She’s scheduled office visits with her professor. She’s asked the teaching assistants for help. She’s dropped into the math learning centers.

But still, despite excelling in her other classes, Marqell McClendon has struggled in the low-level math class she’s taking during her first semester at Michigan State University.

“Sometimes when I’m in class and I’m learning, some things start to feel familiar from high school and I’m kind of like, ‘I learned this already but I don’t really understand it.’ And I don’t know why I don’t understand it because it looks familiar.”

So she’s finding help any way she can — watching educational videos online and, when the work seems impossible, approaching strangers in her dorm and asking them for help.

It’s an unfamiliar scene for McClendon, the valedictorian of her graduating class at Detroit’s Cody High School who’s used to students coming to her for help. Now, the tables are turned. She describes it as “bittersweet.”

Marqell is among a group of recent Detroit high school graduates Chalkbeat is following through their first year of college, for a series highlighting the complex dynamics that make it difficult for students from disadvantaged communities like Detroit to complete college.

The challenges students face — academic, financial, social — are why so many colleges have turned to programs that help ease the transition, from summer bridge programs that provide academic and social support during the summer between high school graduation and the beginning of college to similar programs that operate during the academic year.

The programs differ in structure, content, and length, but all reflect hope on the part of the colleges that giving first-generation students and underrepresented students extra support will pay off in terms of increased graduation rates.

Nationally, only 60% of students who enroll at four-year institutions earn a bachelor’s degree within six years. That is the average for all students — the six-year college graduation rate is much lower for black students (40%), Hispanic students (55%), and low-income students (49%).

Meanwhile, one study found that a third of students whose parents had no college experience dropped out after three years of school, compared to 26% of those whose parents had some college education and 14% of those whose parents had bachelor’s degrees. First-generation students are often at a disadvantage because their parents struggle to help them navigate college life.

Closer to home, nearly half of graduates from Detroit’s main district who make it to college must take remedial courses. For charter schools in the city, it ranges from 32% to 75%. Taking remedial classes comes with another set of challenges. It can be discouraging, particularly for students used to excelling in high school. But it can also be costly, given the students often are paying for classes that don’t count toward college graduation.

At MSU, McClendon is taking advantage of one such program that is geared toward students studying in the university’s College of Natural Science. Called the Charles Drew Science Scholars, it arms students – most of them from underrepresented communities – with intense academic advising, academic coaching, career advising, and a connection to a tight-knit community. At last count, 72% of the Drew students graduate from college in six years.

For McClendon, the Drew program has given her something she wouldn’t have gotten on her own: a small community of peers and adults she can turn to for help.

“They can actually cater to our individual needs,” McClendon said.

She may need it to get through her math class, which she must pass to get into the upper-level math she needs for her biomedical laboratory science major.

The first big test came when she took her midterm exam in mid-October. Walking out of the room that day, she wasn’t sure whether any of the work she’d put in would pay off in the final score.

This year, Chalkbeat reporters in Newark and Detroit are examining whether students from struggling schools are prepared for college — and whether colleges are prepared for them. Catch up on the Ready or Not series here.

***

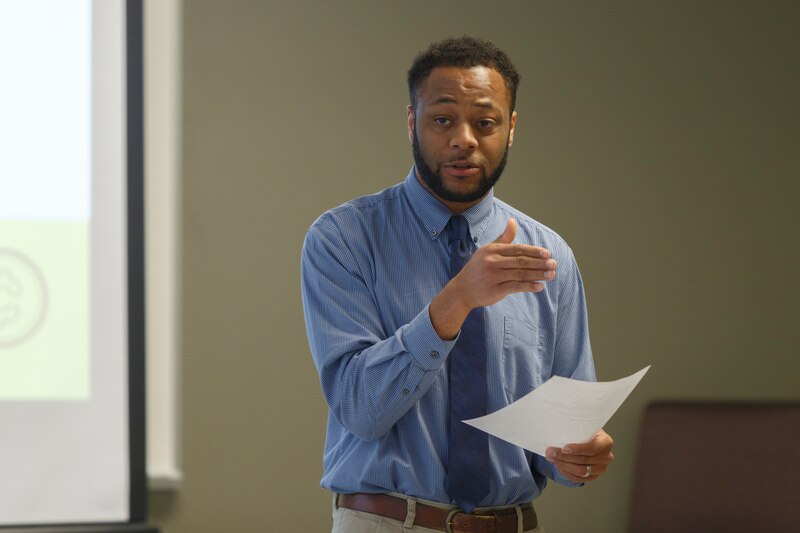

It was mid-afternoon on a drizzly Wednesday afternoon in Mount Pleasant, and inside Ronan Hall, the students in the first-year experience seminar class were peppering a couple of guest speakers with questions about loans and credit. But when the conversation turned too heavily toward credit cards, Marceil Davis interrupted.

“By and large, these are first-generation college students,” Davis, the teacher of the class, said from his seat in the back of the room, where he’d been observing while the guests spoke. “One of the worst things we can do, on top of loan debt, is to add credit card debt.”

It’s an important piece of advice, given that more than a third of college students report having credit card debt of $1,000 or more, according to a survey released earlier this year.

But in this class at Central Michigan University, the students are getting guidance from people like Davis, an academic advisor with a program at the university that is aimed at ensuring students like the ones in this class – either first-generation students or those from low-income families – can successfully navigate their freshman year.

“We’re Pathways,” Davis told the students. “We’re a little more up in your business. The reason we do this is to set you up for success.”

The Pathways to Academic Success program is funded by a state grant. Multiple other Michigan colleges run similar programs through the grant. At CMU, the program helps about 150 freshmen each year.

Demetrius Robinson, a recent graduate of the Jalen Rose Leadership Academy in Detroit, is one of them. He said being part of the program provides distinct advantages for students.

“You get that experience that a lot of other students miss out on,” said Robinson, whom everyone calls Meech. “They don’t have the academic support, the academic advisers that we have or the resources we have available to us. I can come in here any given day and go… to the Pathways office and sit and get any kind of help I need.”

Mary Henley, director of the Pathways program, said it has four goals: helping students increase their grade point averages, advance their academic standing each year, increase their acceptance into their major, and graduate.

“Those sound like very simple goals,” Henley said. “But we get students on campus, they get through high school and they do really well and they come to college and it’s a culture shock. We are there to help students like Meech navigate. He was a superstar in high school and you come to college and all of a sudden you’re starting over.”

Robinson, an extrovert, is already making a name for himself. He cuts hair and helps students with fitness training, something he’s been doing for years thanks to his family’s fitness business. He’s become involved in campus organizations, and recently became certified as a campus volunteer through Pathways, which will allow him to lead or assist with campus tours for prospective students, as well as participate in panel discussions for those touring the campus.

But like any first-year student, Robinson has faced challenges. He can cite times when he’s struggled to meet his professors’ expectations.

“I do what’s asked, but when I get my papers back, sometimes it’s like, ‘Dang, I thought I did everything,’” he said. “I’ve come to this realization that … I’m putting out my best work … but it isn’t enough.”

He’s dealt with it by talking to his instructors. He’s found them receptive to providing feedback. They’ve told him how he can improve his grades. Now, he said, he has a road map to finishing the semester with strong grades. He hopes to end up with mostly As and Bs, but said a C is possible.

That his professors have been willing to help is surprising to Robinson.

“These professors actually do care and they do try to help you. Not just me. They help all students in the class.”

Henley, the Pathways program director, understands the challenges her students are dealing with. She was one of them decades ago, when she arrived on the CMU campus as a freshman in 1979. She struggled not only as a black student coming from Flint to a predominantly white institution, but also as a first-generation student.

“I’m able to offer students who are coming here the way that I did a smoother path,” Henley said.

***

Lately, Kashia Perkins has been mulling a decision that could dramatically alter her future.

When she arrived as a freshman at Michigan State University in August, she was on a path toward a degree in human biology.

Now, she’s not so certain.

Her biggest concern? Whether an undergraduate degree will be enough to land her a good job.

“I definitely would need to go to medical school. I wasn’t sure if medical school was for me.”

Perkins raised the prospect of switching to MSU’s nursing program with Kai Brown on a recent afternoon. Brown, who like Perkins is from Detroit, is herself majoring in human biology and is planning to go to medical school to become a surgeon. She urged her younger classmate to think hard before making a big switch.

“I’ve been in that space where I considered nursing and not medical school as my route,” Brown said. “You have time to decide if that’s your idea of what you want to do with your life.”

The two became connected through a university program called Big Sister Little Sister, which pairs incoming freshmen with older students who can help guide them through their first year. Brown, who graduated from Detroit’s elite Cass Technical High School, is a senior at MSU.

For Kashia, it’s a reversal of roles. She’s used to being the big sister. The one setting the example. The one her younger siblings look up to.

Now, she’s the one looking up.

“I thought it would be nice to have somebody who has college experience who could mentor me,” Perkins said.

Brown wishes it was something she’d done as a freshman at MSU. She lived in the same building that held most of her classes, so she recalls feeling isolated — from the university as a whole, but also from the African-American community.

She and Perkins were only recently paired, so they’re still getting to know each other. Brown is mentoring two other freshmen. All three little sisters are majoring in science.

“It’s important to have a mentor, especially in college, and especially for someone who may be a first-generation student,” Brown said. “It’s not always easy trying to lead your own way. So, sometimes, you might need someone to lift you up when you need it.”

Perkins is involved in several other activities, including a dance team. She said being involved helps with time management, because the frequent responsibilities force her to keep track of the school work she needs to get done.

Like McClendon, her toughest class at MSU is a low-level math class. But Perkins reports doing well academically overall. She’s also enjoying being on her own for the first time.

“It’s helping me become more independent,” Perkins said.

And two weeks after that initial conversation with Brown about her major, things were starting to firm up for Kashia. She’s now decided to stick with the human biology major for now.

“This is what I’ve always wanted to do,” Perkins said. “I just have to work hard for it.”

***

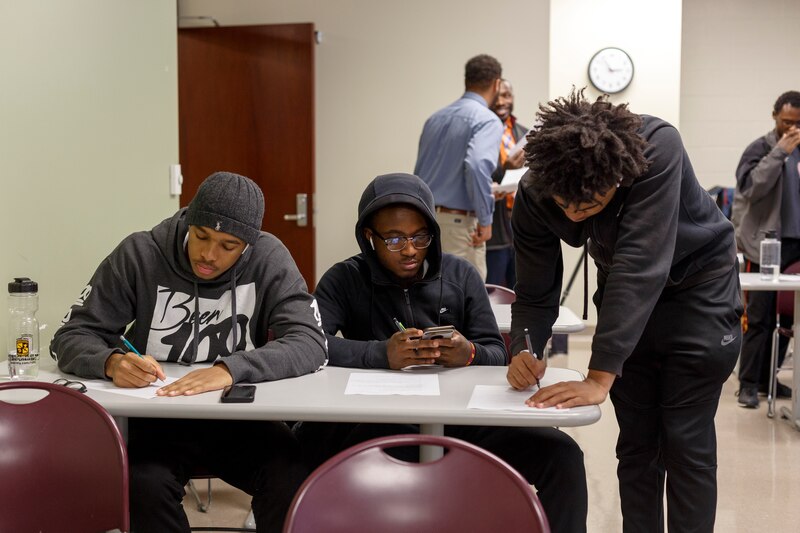

The Drew Scholars program at MSU began 40 years ago as part of an effort to increase the number of underrepresented students going into science fields. The program takes in about 75 students annually, with the main criteria being strong high school grade point averages and strong performance on the SAT and/or ACT, with particular attention paid to math scores.

Well over 90% of the students involved in the program return for their second year at MSU, officials say. While similar programs also report positive results, it’s hard to make sweeping statements about the effectiveness of such efforts at colleges and universities because they all take different approaches.

Jerry Caldwell, the director of the program, said math is emphasized because all of the degree programs in the College of Natural Science require at least a semester of calculus. Drew students are required to live in Rather Hall during their freshman year, with nearly all living on the same floor as the program offices.

The residential piece is a crucial part of Drew Scholars, Caldwell said. The goal, he said, is for students to become part of a community and to feel connected to students with similar academic interests.

“This is a place where students can get lost,” Caldwell said, referring to the large campus that enrolls nearly 40,000 students. “It’s very important that they have a connection to something or somebody. We’re here to help them navigate that environment.”

McClendon already has benefited from a key part of the program: a requirement that students meet with an academic adviser three times each semester during their first year. During her first session, McClendon confirmed her suspicions that it would take her five years, not four, to earn her degree.

“It made me realize it’s a lot of work I have to put in,” McClendon said. “But it kind of got me mentally prepared for what I should expect.”

Students also must take a seminar class during their freshman and sophomore years, taught by Caldwell. Among the key principles of the first-year class: professionalism, connecting with faculty, time management, the teaching and learning process, community connections, and health and wellness.

Students are assigned an older student as a mentor, and there are a number of activities that bring alums of the program as well as professionals to campus to share their experiences. That’s how McClendon connected with a woman, a physicist, she hopes can be a professional mentor.

“It’s important to get those connections early because I may run into someone that can actually give me, like, a glimpse of what I think I want to do in the future,” McClendon said.

She learned how beneficial the program could be by listening to Antoine Douglas, who the last two years was a college adviser at Cody and is now working toward a master’s degree at MSU. Douglas helped her get into the program, and on the day she moved into Rather in August, he looked back at how it influenced him, a first-generation student who came to college knowing little.

“I was that kid that moved in that day, six years ago, and I was like, ‘What the heck?’” Douglas recalled. “The Drew program got me together. It shows you how to be successful. I can sing their praises all the time, because they got me through.”

With experience from the program to draw upon, McClendon is learning to advocate for herself. That’s how she ended up approaching strangers for help with that difficult math class. One night in particular, she was at a point where she thought she was in danger of failing. She figured, “I don’t have anything to lose.”

So she walked up to a young man who was studying in the common area of her dorm. And she asked him to help.

“He actually sat there for about an hour and a half and he helped me do my math homework and he helped me study for a quiz,” McClendon said. “He even told me that if I ever need help, I can just come knock on his door. It’s just nice that you can just run into people that are so willing to help you.”

Later, when she took her midterm exam, McClendon earned a B. But that’s still not good enough for someone who in high school was used to earning all A’s.

“That mindset kind of makes things better for me. It just makes me work a little bit harder.”

This story is part of a partnership with Detroit Public Television. It was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.