” she said. “When you get to third and fourth grade, the timeline and the amount of resources needed are a lot larger.”

They knew something was wrong

Jennifer Forsha, a Jefferson County mother, knows what it’s like when years go by without the right kind of reading help

When her son Kaden was in kindergarten in the Jeffco district, she saw his reading struggles. His teacher did too, but the extra help the school offered didn’t seem to make much difference. Forsha got Kaden a tutor, but that didn’t help either.

Finally, just before second grade, Forsha paid $1,400 to have Kaden tested by an outside specialist for dyslexia. It confirmed her suspicion, but there was still a long road ahead. By the time he started second grade, he’d fallen to the third percentile for reading and his confidence was shot.

With the help of specialized tutoring, a special education plan, and dyslexia camps, Kaden, who is now a 10th grader, gradually regained his lost ground, eventually moving to the 55th percentile in reading.

Looking back, Forsha said she wished she’d had him evaluated for dyslexia in kindergarten.

“We could have caught this earlier,” she said.

Thompson knows the feeling.

From her son’s first day of third grade last fall, she saw his anxiety growing, especially because of the increasing emphasis on writing. He began dreading school, having near daily breakdowns. Thompson or a counselor would walk him to the classroom each morning because otherwise he would linger in the hallways, overcome with nerves.

Then on back-to-school night, Thompson and her husband saw a display of student writing samples on the wall. Her son’s was starkly different from the others — far fewer words, poor handwriting, and rife with wild misspellings.

They knew something was wrong and quickly set up outside testing. It revealed that the third grader had both dyslexia and dysgraphia, a learning disability that makes writing difficult.

Thompson’s son now gets more tailored support at school, plus speech therapy and twice-a-week literacy tutoring at home. Things are slowly improving after a stressful and emotional year, Thompson said.

Recently, at a parent-teacher conference, the third grader was proud to show off a story he’d written about a snowman.

“He was very excited to show me the amount of words he managed to get on a piece of paper,” Thompson said.

Momentum for screening builds alongside other reforms

The yearslong push for dyslexia screening in Colorado schools has developed alongside a series of state efforts to improve reading instruction by mandating better curriculum and teacher training.

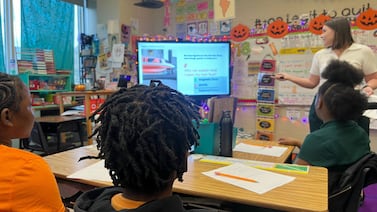

Over the past five years, many districts, including Jeffco and Douglas County, have adopted new elementary reading curriculum that more closely aligns to the “science of reading,” a large body of knowledge about how children learn to read.

In 2021, Jeffco also launched a unique program for middle and high school students with dyslexia that includes intensive daily reading instruction plus other supports. After a short-lived plan to scale back the program last spring, district officials pledged to save it.

While Colorado’s third graders finally exceeded pre-pandemic proficiency rates on the state literacy test in 2024, the rate is still relatively low at 42%.

Officials in the Douglas County district said some of their 48 elementary schools are already screening young students for dyslexia, but next year it will happen more consistently districtwide. They said they’ve consulted with the Boulder Valley district as they’ve planned the effort.

As for whether the new initiative will identify more children with signs of dyslexia, district leaders say it’s an open question.

“It’s possible,” said Deputy Superintendent Danelle Hiatt. “We just recognize how important it is to identify our students as early as possible if they are showing characteristics of dyslexia or reading challenges.”

Ann Schimke is a senior reporter at Chalkbeat, covering early childhood issues and early literacy. Contact Ann at aschimke@chalkbeat.org