For thousands of Detroit families, the daily trek begins in darkness, before dawn.

Myesha Williams, a mother of eight on Detroit’s west side, sets out at 7 a.m. to deliver her three school-aged sons to three different schools on opposite ends of the city – and she considers herself lucky. She has a car and a large family that can help share the driving.

Total daily journey: Up to 93.5 miles, 3 hours.

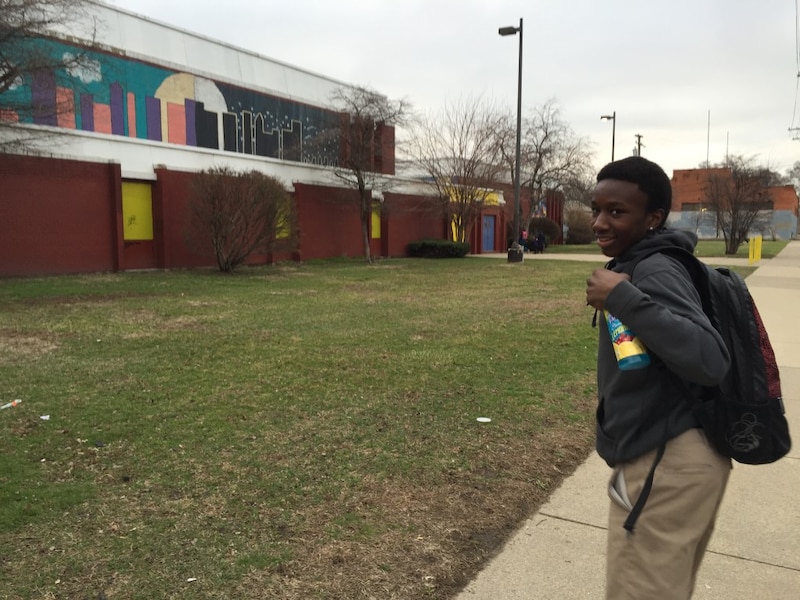

Monique Johnson starts her trek even earlier, just after 6 a.m. when she and son Shownn, 13, an eighth-grader, catch a ride to a bus stop eight blocks from their home in the city’s Brightmoor neighborhood. There are closer stops, Johnson said, but they’re pitch black at that hour — and dangerous.

They wait for the bus in the glow of a nearby gas station, huddling together under blankets on frigid winter mornings. The No. 43 bus comes around 6:20 a.m., Johnson said.

Shownn is exhausted at that hour and sometimes sleeps on his mother’s shoulder during the 25- to 40-minute ride along Schoolcraft Road toward Woodward Avenue. The bus drops the pair at the corner of Woodward and Manchester in Highland Park. Mother and son typically wait 20 minutes for their next bus, the No. 53, while peering warily through the dim light cast by the Walgreens across the street.

“It’s pretty dark on that side of the street,” Johnson said. Shownn knows to stay alert. “I teach him to pay attention to his surroundings so he’ll be able to react if he feels something is not right.”

Mother and son typically arrive at University Prep Science & Math Middle School, a well regarded charter school in the Michigan Science Center, around 7:30 a.m. and Johnson waits with her son until his classes begin at 7:50. She then makes her way back home — another No. 53, another No. 43 – until reaching Brightmoor around 9:30 a.m. That’s about three and a half hours before she has to leave again on another four buses to return to Shownn’s school and bring him home.

Total daily journey: 52 miles, 5-6 hours.

Like many big cities, Detroit has shuttered scores of traditional neighborhood schools in favor of charter schools and public school magnet programs. Detroit kids can also attend schools in suburban districts.

"If he’s passionate about it, then I’m going to do whatever it takes in rain, sleet, snow, bus and bike"

But many of the city’s new options do not provide transportation, and new schools are often far from where kids live – a serious challenge in a city where a quarter of families have no access to a car and where the public transit system is woefully insufficient.

That means some families, like Williams’ and Johnson’s, make extreme sacrifices to access quality schools. Work gets neglected; personal obligations go unmet; children miss sleep and lose ground in class by too often showing up late.

Other families, those without cars or the time and resources to make long commutes to school, are stuck with the few schools left in their neighborhoods. And the nearby option is often a school with a long track record of poor performance: Just 10 Detroit schools posted test scores high enough to rank above average on the state’s last top-to bottom ranking in 2014 — six selective public schools and four charter schools.

And with the families who can leave choosing to do so, many local schools have lost the engaged parents who once led the PTA. They’ve lost connections to community leaders who are less likely to advocate for a school their children do not attend. And their neighborhoods have lost the community anchors that once brought them together.

“One of the outcomes of schools closing and kids having to go farther and farther away from home is it’s much more difficult for the school to create bonds with families that would serve to support school improvements,” said Sarah Lenhoff, an education professor at Wayne State University. “The neighborhood around the school may not feel as strong a connection to it if none of their children are going to that school.”

School choice

The schools that once gathered the families of Johnson’s neighborhood, Brightmoor, are largely gone now – Vetal, Burt, Harding, Hubert, Houghten, Redford High.

It’s the same in Williams’ neighborhood on the city’s near west side. Robeson burned down. Hancock was shuttered. Longfellow became Detroit City High School, then closed its doors.

They were among 195 Detroit public schools that closed between 2000 and 2015 as the district’s enrollment fell from 162,693 students to 47,959. More than 100 new public and charter schools opened during the same time period, but the new schools weren’t placed around the city based on neighborhood need.

Any college or university in Michigan can authorize a charter school and charter schools can open anywhere they find an appropriate building. So schools open where real estate is available, there is a perception of safety, and teachers want to work.

The result is a mismatch between where students live and where schools are located.

A calculation by Data Driven Detroit and the advocacy group Excellent Schools Detroit shows that Detroit’s affluent downtown and midtown neighborhoods have 17,039 more school seats than children who need them.

The struggling neighborhoods in northeast Detroit, in contrast, have 2,130 more children than seats.

Williams’ neighborhood, around the center of the city, has 1,694 more children than seats.

The prominent city leaders behind the Coalition for the Future of Detroit Schoolchildren last year flagged this imbalance in a report that issued a series of recommendations for turning around the city’s schools.

"It would be a blessing if you could get a quality education in your own community where you don’t have to get up extra early and travel."

The coalition called for the creation of a Detroit Education Commission that would have oversight authority over public and charter schools to better distribute school options around the city. The idea is now the subject of heated debate in Lansing where the Senate version of a $715 million rescue and reform plan for Detroit Public Schools would create the education commission. The idea is opposed by charter school leaders who fear the commission would favor public schools over charters and are lobbying to keep the DEC out of the final legislation.

Even if the DEC is created, however, it would primarily have control over future schools — not current ones — so it would likely take years for it to have an impact on neighborhoods that need quality schools.

In Johnson’s Brightmoor neighborhood, there are technically enough school seats, but none of the nearby options meet Johnson’s standards for Shownn, she said.

Of the five public and charter schools in Brightmoor that were listed on the state’s most recent top-to-bottom rankings in 2014, four had test scores that placed them in the bottom 6 percent of Michigan schools. The only Brightmoor school not at the very bottom was a charter high school that Shownn is still too young to attend.

So when Shownn came home from a field trip to the Science Center and told Johnson there was a school he wanted to go to inside the center, she agreed to bring him there on the bus every day. His charter school was ranked in the 59th percentile on the state ranking.

The schedule has taken a toll on Johnson and her family, she said. With so much of her day devoted to transporting Shownn to and from school, it took her years longer than it should have to graduate with a journalism degree last year from the University of Michigan-Dearborn. Now, as she looks for work that will pay enough to buy her a car, the schedule interferes with her job search, too.

But this was the best way to help Shownn achieve his goal of going to college, Johnson said. “I have to do this to make his dreams happen. If he’s passionate about it, then I’m going to do whatever it takes in rain, sleet, snow, bus and bike. I’m going to make it happen.”

Williams said she initially sent her son Elijah, now a 17-year-old sophomore, to the nearby high school, Central Collegiate Academy. It’s close enough that Elijah could walk home. But he struggled there.

“I was getting in trouble,” Elijah said. “The environment at Central is not good.”

So when his basketball coach at Central got a job at the Cornerstone Health and Technology charter school in northwest Detroit, Elijah followed him.

Williams initially enrolled 14-year-old Edmond at the Phoenix Multicultural Academy in Southwest Detroit because she worked there and could bring him with her when she went to work. She enrolled another son in Southwest Detroit’s WAY Academy because it was close to Phoenix and would let 15-year-old Emmanuel, who has fallen behind academically, quickly make up his lost credits by taking online classes.

But when she lost her job at Phoenix, which has been struggling and might close this year, the drive to Southwest Detroit became much more of a challenge. Now, if her husband can’t take Elijah to Cornerstone in northwest Detroit, she makes a half-hour trip to drop Elijah at that school and then comes back for Edmond. It takes 50 minutes to make the round-trip drive to drop Edmond at Phoenix, then another 50 minutes a few hours later to take Emmanuel to his school, which starts at noon.

Williams’ daughter-in-law and other family members often help with the driving, but someone in the family has to drive back to Southwest Detroit in the afternoon to pick up Emmanuel at 3 p.m., then sit in the car for over an hour, waiting for Edmond to get out of school at 4:15 p.m.

“It would be a blessing if you could get a quality education in your own community where you don’t have to get up extra early and travel,” Williams said. “But I’ve been blessed with my car … I just really thank God for me and my husband because we just had to go above and beyond for the kids.”

“A sin and a shame”

Dawn Wilson, Johnson’s neighbor in Brightmoor, knows what it’s like to go to a nearby school. Her daughters attended a small pay-what-you-can religious school around the corner from her home when they were younger.

“I loved it. It was like family,” said Wilson, a professional clown who once performed at many of her neighborhood’s schools. “We would walk there and the teachers lived in the neighborhood. There were a lot of community events and everyone would come.”

The closure of that school kicked off a decade of bouncing her five children around to a motley mix of public, charter, and parochial schools that, one by one, disappointed Wilson and her kids. One school was too violent, Wilson said. Another had five principals in four years. One charter school changed management companies in the middle of the school year.

Every year, she drives a different route, taking kids to different schools, while watching as schools in her own neighborhood have emptied out and become vacant and derelict.

“Look at this! This is a sin and shame,” Wilson said as she gave a reporter a tour of her neighborhood’s abandoned schools.

Hubert has been open to trespassers and scrappers. At Houghten, which the city began to demolish this week, a roof collapse makes the building look like it has been bombed.

“If you ever want to break a community, just start by breaking down the school system and eventually you’re just going to have deserts and graveyards,” said Arlyssa Heard, the policy director 482Forward, a parent advocacy organization.

“If you have a good school in a community, people will start moving into that community and goods and services flow to where the people are,” Heard said. “When you have kids in a neighborhood, people are more apt to have a neighborhood watch. Police respond better. People can fight for playgrounds and safe spaces … But when you eliminate schools, tear them down, rip them out of neighborhoods and shut them down without even consulting the neighborhood, then you end up with these [school] deserts and you have parents who can’t afford to move or uproot their families. You have them driving all over town trying to take five kids to five different places. It’s completely insane.”

That has left the institutions that serve the neighborhood’s children scrambling to hunt them down.

Cherie Bandrowski has operated a tutoring and mentoring program for kids in Brightmoor since 1986.

The Wellspring youth development center she runs with her husband Dan is across the street from the broken and vandalized building that used to be Houghten school.

“Kids would come across the street to our program,” Bandrowski said. “The elementary school kids came from there, the high school kids came from Redford High … Now they’re all over the place — charter schools, open districts, DPS.”

Instead of serving kids from the neighborhood, Wellspring now sends a bus to pick up students from Cody High School, six miles away. Other students get a ride from their parents — at least on days when the family car is in working order.

“It’s not community,” Bandrowski said. “Back in the day, we would know the whole family and we knew that so-and-so’s parents were crack users … Today, we still know the families but there isn’t quite that intimacy anymore.”

A new path

Detroit schools have intensive needs. The city’s students have some of the lowest test scores in the nation and the district has a long-term debt that, by some estimates, tops $3.5 billion. Both the House and Senate in Lansing seem poised to pass some kind of rescue plan to at least address DPS debt.

Whether the Detroit Education Commission is included in the legislation will be determined over the next few weeks as lawmakers return from spring recess and resume negotiations. The DPS legislation passed by the Senate last month would give the city’s mayor the power to appoint the seven members of the DEC. They would be charged with creating an annual school needs assessment based on community input and data. The DEC would then have the power to steer new schools to neighborhoods that need them most.

“It’s not going to fix everything,” said Heard, who was a member of the coalition that recommended the DEC. “But the DEC will be able to at least bring some level of sanity to what we have now. What we have now is completely unacceptable.”

Charter school supporters don’t dispute that the current situation is difficult for many families, but they say giving the mayor power over charter schools would stifle school choice. They have instead advocated for a system of incentives to lure charter schools to the neighborhoods that most need new schools.

“There are things that can be done to make parent access to choice easier, and those things should be done,” said Gary Naeyaert, executive director of the pro-charter Great Lakes Education Project. “We just want them all to be opt-in and voluntary” for schools.

It’s true that many charter schools have clustered in neighborhoods like downtown and midtown, he said, but he asserted that those schools are popular with parents who work in the city center and drop off their children on the way to their jobs.

“It is also commonly believed that that area of the city is a safer area in which to locate a school than some other areas of the city,” Naeyaert said. “It doesn’t do anyone any good to put a school where it can’t get enrollment.”

School choice options are so popular with parents that less than 40 percent of the city’s 119,000 school-aged children are enrolled in the Detroit Public Schools. The average Detroit student commutes 3.4 miles each way to school but for some parents, the journey is much longer.

“Everything I do is to make things better for him,” Johnson said of her son. “I told him ‘We’re going through these extra steps and it’s a lot to get you to school, but if this is going to help better prepare you, not only for high school and for college, but for life, then it’s what we’re going to do.’”

Next year, for high school, Johnson has a highly ranked charter school in Dearborn in mind for Shownn. It’s a 15-minute car ride but about an hour away on the bus.

“My plan is that I’ll have a car before he gets to high school,” Johnson said. “But even if I don’t, we’ll catch the bus if we have to. He did it for three years in middle school. He’s a trooper.”