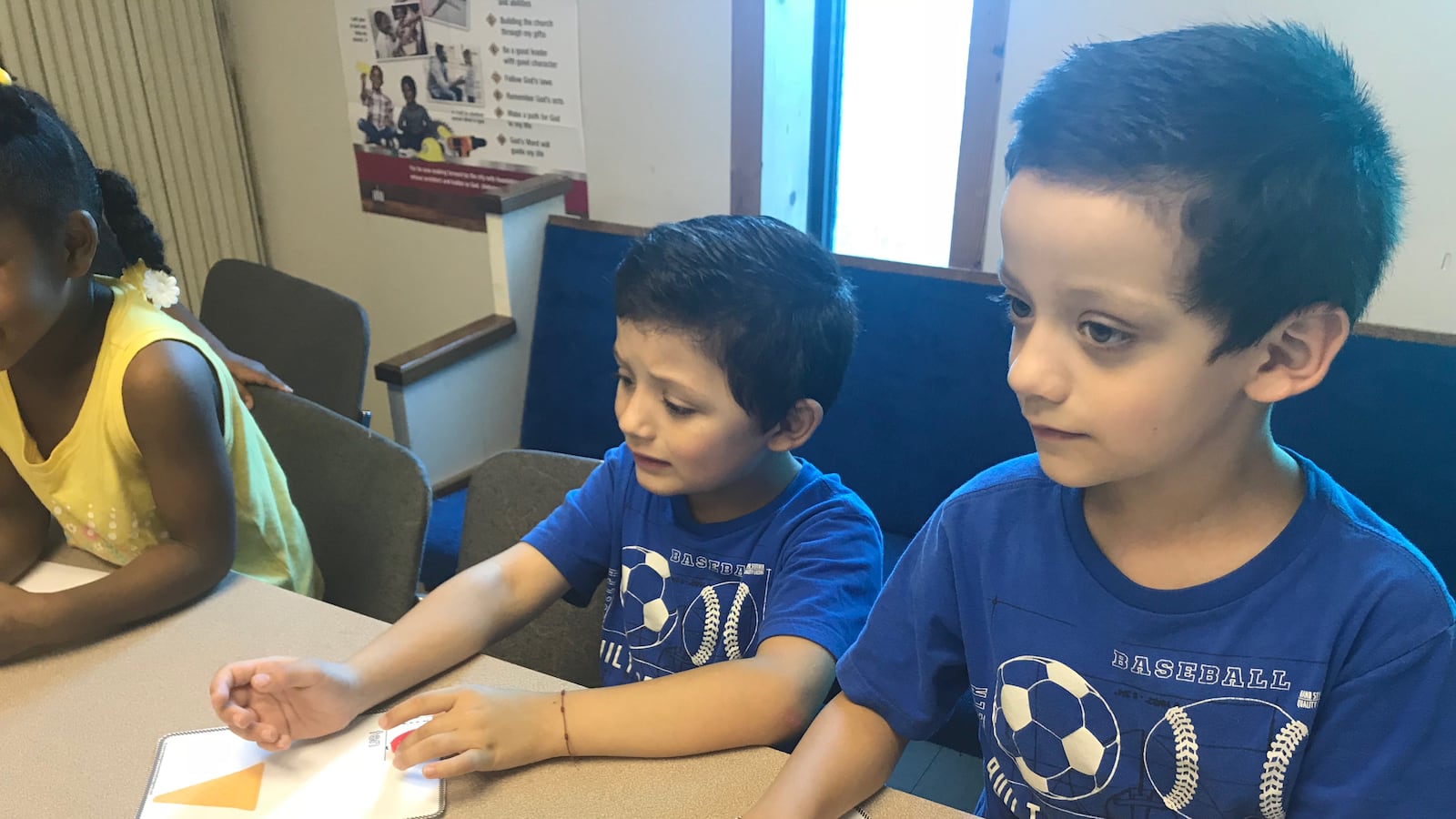

In a back room of a church on the city’s near east side, Abraham and Magaly Gonzalez attended a summer camp with their 5-year-old twins. Six other children from the church’s child care center were seated around a rectangular table lit by fluorescent overhead lights, working on exercises to teach them colors, numbers, and shapes.

“They have to learn more,” Magaly Gonzalez said, explaining that the couple has been working with the boys, Rafael and Nicholas, at home using books and videos, “and we have to learn more to help them.”

This was their second session in the Detroit main district’s newly launched Kindergarten Boot Camp, a four-week summer program led by district staff that focuses on the basics children need to start school. The Gonzalezes sent their sons to preschool when they were 4 years old. But the couple was so excited about what their boys learned in an earlier camp that they came to the People’s Missionary Baptist Church, a community site, to help them learn more: how to count to 20, spell and write their names, and recognize letters and shapes.

Although school readiness is not a new notion for educators, in the past couple of years, the summer programs for children who are about to start kindergarten have become a national trend, said Robin Jacob, a University of Michigan research associate professor who focuses on K-12 educational intervention.

“They are a fairly new idea, and they are important,” said Jacob, who researched more than a dozen similar programs that recently have sprung up from Pittsburgh to Oakland, Calif., many targeting children who had no prior preschool education.

A full year of preschool is the best way to get children ready for kindergarten, she said, “but we know there are kids who fall through the cracks and it’s important to catch those children, and preschool doesn’t always include parents so they learn how to help their children at home.”

A growing number of districts and schools have added the programs, recognizing that they last only a few weeks, are relatively inexpensive, and keep students engaged during the summer months, she said.

These early lessons are important for children and their parents, said Sharlonda Buckman, the Detroit district’s assistant superintendent of family and community engagement, because officials too often hear from teachers that children don’t know how to sit in their seats, line up, or hold a pencil.

Even when they’ve gone to preschool, she said, some children still have trouble, because kindergarten requires more discipline and structure than preschool. The children’s parents often don’t know how to prepare their children for kindergarten and lifelong learning.

That’s why the district’s program requires parents like the Gonzalezes to attend the boot camp sessions with their children.

“People automatically assume Kindergarten Boot Camp is about the kids,” Buckman said. “For us, it’s about the parents.”

About 100 parents attended the classes this summer in nine elementary schools and the church to build on the belief that “parents are the child’s best teacher,” Buckman said.

Parents also are involved in programs sponsored by Living Arts, a nonprofit arts organization, that is offering a range of programming in Detroit through Head Start to help preschool children and their parents get ready for the first day of school.

“Our movement, drama and music activities encourage children to learn how to be part of a line to transition to another part of the day such as going outside, the bathroom or a circle,” said Erika Villarreal-Bunce, the Living Arts director of programs. “The arts help children understand this new space they’re in is not like things were at home, and helps children learn to function in those spaces.”

Although not all camps require parent involvement, they offer similar lessons to prepare children for kindergarten.

In suburban cities such as Southfield and Huntington Woods, the Bricks 4 Kidz program uses models made of brightly colored bricks to teach preschool children letter recognition, patterns, colors, counting, and vocabulary. Maria Montoya, who works for the charter school office at Grand Valley State University, the city’s largest charter school authorizer, said Detroit charter schools have offered a range of options over the years including week-long and single-day programs to help kids get ready for kindergarten.

The best of them teach basic academics, instruct children in a classroom setting, and engage parents in student learning, Jacob said.

“Educators have thought about school readiness for a long time, but understanding how important that summer transition period can be is something that people have started to think about more carefully recently,” she said. “Summertime is a key time where kids can be learning.”

Regina Bell, a W.K. Kellogg Foundation program officer, said the foundation funded Detroit’s Kindergarten Boot Camp because of the importance of focusing on the earliest years of life to ensure students’ success in K-12 and beyond.

“Part of this is recognizing that most of the the human brain is developed by the age of 5, and when you think about early learning opportunities, those are the foundation for the future,” she said. “It is that foundation that really takes children into the K-12 system.”

Kindergarten Boot Camp, funded by a $3 million Kellogg grant, is only one part of the Detroit district’s efforts to increase parent involvement to improve student attendance, discipline issues, and test scores. The three-year grant also funds the Parent Academy and teacher home visits. (Kellogg is also a Chalkbeat funder).

As for Abraham Gonzalez, the twins’ father, parenting and teaching children doesn’t come naturally. So he says the early learning opportunity for his sons is essential for them — and their parents, although they spent a year in preschool at the Mark Twain School for Scholars in southwest Detroit.

“We are trying our best to teach these kids,” he said, and it’s even more challenging teaching them when Spanish is their first language.

Now, he said, the boys’ are getting so proficient at English, they understand more than their parents.

“They are understanding what the people tell them,” he said. “Sometimes, we don’t.”