When the school year began at Detroit’s Central High School last month, a beloved teacher was missing.

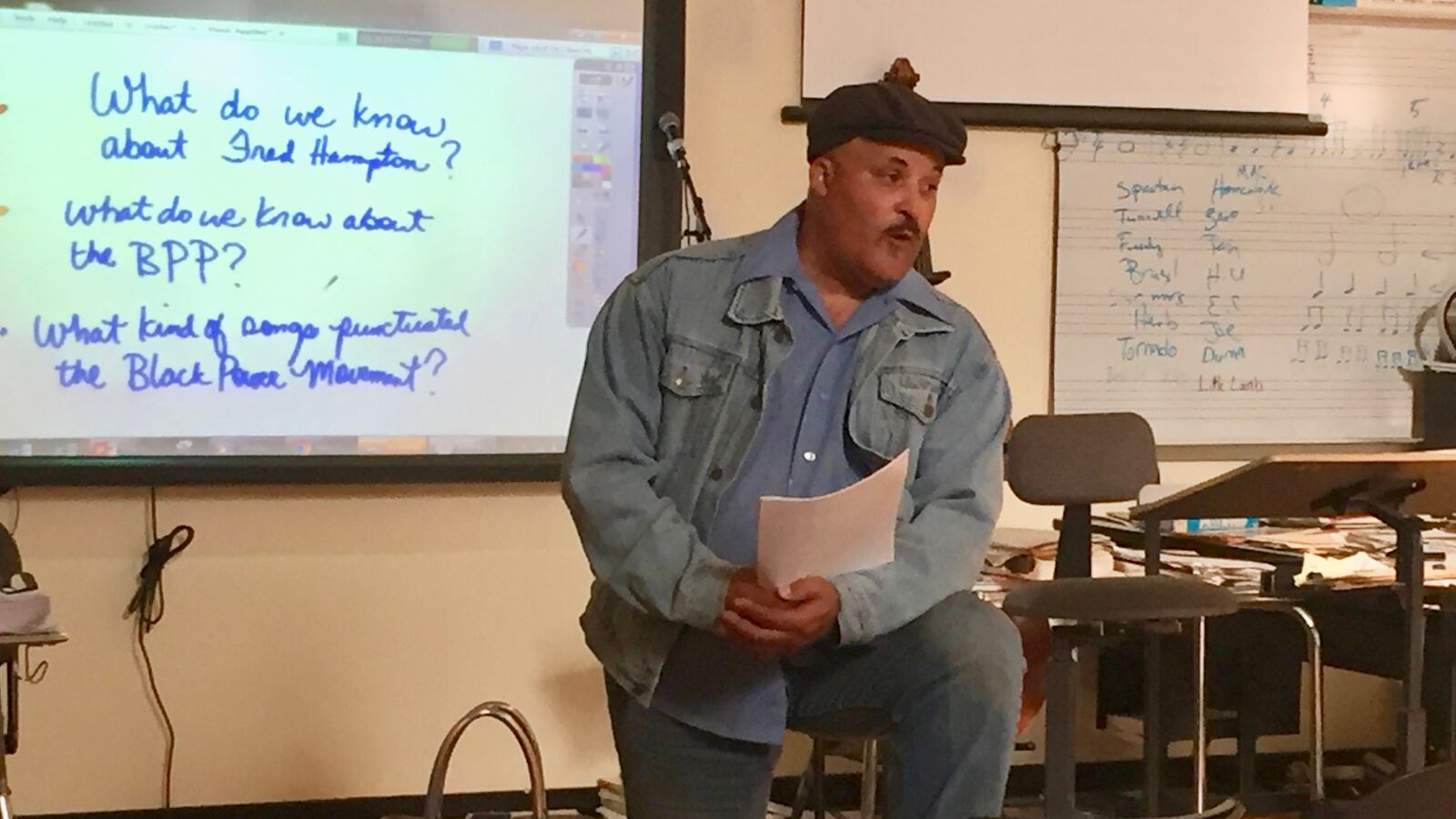

Quincy Stewart, who was featured in a June Chalkbeat story about his innovative use of music to teach students about African-American history, had been determined to stay at Central.

“I do this is because I’m a black man and these are black children,” he told Chalkbeat last spring. “These children have been robbed by this system from the cradle until right now … And when they walk in my classroom, all I feel is love for them.”

But love, unfortunately, doesn’t pay the bills.

Stewart was one of scores of teachers in the Education Achievement Authority, the now-dissolved state-run recovery district, who faced massive pay cuts when their schools reverted to Detroit’s main district in July.

In Stewart’s case, that pay cut came to $30,000 — more than a 40 percent reduction to the $72,000 he made last year.

“They put me in a position where I had to make a decision between being able to pay my bills and staying dedicated to the students that I was there to serve,” Stewart said. “People in the central office are making $200,000, $160,000 and they’re paying us, seasoned teachers, $38,000? I’m in my 50s! That’s Burger King money!”

Stewart, who was also featured in a DPTV broadcast this summer, said he felt he had no choice but to accept a higher-paying job in the suburbs.

“It was a hard decision but I had to go where I could at least pay my bills,” he said. “It’s very easy for people to sit on the sidelines and judge that, but … I would have literally had to work there and work a part-time job just to survive.”

Stewart is one of dozens of EAA teachers who did not return to their jobs this year — a major reason why Detroit’s main district is still struggling to fill 150 teacher vacancies.

The district says that nearly a third of those vacancies are in 11 former EAA schools — even though those schools account for a small portion of teaching positions across the district’s 106 schools.

With those jobs unfilled, some students are in classrooms led by non-certified substitutes. Others are missing out on programs like the one at Central. The school is not currently offering music at all.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said the district is working to aggressively recruit teachers. He told Chalkbeat last week that he is talking with the city teachers union to negotiate incentives for teachers in “hard to staff” positions. But that program will prioritize special education teachers and those who teach core subjects like reading and math. It won’t help fill Stewart’s position at Central.

“We have to make decisions … based on where the challenges are greatest,” Vitti said.

The pay cuts imposed on teachers from former EAA schools is only partly driven by the fact that the union-negotiated pay scale for teachers in the main district is lower than what many EAA teachers had been making.

Another factor was that the new teachers contract, signed by the union and district this summer, offers educators who come in from outside the district just two years of salary credit regardless of their experience.

That’s far less than some Michigan districts where teachers can change jobs without giving up pay. And it’s a different policy than the EAA used. The recovery district had paid teachers more if they came in with experience in other schools.

Vitti says he regrets that senior teachers in the EAA faced steep pay cuts but the main district had to consider teachers who’ve endured years of pay cuts and wage freezes in Detroit schools.

“We can’t just increase pay for a group of teachers that are coming in from the outside,” Vitti told Central’s principal Abraham Sohn on the first day of school as the two walked by the school’s empty band room where Stewart used to teach. “That doesn’t send the right message.”

Vitti has vowed to raise teacher salaries in the near future, calling that a priority for the district.

Someday, Stewart said, wages might be high enough that he’ll consider returning to Detroit. But for now, he’s committed to his new job at Harper Woods High School, just east of the city, he said. He urged the district to find a way to increase pay for all of its teachers.

“If they really truly cared about having seasoned, quality teachers, they would make an effort to pay them,” he said. “Even a teacher with a doctorate is only going to make maybe $60,000 and that’s just preposterous. You owe more in student loans than you make in salary.”