This story is part of a partnership between Chalkbeat and the nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica. Using federal data from Miseducation, an interactive database built by ProPublica, we are publishing a series of stories exploring inequities in education at the local level.

It was Spirit Week at Renaissance High School, and students in Adam Alster’s sixth-hour Advanced Placement physics class were dressed up as senior citizens and babies. But as Alster reviewed the finer points of velocity graphs, students took notes and asked questions without seeming to notice their classmates’ silly outfits. There was work to do.

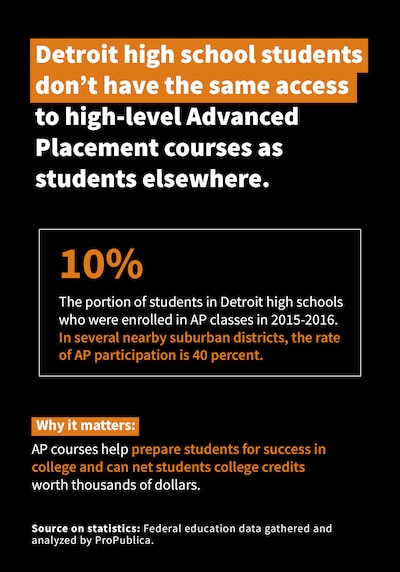

Advanced Placement courses — known as APs — offer some of the most challenging curriculum available to high schoolers in the United States, so much so that many colleges offer credits worth thousands of dollars to students who can master the material. Students in this classroom were keenly aware that their work here would provide a springboard toward a college degree.

They were aware, too, that Renaissance is an island of opportunity in Detroit, where most high schoolers don’t have the same access to AP courses as their peers across the state.

“Some of my friends at other schools, they said, ‘We don’t have AP classes at all,’” said Cierra Cox, a senior who plans to study neuroscience in college. “I was like, ‘What, that’s crazy!’ You should have the right to be able to challenge yourself and see how far you can go with a given subject.”

But her friends are not outliers. About half of Detroit’s high schools, both district and charter, offered no AP classes in 2015-16, according to data that city schools reported to the federal government.

In Detroit schools that offered AP courses, only 10 percent of students were enrolled. That’s compared to neighboring Grosse Pointe, on the other side of one of the starkest socioeconomic borders in America, where 38 percent of high schoolers are enrolled in the higher-level courses.

The federal education data, newly compiled by ProPublica in an interactive database, sheds light on a stunning gap in the opportunities available to Michigan students depending on where they attend school.

While the data will come as no surprise to educators in Detroit, it makes clear the depth of the challenge they face as they attempt to expand AP access in the city.

“There is not equitable access,” said Zach Sweet, a former AP teacher at Renaissance who is now working with the city district on an ambitious plan to offer APs at all of its roughly two dozen high schools.

AP courses in academic subjects from physics to history to art offer curriculum so challenging that it’s considered on par with college coursework. Educators say by that offering AP courses — and preparing students to take them — schools are taking powerful steps to prepare students for higher learning.

However, years of financial challenges, relentless student turnover, and disappointing test scores in both district and charter schools have put APs out of reach for most schools in Detroit, where eight in 10 students are black and over half of all students are from low-income families.

Schools in the city are already under extreme pressure to increase their lowest-in-the-nation test scores, making them less likely to focus on their top students, said Agustin Arbulu, director of the Michigan Department of Civil Rights.

“You’re really fighting to meet certain score levels that the state has set,” he said. “And when you look at scores, what do you look at? The median. So you put your dollars there.”

What’s more, AP courses take extra time and money, two things that have been in short supply in city schools that have spent much of the recent decades fending off one crisis after another.

College Board, the non-profit that certifies the rigor of AP courses and administers exams that measure whether students have mastered the material, estimates that it costs between $2,000 and $10,000 to start a new AP course, depending on the subject. Most of the money goes to up-front costs like textbooks and scientific equipment, while some pays to train teachers who are new to the advanced curriculum.

Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, who assumed control of the city’s main district last year, has sought to expand access to higher-level courses like APs. And Renaissance is serving as a de facto campaign headquarters.

With more than one in five of its students enrolled in at least one AP class in 2015-16, it was already beating the state average for AP access, but its AP program is growing quickly. Over the last year, it added an AP computer science course, and the number of AP exams passed by Renaissance students increased from 52 to 118.

At the same time, Renaissance students took but did not pass many more exams, mirroring national trends. Across the country, more black and Hispanic students are taking AP courses and exams every year, but many of them don’t earn passing scores. That means they’re not getting the financial or placement benefits that AP exams could confer, and research is inconclusive about whether their participation has benefits at all.

Kahlid Ali, who took several AP courses at Renaissance before graduating in June, said he benefited from the AP push. Ali, 18, is a standout student: Though just a freshman at Wayne State University, he’s already guaranteed admission into the university’s medical school through a scholarship program.

But it’s not the three AP tests he passed that are helping him most in his transition to college: It’s the one he failed.

Even as he admits that he didn’t study hard enough for the AP Chemistry exam his junior year, Ali says the concepts he learned are giving him a leg up.

“Although I didn’t do well on the test, I learned the lessons,” he said. “To be in college without any APs, you’d really be at a disadvantage.”

His experience is why leaders in the Detroit Public Schools Community District are hoping to spread the strategies that increased AP course access at Renaissance. They’ve asked Sweet to leave his classroom at Renaissance and help train educators to teach higher-level courses and recruit students to take them.

The challenge ahead is sweeping, according to Sweet. “What it would take for this to be successful in DPSCD is a far greater support system, if teachers had great professional development and mentors they could work with regularly,” he said.

For two years, teachers at Renaissance have received regular trainings on AP through a grant from the National Math and Science Initiative, a nonprofit that is also supporting AP programs at two other district schools. The district is also working on a broader plan to increase AP enrollment.

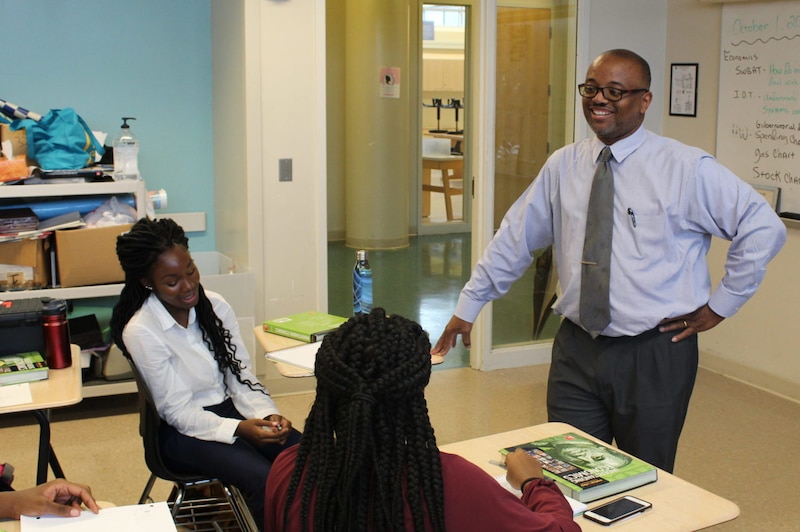

Kevin Smith, a teacher at Renaissance, said AP programs can’t be expanded without extra support for teachers. “I had to start thinking on a different level,” he said of his first year teaching AP Economics.

Once teachers are trained to offer higher-level courses, Sweet is confident that the district can convince students to sign up. Soon, students will begin hearing this message from their peers. Sweet won a $2,000 grant to send his former students to schools across the district to evangelize about AP courses.

Alster, Renaissance’s AP physics teacher, says the number of students taking the AP course and passing the test has “dramatically increased,” an improvement he credits in part to improved salesmanship.

“We’ve been stressing the importance of AP, and how valuable it is,” he said. “Over the long run, this experience is going to pay off.”

A district-wide curriculum overhaul could help, too. A month into the school year, Alster says teachers in the science department at Renaissance are convinced that a new science curriculum being piloted this year at some schools is much stronger, and will produce juniors who are better prepared for AP-level work.

Sitting in a circle with economics textbooks on their laps, four juniors at Renaissance said higher-level courses should be available to every student in Detroit. Without challenging courses, they worried they wouldn’t be able to meet their life goals. Two wanted to be surgeons — orthopedic and cardiovascular — and all planned to apply to selective schools like Spelman College or the University of Michigan. Among them, they planned to take more than a dozen AP courses before graduation.

“I think it should be offered to everyone,” said Madinah Hart, of advanced coursework.

“It helps a lot,” said Natasha Rice.

Caitlyn Cutler agreed: “Everybody should get the opportunity to get that step ahead.”