On its face, the public forum Thursday night was about candidates for Detroit school board. In fact, the night belonged to the citizens.

Early in the evening, a tableful of Detroiters — most of them graduates of Detroit public schools, all of them concerned about the future of Michigan’s largest school district — set about deciding what they wanted to ask the candidates during a series of Q&A sessions that CitizenDetroit, which co-sponsored the forum with Chalkbeat, called “speed-dating.”

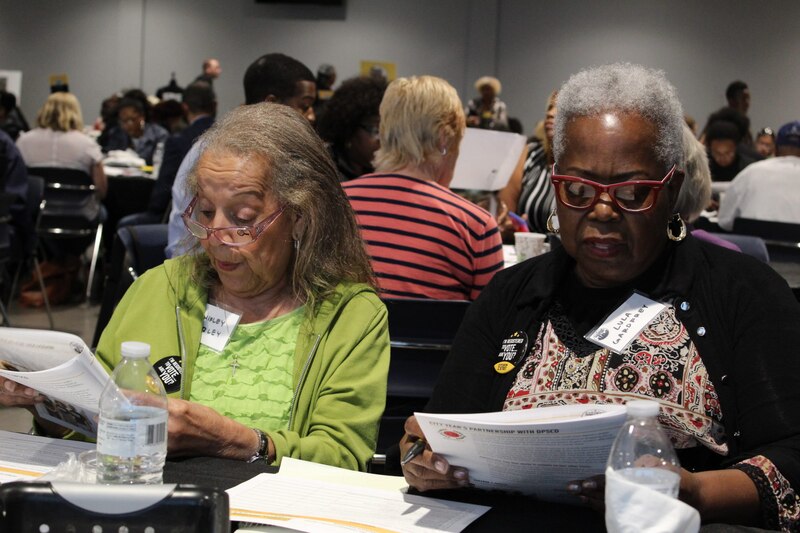

Shirley Corley, a first-grade reading teacher who retired from the city’s main district, honed in on the state’s “read-or-flunk” law, which could force schools in Detroit to hold back many of their third graders next year if they can’t pass a state reading exam.

“I heard that one on the TV, and I couldn’t believe my ears,” she said.

As a gong sounded, she hurried to shape her outrage into a question: “What are your plans about holding back third-grade readers, and why aren’t they reading better?”

Then Terrell George, one of the candidates for two openings on the school board, sat down across the table. She asked her question.

All across a packed union hall in Detroit’s historic Corktown neighborhood, similar scenes were playing out. Candidates rotated between tables, where they sat face-to-face with roughly 10 Detroit residents armed with prepared questions and many lifetimes-worth of combined experience with the city’s main school district. Every five minutes, someone hit a gong, and candidates got another chance to lay out their vision for the troubled district and impress the voters who will decide their future at the polls in November.

It is Detroit’s first school board election since the board regained control of Michigan’s largest district, which was run for nearly a decade by state-appointed emergency managers. And it marks a crucial milestone in the district turnaround effort led by Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, whose reforms have so far enjoyed the board’s support.

(Six of the nine candidates attended the event. Deborah Lemmons and M. Murray [the full name listed on the ballot] didn’t respond to an invitation, according to CitizenDetroit. Britney Sharp said she had a scheduling conflict and was unable to attend.)

From Natalya Henderson, a 2016 graduate of Cass Technical High School, to Reverend David Murray (his legal name), a retired social worker and minister who previously served a long, sometimes controversial stint on the school board, a broad field of candidates are vying to help steer a district through a historic turnaround effort. The winners will help decide what to do about the $500 million cost for urgent school renovations and test scores that are persistently among the worst in the nation.

(Click here to watch the candidates introduce themselves in two-minute videos, and here for short bios.)

The low scores are the reason the state’s third-grade reading law, which calls for students reading below grade level to be held back, will disproportionately affect Detroit. But at Table 1, Corley gleaned some hope from George’s answer to her question about the law. He said more attention should be paid to early literacy instruction: “We must start from the beginning in preschool and kindergarten.”

Corley shook her finger in approval: “That’s right.”

On the other side of the table, Viola Goolsby wanted to know how George would respond if the state attempted to close the district’s lowest-performing schools.

“I would be opposed to any school shutting down any school in any district…” George began.

Then the gong sounded. “That was quick,” George said, standing up.

The table had a five-minute break — with roughly 130 people in the room, there were more tables than the six candidates who attended — and then another candidate, Corletta Vaughn, slid into the seat reserved for candidates.

Lewis EL, a realtor who works in Detroit, read a question from the list provided by Chalkbeat and CitizenDetroit, the non-profit that hosted the event: “What are the pros and cons for the district in collaborating with charters and suburban school districts?”

Vaughn’s voice fell: “I firmly believe that the district alone is without resources. We just don’t have it. So I would like to see a collaboration.” She said other districts could help Detroit train its teachers: “I think we have to do a better job in terms of exposing our teachers to better development.”

“Are they not coming with that knowledge already?” Lula Gardfrey asked.

“But I think that we can support them more,” Vaughn replied. “Our students have mental health issues. They have economic issues. Just what the teacher learned in school isn’t going to be enough when that child arrives at 8 a.m. in the morning.”

When the gong sounded again, Nita Redmond felt torn. She believed Vaughn had good intentions but was suspicious of any collaboration with charter schools.

The rise of charter schools, which enroll about one-third of the city’s 100,000 students, “should have never happened,” she said. “It seems like it has lowered the regular schools.” When another candidate, Shannon Smith, joined the table, Corley got to hear a different take on her question about the third-grade reading law.

“We need to communicate with parents,” Smith said. “There are a lot of parents that aren’t aware. Second, we need to work together with the administrators and the teachers on the curriculum, and figure out which curriculum would best support the students in reading.”

On the opposite side of the hall, another table asked Deborah Hunter-Harvill, the only incumbent in the race, about her plans for improving instruction in the district.

“Because nationally we’re at the bottom in reading and math, I start from the bottom,” she said. One of our policies is that parents attend parent training free to understand what their kids are being taught. All of our parents don’t come, but if you just get 40 in one classroom in one day, they go home and tell other parents.”

Theresa White had a seat right next to Hunter-Harvill, and she liked what she saw. “That has been a culprit, the lack of participation by parents,” she said.

In the next seat over, Rainelle Burton, who attended high school in Detroit and has lived in the city for decades, came to a different conclusion.

“I’m not hearing anything that says, ‘this is inventive and creative,’” she said.

The up-close-and-personal format didn’t make things easy for the candidates.

“It was definitely not comfortable,” Vaughn said, adding that she wished she’d had access to the pre-written questions beforehand.

But for voters in the room, the format made things easy. In a straw poll after the event, virtually everyone in attendance said they planned to vote.

“We were able to talk to them one-on-one, it’s not just looking on TV,” Nita Redmond said, adding that she came away with a good idea of who would get her vote (she declined to say who). “We were able to talk to them and evaluate ourselves if this would be the best person to lead my district.”

Surveying the room as the forum wound down, Michelle Broughton was of two minds. She carries with her four generations of experience with the district — she is a computer instructor at Renaissance High School, her father graduated from Chadsey High School, a Detroit Public School, in 1961, her children attended the district, and her grandson is in the eighth grade at McKinsey Elementary — and she said she’d heard a lot of what she called “pie-in-the-sky” ideas at the forum.

No one had offered a solution for the roughly 90 classrooms in the district that were without a teacher on the first day of school — a problem that had affected her family in the past.

“If my child goes to school every day and comes home and says, ‘Grandma, I don’t have a math teacher,’ that child is losing weeks,” she said.

But she said the event gave her a feel for the candidates — and reminded her how many Detroiters share her dream of a thriving school district.

“I’m here because I have hope,” she said. “I see a brighter future, and I hope that I pick somebody who will help.”