At a time when cities across the country have long waiting lists for every seat in free, quality preschool programs, Detroit has a different problem: hundreds of unused seats.

Of the 4,895 seats that the federal government funds for Head Start programs in Detroit, nearly 800 are empty because providers have struggled to fill and open classrooms.

That means that in a city where 94,000 children live in poverty and where the need for licensed childcare reportedly exceeds availability by more than 23,000 kids, many children who could benefit from early education aren’t getting it.

The problems preventing Head Start providers from putting kids in classrooms are years in the making.

The program, which is emerging from a wrenching upheaval, suffered years of deterioration and neglect that have made it difficult to find and retain qualified teachers and to locate classroom space that can realistically be brought up to code.

“The depths of poverty and the depths of long-term disinvestment that’s happened in Detroit for decades, you can’t really match that in Houston or Miami or some of the other cities where Head Start operates,” said Katherine Brady-Medley, the Head Start program director at Starfish Family Services, one of four agencies that run Head Start in Detroit.

But while Detroit’s problems are more severe than elsewhere, the city also has an unusual solution: a remarkable collaboration among local philanthropies to expand early childhood programs that has boosted the number of children enrolled by 20 percent in just the last year.

The unconventional effort is drawing attention from early childhood advocates across the country. But to make an even bigger difference, it will need to address serious facilities and staffing challenges — problems that have proven difficult to solve.

* * *

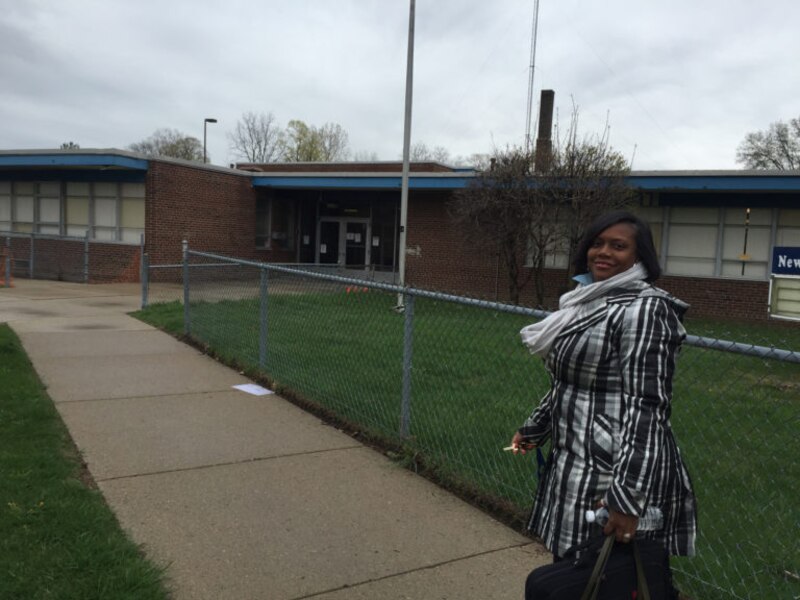

The issues facing the city’s early childhood programs are on stark display at the Winston Development Centers Head Start on the city’s northwest side.

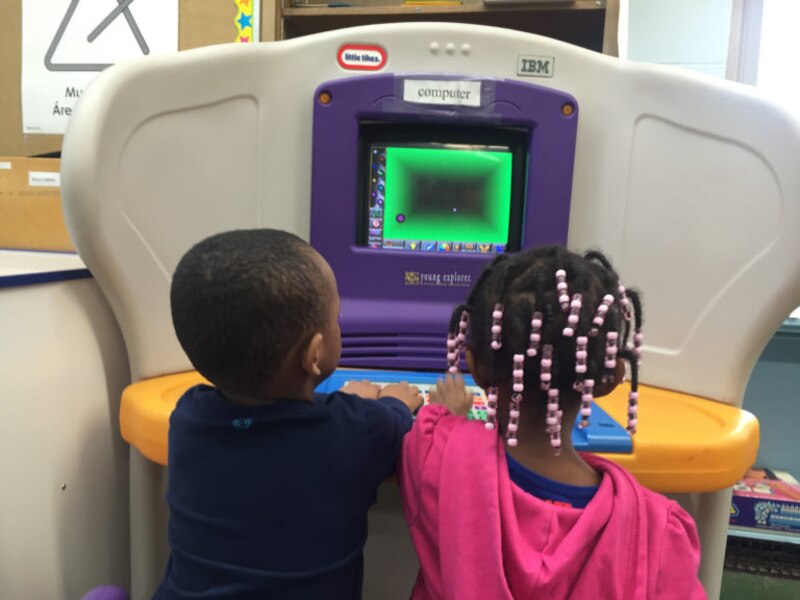

Winston offers bright, colorful classrooms, engaging activities and nutritious meals to low-income kids that will give them a leg up when they get to kindergarten. Studies on Head Start show the federally funded program can influence everything from whether kids succeed in school, to whether they become smokers as adults.

But the school is in such poor repair that on frigid winter mornings, some families get calls telling them to keep their children home. A broken boiler leaves some classrooms too cold to open.

"Of the 4,895 seats that the federal government funds for Head Start programs in Detroit, nearly 800 are empty because providers have struggled to fill and open classrooms."

“If you have to go to work, it’s an issue,” said LaKeyia Payne, whose 5-year-old son Carlos has attended Winston since he was three. “People’s jobs are not that flexible and they may not have family support, so for some, it’s very irritating.”

The school also has classrooms that have seen a rotating cast of teachers. Low pay and the stress of working with children with intensive needs has meant that too many teachers have left too soon – and been too hard to replace.

“In this classroom, just [this year], there have been two other teachers before me,” said Trenda Jones, an assistant teacher who started at the school in February in a classroom that is currently without a permanent lead teacher.

Winston’s challenges are hardly unusual. Early childhood teachers’ pay is typically low and stress is high. In fact, Winston is better off than some schools, since it has substitutes on staff who can fill in when teachers leave. Other schools don’t have enough teachers for all of the classes they have federal funds to offer.

Other schools also have not been able to open all of the classrooms they need since many of the schools and churches that have housed Detroit Head Start programs have deteriorated so severely during years of financial struggle that providers have difficulty bringing them up to code.

These issues, combined with the challenge of spreading the word to parents about available openings, are why the federal Administration for Children and Families says that just 84 percent of Detroit’s funded Head Start seats were filled last month. That’s compared to the national average where more than 95 percent of funded Head Start seats were filled.

But Head Start in Detroit is a system in transition.

The city had managed Head Start programs since their creation in the 1960s until four years ago, when the Obama administration responded to years of mismanagement by inviting nonprofits and other agencies to bid on contracts to run the program.

Many of the family service agencies that ultimately won the contracts in 2014 had been running small-scale Head Start classrooms in churches or schools under the city’s contract. Now they would have to expand quickly to meet new obligations.

The new contracts directed more money to programs for younger children – not just the 3- and 4-year olds who have traditionally been served by Head Start, but also babies and even pregnant women.

That meant scores of new classrooms had to be renovated and hundreds of teachers needed to be swiftly hired.

“That was more difficult than a lot of them realized,” said Kaitlin Ferrick, the director of Michigan’s Head Start Collaboration office. “They were having hiring fairs where they were trying to hire a couple hundred teachers and really having a challenging time. It’s been a struggle.”

The changes to Head Start were happening as Michigan ramped up spending on pre-kindergarten programs – one of the largest preschool expansions in the country.

That opened early childhood education to more children. But it also introduced competition between state-funded pre-K programs and federally funded Head Start for teachers, exacerbating already high turnover and creating turmoil for kids.

“Anytime you lose consistency in the classroom, the classroom can kind of turn,” said Rhonda Mallory-Burns, the Development Centers director who oversees Winston and four other centers. “It can impact the development of the children.”

Development Centers has a robust program to try to keep teachers in their jobs. It does extensive professional development and has twice-annual “wellness days” where teachers can get massages, pep talks and even Zumba classes from devoted volunteers.

“We get back massages. We get smoothies. We just get a lot of pampering on that day,” said Margaret Jones, 65, who works at the Development Centers site on West Seven Mile Road.

But early childhood salaries are notoriously low — Development Centers pay $19,956 for an inexperienced assistant teacher to $42,998 for an experienced master teacher — and the work the teachers do is demanding.

“Some of the kids can be overwhelming, especially when you don’t get help from the parents,” said Jones, who said she retired last year due to “burnout” but came back this year because she needed a job. “We get kids with behavior that they throw things, they hit the other kids, and you have to be on top of them at all times.”

Some of the children have experienced trauma at home and so act at out school, teachers say.

“Obviously it’s not the children’s fault,” said Trenda Jones, 45, the Winston teacher. “But it’s a challenge.”

* * *

As difficult as it is to support and recruit teachers, some Head Start providers say finding quality classroom space in a city that has seen so much decay is even more daunting.

Starfish Family Services, which oversees the Development Centers and two other Head Start programs, has three classrooms sitting empty that could be serving up to 74 children — if only they could get licenses and approvals from city, state, and federal inspectors.

“We have a lot of sense of urgency around getting these classrooms open,” said Brady-Medley, the Starfish Head Start director. “It’s so hard to see they’re still not open and knowing there are children who need them.”

But for months, every time a new inspector has visited the aging buildings where the classrooms are — a large Catholic church and a Salvation Army building — Starfish learned of new problems that generated new expenses and delay. The agency hopes, at last, to open two of the classrooms next month, but it will still have many unfilled seats.

Starfish could arguably open more classes at Winston where there are two unused classrooms now piled with junk, but the former Yost Elementary School is owned by a cash-strapped church that doesn’t have resources to fix the roof or the boiler.

When Development Centers leased the building two years ago, it used $228,000 in federal startup funds to renovate Winston and four other sites. It added a new infant and toddler playground, painted the walls, and redid the floors.

“We were told the heating system was fine, but you don’t know until the winter comes around,” Mallory-Burns said.

Parents were furious when they started getting calls canceling classes on cold winter days. There were 11 days in January and February this year when at least one classroom at Winston fell below Head Start temperature requirements and couldn’t take kids.

“There were some days that were very challenging,” Mallory-Burns said.

Development Centers is looking for a new location but has so far found nothing.

“There are no other spaces in that particular pocket of the city that we could use where we wouldn’t have to spend a bajillion dollars,” Brady-Medley said.

* * *

In a city where the child poverty rate is among the highest in the nation, where 30 percent of mothers have poor access to prenatal care, and where thousands of children are going hungry every day, there are few things that vex early childhood advocates more than the sight of unused classrooms in buildings where children should be safe, learning, and eating healthy meals.

That’s why the city’s philanthropies have banded together to try to address the hurdles now preventing programs from expanding.

"The depths of poverty and the depths of long term disinvestment that’s happened in Detroit for decades, you can’t really match that in Houston or Miami or some of the other cities where Head Start operates."

The 10 foundations in the Southeast Michigan Early Childhood Funders Collaborative, which formed in 2010 out of a more informal conversation, have poured $54 million into early childhood programs between 2012 and 2015. During the federal shakeup of the city’s Head Start program, that collaboration led to an eight-foundation Head Start Innovation Fund that has spent $5.9 million to help agencies respond to the demands of the changing program.

But the foundations have learned that money alone is not enough. They’re also doing strategic planning, convening monthly “learning” sessions to identify problems, and bringing non-profits, foundations, and government agencies together to solve them.

When Head Start centers said they were having trouble spreading the word about new programs to families in the neighborhoods they serve, the Innovation Fund began a citywide enrollment campaign that helped increase the percentage of occupied Head Start seats from 71 percent in March 2015 to 84 percent last month.

“It’s unusual for the foundation community to be running an enrollment campaign, but that was what the agencies told us they needed,” said Katie Brisson, vice president of the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan.

This month, the fund announced another round of funding largely aimed at helping Head Start agencies recruit and retain early childhood educators.

The Fund released a report spelling out a “Head Start Talent Strategy” that proposes ways to increase salaries, give teachers leadership opportunities, and make it easier for educators to get the training they need and find available jobs.

These conversations have led to initiatives from individual funders, including the Kresge Foundation, which this year announced a $20 million five-year push to build new centers, help existing centers make repairs and develop other strategies for growth.

The coordinated push takes a page from other recent philanthropic efforts to solve Detroit’s vexing problems. The region’s foundations have come together around boosting the economy, helping the families of Flint in the wake of the water crisis, and engineering the “Grand Bargain” that pulled Detroit out of bankruptcy.

“It’s a new way of working in many ways,” said Wendy Jackson, the interim co-managing director of Kresge’s Detroit program. “What foundations are doing is coming together in the spirit of collaboration to highlight that the young children in this city are a significant priority. We’re not only putting our resources on the table but also … putting a spotlight on ways to get effective problem-solving under way.”

That unusual coordination is catching the attention of early childhood advocates across the country. “I would go as far as saying it is extraordinary,” said Jeffrey Capizzano, the president of Policy Equity Group and a former senior policy advisor for early childhood development at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Capizzano, who works as a consultant to some of the foundations in the collaborative, said early childhood programs in most cities are paid for with a hodgepodge of state, federal, and philanthropic funding streams without much, or any, coordination.

“In a lot of cities, there’s no one. All those funding streams have different eligibility and workforce incentives and it’s up to the community to try to put it together or not,” he said.

“This is the philanthropic community stepping up in a big way in Detroit. … They’re in there, trying to help.”