Faced with a looming Supreme Court decision that could adversely affect unions, some labor leaders from across the country are looking to Michigan for a way forward.

“We’re constantly deluged by staffers in non right-to-work states,” said David Crim, a spokesman for the Michigan Education Association, the public teachers union. “They ask, ‘how did you stay alive?’”

Michigan’s legislature passed so-called right-to-work legislation in 2012, dealing a blow to the coffers and membership of public sector unions, including those that represent teachers.

At issue are the fees paid by all workers, including those who are not unionized, in some union workplaces. The fees cover services, such as legal representation, that are provided by the union to every worker regardless of their membership status. In right-to-work states, such such mandatory contributions are prohibited.

Now, the Supreme Court is expected to hand down a decision in Janus v. AFSCME that would expand right-to-work to the 22 states where it doesn’t already exist.

The plaintiff in the case is Mark Janus, an Illinois state employee who says he shouldn’t have to pay union fees because he disagrees with the political activities of the union that represents his workplace, AFSCME. He filed suit in 2015 to overturn a legal precedent established in 1977, in Detroit, when the Supreme Court ruled in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education that these fees were constitutional.

Detroit’s teachers union, which recently negotiated for its members $30 million in bonuses and salary increases, is evidence that teachers unions won’t likely disappear even if the Supreme Court votes to expand right-to-work. But drops in union membership — MEA saw a 25 percent decline — have some observers looking to Michigan to understand the possible implications of Janus.

“We’re already in a post-Janus world,” Crim said.

Before the law went in to place, union dues could be deducted directly from teacher paychecks. That’s now illegal, so Ivy Bailey, president of the Detroit branch of the American Federation of Teachers, said she has become a dues collector in addition to her other duties.

Despite devoting a “big part” of her time to collections, she said that teachers are less likely to pay for union membership when it doesn’t happen automatically.

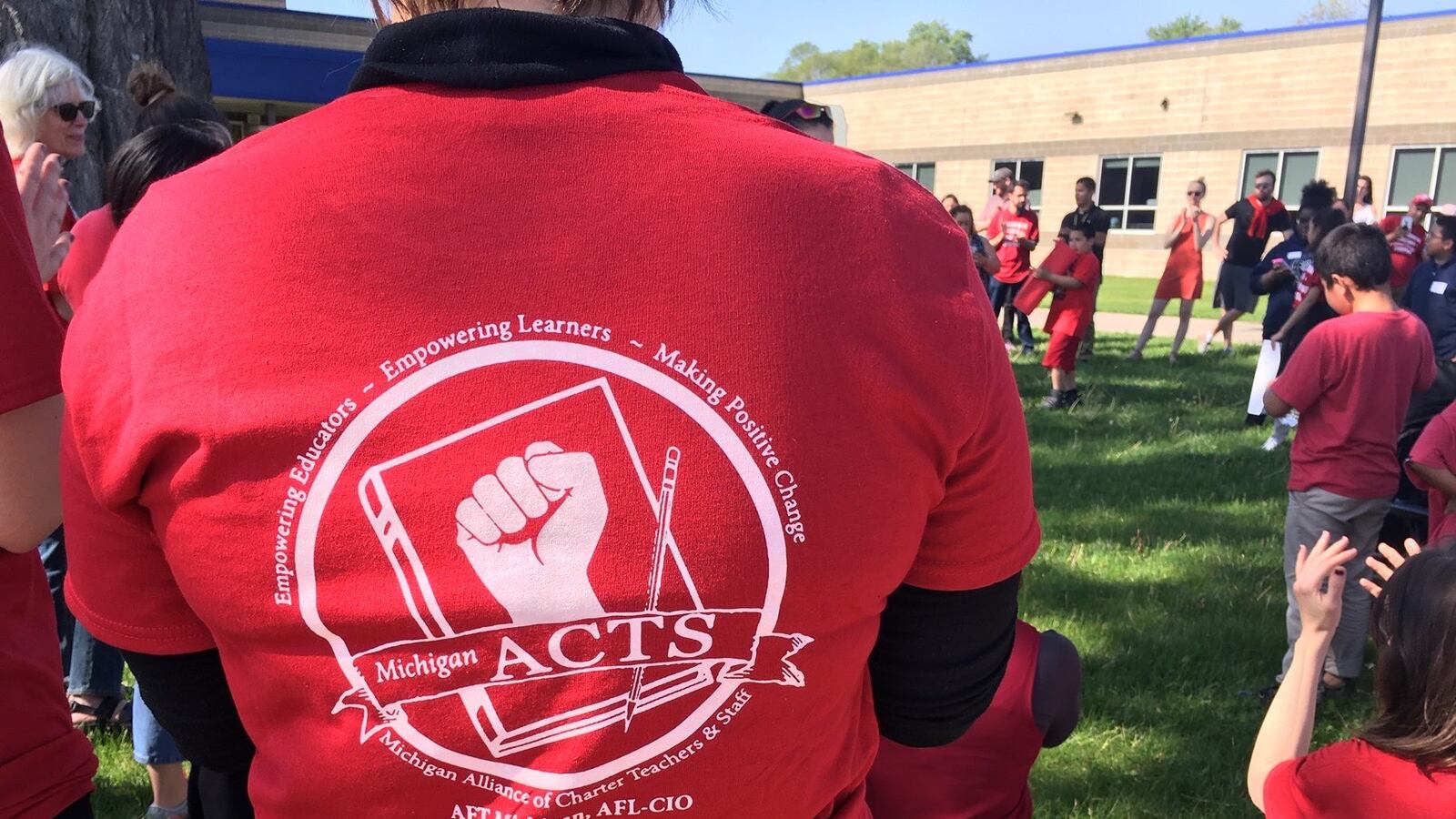

That’s why unions in Michigan have ramped up their efforts to recruit teachers, and why unions in states that could be impacted by Janus are preparing to do the same.

If a ruling in favor of Janus has any impact in Michigan and other right-to-work states, it will be indirect. Problems for national teachers unions could mean trouble for local affiliates, which receive some funding from their national umbrella group. In Detroit, such funding is minimal.

The National Education Association, of which MEA is a subsidiary, expects to lose about 10 percent of its members and $50 million in revenue if the Supreme Court rules in favor of Janus, according to a report published in the 74.

In this scenario, the national union “would certainly downsize, as would revenue and support that we receive from NEA,” Crim said.

Regardless of the Supreme Court’s decision, teachers unions won’t be disappearing any time soon. The Michigan Education Association remains the largest public union in the state with about 140,000 members, and has said that membership has stabilized and may even be growing.

When right-to-work passed in Michigan in 2012, legislators “felt that would destroy unions in Michigan, specifically us, Crim said. “That hasn’t happened.”