Three months after taking on one of the most daunting tasks in American education, Nikolai Vitti was having a fit over pizza — $340,000 worth of pizza.

Vitti, Detroit’s new school superintendent, had just discovered that the district had set aside that eye-popping sum of money last year to pay Domino’s Pizza for what he assumed were hundreds of thousands of slices for parties in schools.

He was asked if he wanted to do the same for next year.

“Do you really think for a minute I’m going to bring a contract to the board at $340,000 for Domino’s?!” he asked an aide. “That would be like — ‘Here — write a front page story about how inefficient this district is.’ Are you insane? Are you really insane!?”

In his first months on the job, Vitti had seen what he described as a shocking lack of basic financial and academic systems in the district. He’d seen contracts that were nonsensical, payments that had slipped through the cracks. He knew of principals who’d apparently given up on getting support from the district and had turned to a brand of survivalism to get what they needed for their schools.

“It is truly a district that has been mismanaged for over a decade,” he says.

But even by the standards of what he’d seen so far, the pizza contract seemed extreme.

“I love the explanation on why we need a Domino’s contract because it’s wholesale, right?” Vitti vented to an aide. “To reduce the price? And then everything else we do we have 700 vendors?! We decided to get it right for pizza but we didn’t get it right for toilet paper?”

But a day later, something surprising happened with that pizza contract.

As Vitti convened a meeting with top advisors, he learned that the Domino’s contract was not actually for parties. It was for a special pizza that Domino’s had created for schools called a “smart slice” that uses whole wheat flour and lower amounts of fat and salt to give kids a healthy alternative to less-popular lunch offerings.

That’s when a contract that Vitti had been lambasting for days became an inspiration.

“If we’re using Domino’s as a way to incentivize kids to eat … then why not do a bid for Chinese food?” he asked.

“Or Subway,” an aide suggested.

“We could get local businesses,” Vitti said. “A ton of local businesses! As long as they meet the nutritional value. … Think of all the things we could do with a Detroit small business connection to it!”

In fact, Vitti said, “if we really want to talk big, in every high school, you could have kids that are working to prep food and all that.”

“See,” he told his advisors gathered in a conference room adjoining his office in the district’s headquarters in Detroit’s iconic Fisher Building. “We went from Domino’s to a complete conversation about innovation. That’s why you have to have the conversation.”

* * *

Improving on pizza contracts might not seem like the kind of thing that can fix a school district like Detroit’s.

The schools here, which have some of the lowest test scores in the country, have become a national symbol of educational crisis. They remain the largest roadblock to the city’s resurgence nearly three years after its emergence from bankruptcy. The heralded improvements in the city’s downtown have had virtually no effect on its schools.

But Vitti, the 40-year-old father of four who took over the Detroit district last spring, has promised not just to improve the district’s 106 schools. He says he can transform them.

“We’re going to make this the best urban school district in the country,” he says in speeches and interviews.

He knows the odds are stacked incalculably against him — he felt it on the first day of school, when the system had 250 teacher vacancies, despite his public commitment to fill every position.

But he’s determined to give Detroiters something they haven’t had for their schools in a generation. He’s promised to give them hope.

If he’s going to do that, he says — or if he’s at least going to make some progress in that direction — he has to look for ideas in places like pizza contracts, where other leaders might see little potential for change.

He has to move beyond what he calls “compliance thinking” where decisions are made only to conform with legal requirements, to try to imagine a different future for the district.

And he has to do that while simultaneously attempting to bring order to a system that he describes as in total disarray.

Much of that disarray is well known: buildings that are crumbling and dirty; a severe teacher shortage that has robbed children of quality instruction; conditions so dismal that a federal lawsuit last year alleged they violate Detroit children’s right to basic literacy.

The district’s reputation has been so ravaged among Detroit parents that tens of thousands of families have fled the district for charter or suburban schools in recent years — fueled in part by the liberal school choice laws in Michigan that were promoted by Betsy DeVos before she became U.S. education secretary.

The exodus of families had left the district in such dire financial straits that it only avoided bankruptcy last year when the state put up $617 million to create a new district called the Detroit Public Schools Community District.

But those are just the problems you can see from the outside. Vitti understood them well before he left his job in May running the schools in Jacksonville, Florida, to take over the schools in his hometown. [He’s from nearby Dearborn Heights.]

On the inside, Vitti has discovered that the district he’s inherited is utterly broken.

“I mean we lack the systems for everything!” Vitti says. “Everything! For hiring teachers, onboarding teachers, paying teachers, ordering books, adopting books, cleaning buildings, seeing contracts, what contracts there are, how they’re executed, why they’re executed, what they’re used for, what they’re not used for.”

* * *

Since arriving in Detroit last spring, Vitti says he’s seen “pockets of excellence” in schools where devoted teachers have managed to weather years of turmoil and decline.

But when he talks about the the district’s central office, he becomes visibly angry.

What makes it all so infuriating, he says, is that the men from whom he inherited the district were supposed to be financial experts.

The state of Michigan had seized control of the district in 2009, citing a financial emergency, and installed a series of financial managers — five different men — who ran the district for eight years until the new school board took over in January.

The loss of local control had been painful for Detroiters.

A school board chosen by voters had been rendered largely impotent while the men running the district had slashed teacher pay and shuttered dozens of schools with minimal community discussion. The closings accelerated enrollment declines — fewer than half of Detroit children remain in the district — and left some city neighborhoods without any schools at all.

As an educator who worked as a teacher in North Carolina and New York City before entering a PhD program at Harvard University that trained urban superintendents, Vitti says he’s not surprised that the emergency managers didn’t get the academics right.

But you’d think they’d have figured out the nuts and bolts, he says.

“At a minimum, you would think an emergency financial manager would know nothing about education but would focus on systems and processes because that’s what Detroit lacked,” Vitti says. “And what I actually see is, you know, walking into this district, there was no vision for how a district or a central office supports schools.”

Example: The district promised bonuses to teachers who took hard-to-staff positions last year but, somehow, the bonus checks didn’t arrive when they were supposed to.

“It was frustrating,” says teachers union leader Ivy Bailey. “They were calling us asking, what’s the problem? And we didn’t know.”

The problem, Vitti learned, was that “the left hand had no idea what the right hand was doing. This was negotiated by labor relations. It was somewhat understood by HR but then finance wouldn’t know about it.”

Another example: Here in a district where the teaching shortage has meant children have gone months without a certified math teacher, people who applied for jobs weren’t getting hired.

“We had teachers, let’s say at the job fair, that had committed to joining the district,” Vitti says. “That teacher leaves the job fair thinking that they’re going to Denby [High School]. The principal thinks the teacher is going to Denby and then no one’s followed up with the teacher.”

The teacher eventually gets an offer from another district and takes that job instead, he says.

The examples go on and on.

The central office took so long to approve expenses that principals had taken to buying things on their own. That led to corruption and to inefficiencies that Vitti’s team is uncovering, like the seven schools that all used the same online learning tool last year.

No one negotiated a multi-school discount so every school paid full price, Vitti said. And the schools weren’t in contact to determine if a different program might have been better.

“We shouldn’t be using anything at just seven schools unless it’s a pilot,” Vitti told members of his cabinet as they gathered for a meeting in his office. “And if we’re going to do pilots, then they should be free and there should be a whole lot of principal buy-in as to why they’re being used.”

The last emergency manager, Steven Rhodes, declined to comment on the substance of Vitti’s criticism, sending a statement saying only that he wishes “Dr. Vitti and the entire staff at DPSCD the very best in meeting the challenges of educating its students.” The governor’s office and State Treasury Department, which appointed and oversaw the emergency managers, did not respond to requests for comment.

Cleaning up systems is essential if Vitti wants to take the district in a different direction, says Robert Peterkin, the Harvard professor who, for 20 years, led the urban superintendents program where Vitti earned his PhD.

“What he’s got to do is establish these basic procedures while educating all the kids,” Peterkin says. “I know that sounds impossible but these systems don’t have to be invented. …Those things are not rocket science. Recruitment of teachers. We know how to do that. We know how to have a contract system. We really do. We just need to have somebody who’s going to go out and get it done.”

But Vitti says the mismanagement infuriates him “because it limits what you can do now.”

“That not only hurt the city, it hurt children and it hurt public education and now we have to make up for the sins of the past while still moving forward and creating results, which is daunting,” he says. “It’s possible, but daunting.”

* * *

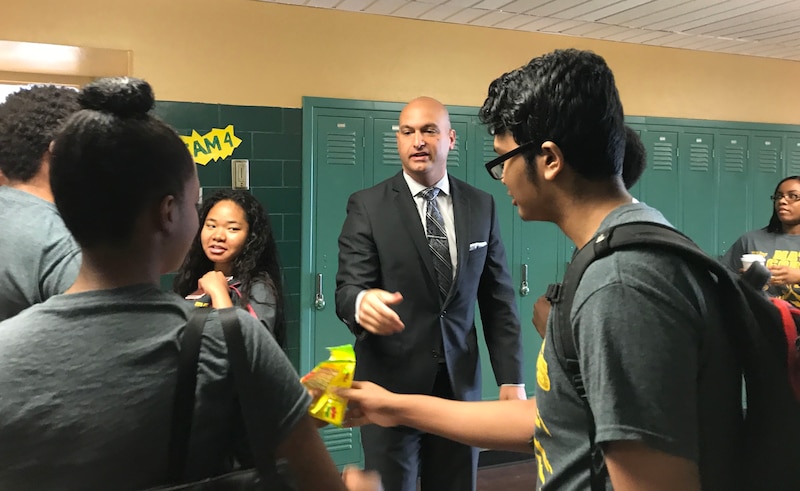

If Vitti is daunted privately, he betrays little hint of concern as he travels around the city.

He gives confident speeches and interviews — typically from the gut, without using talking points or prep materials — that are filled with promises for the kind of wholesale improvement that seems unlikely in a nation where the box scores for urban superintendents show far more losses than wins.

He’s hardly the first superintendent to arrive in a city making grand predictions for the future.

“The idea of the school superintendent as the person who can fix it all is at least as old as the 20th century,” says David Cohen, a professor of educational policy at Harvard University and the University of Michigan.

But superintendents are largely powerless to address things like residential segregation and fiscal inequality that helped destroy urban schools in the first place, Cohen says. “The problems in [urban schools] have been created by decades of government policies …There’s no way that the educational problems in these systems can be solved by any particular superintendent.”

In Detroit, he says, the challenge is even greater. “Detroit just faces huge problems and many of them are not of the district’s making and are not within the district’s control.”

Yet Vitti says he plans to put nearly every waking hour he has into the effort.

He sleeps just three hours most nights, sometimes cranking out emails until 3 a.m. before catching some winks until dawn, he says. Other nights, he’ll go to bed early, around midnight, and wake up at 3 a.m. to respond to emails.

“We have to manage [the district] and transform the district at the same time and that requires a different work ethic and energy level,” he says.

Vitti doesn’t expect his aides or advisors to put in those kinds of hours, but he has little patience for anyone who isn’t moving with as much urgency as he is. He stacked his team with people he trusts to keep up the pace, firing dozens of longtime school officials and technocrats and replacing many with people he knew from his days working in Florida.

“Tick, tick, tick,” he chided an aide when she reported that she hadn’t yet made an important hire.

“I’m working, working, working,” she responded. “I thought I found somebody but they’re not interested.”

Despite his sometimes abrasive tone, Vitti is not outwardly combative. Unlike some superintendents who’ve blazed into districts on a promise to push out bad teachers or to jump start performance by shutting down schools, the words he speaks in Detroit are largely the ones that parents and community leaders want to hear.

He talks of the “whole child,” and finding ways to meet children’s social and emotional needs instead of just drilling them on standardized tests. He talks of “parent engagement” and community partnerships. And he and his wife have enrolled their four children — including two who have special needs — in a district school.

Vitti spent his first months in Detroit on a listening tour, meeting with parents, teachers, students and community leaders to assess the needs of the district.

When teachers complained that students were spending too much time taking tests, he reduced mandatory student testing. He also promised to raise teacher pay.

And he’s paying attention to what students learn, something that he says has been neglected. He’s pushing a district-wide curriculum audit to make sure Detroit kids are getting an education that meets national standards. And he wants a teacher evaluation system, based on research, that supports teachers and helps them hone their craft.

If Vitti is successful, the tone he sets now will be why, said Peterkin, the Harvard professor who helped guide Vitti through his doctorate.

“I don’t think that any modern superintendent can see themselves as a do-it-all, know-it-all, great man theory kind of leader,” Peterkin says. “He needs a team. He certainly needs the school board. He needs community support. He needs to not have anti-public school voices tearing him down. He needs strong parental support and a business community that wakes up and realizes it needs its public schools but I think he can lead that effort.”

* * *

In the three days that this reporter followed Vitti, he zig-zagged around the city, giving speeches, meeting with potential partners, and directing staff on everything from the best way to measure the condition of school facilities to whether or not a PowerPoint presentation for a school board meeting should have photos or bullet points.

He doesn’t take notes in meetings and yet seems to keep countless details about contracts, personnel — even the calorie counts of his favorite snacks — in his head.

And while he’s listening to briefings, he’s also searching around for new ideas.

During a meeting about creating internships for students at a district vocational school, he spotted the school’s slogan — ”where great minds are developed” — and pointed it out to a school board member, Angelique Peterson-Mayberry, who was sitting with him.

“What do you think about our logo for the district: Where Detroit Minds are Developed?” he asked her. “Or where Detroit Minds Matter? That’s a good one too. We’ve gotta figure that out.”

And as he met with the heads of a prominent local museum, he came up with an idea for an entirely new school.

The museum execs had largely wanted to discuss bringing more students to visit on field trips when they asked to meet with Vitti. He had immediately signed on, mentioning a “cultural passport” he hopes to create that would enable students to visit an opera, a symphony or great works of art in every school year. But he didn’t stop there.

Sitting in an office upstairs from the museum’s exhibit halls, a grander, more ambitious idea seemed to pop into his head.

“What about a deep partnership with a K-8 school?” Vitti asked. “Something similar to a magnet school?”

The museum and district could team up on “deep training for the principal and teachers,” he said.

The school could build on the museum’s exhibits to teach art, history and other subjects.

“Imagine everything our students could experience!” he said.

The museum execs seemed stunned — but delighted — by the proposal.

“We would love that!” one exclaimed.

There are countless logistical and practical details that would have to be worked out before a school like this could be created.

It’s too early to tell whether Vitti has the political skills and financial resources to take any of his ideas beyond the concept phase. The fragile nature of the discussion is why the museum officials asked not to be publicly identified with such a preliminary proposal.

And no matter what he does, Vitti is operating in a tenuous environment. The school board supports him now, but could eventually turn on him. The state has stepped out of Detroit’s school operations, but a new governor could step back in. Those things have happened repeatedly in this city before.

But, in that moment, this idea — and that different future — seemed entirely possible.

“Terrific!” the museum executive said. “This is exactly the kind of work we want to do!”