It was announced with great fanfare in 2016: The expansion of a college scholarship program for Detroit students to include free tuition at four-year colleges in the state — a step the city’s mayor hailed at the time as a way to remove barriers for young people.

But in the three years since, only a small number of students have met the academic requirements to qualify for the four-year scholarships that are part of the Detroit Promise — leaving scholarships going unused and money on the table.

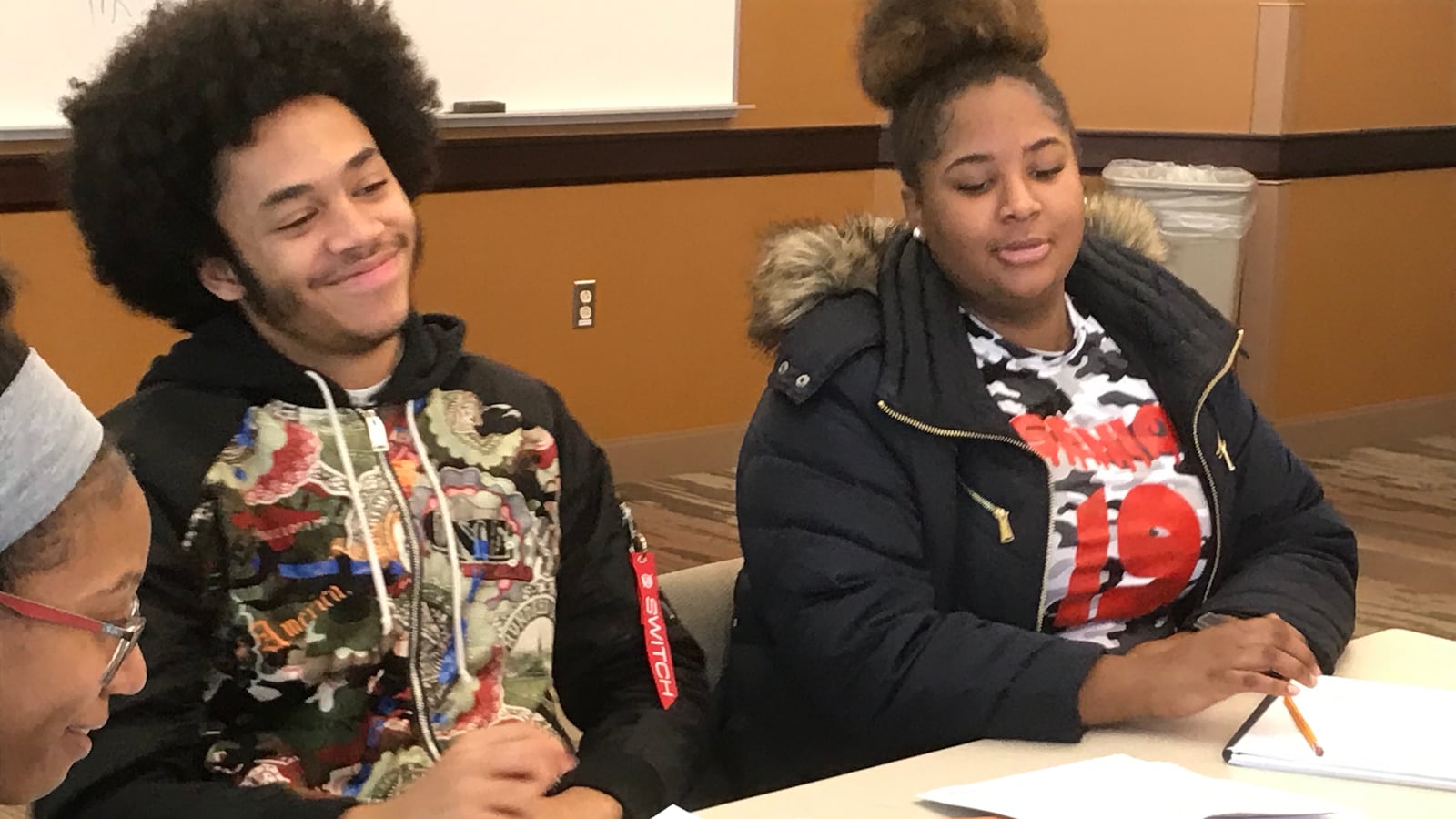

That’s why students like Myles Reed, Stephon Horton and others are giving up a chunk of their Saturdays for 12 weeks — traveling to the city’s downtown and sitting through a new three-hour class called Score Your Four that they hope will give them the boost they need to earn the scholarship.

“I’m just trying to get out of the house and go to college, for free,” said Myles, a senior at Henry Ford Academy: School for Creative Studies. “I don’t want to have my mom pay for college, or to put myself in debt for the rest of my life. ”

On a recent Saturday, the class began with a stern warning from the teacher about the importance of carving out time for homework. Every bit of it that’s assigned, she told the group of Detroit high school students, is directly linked to a skill they’ll need to master in order to beat the SAT.

“If you’re not doing the practice, you’re not going to see the results,” Katharine Buckley warned.

This first-of-its-kind class — created through a partnership between the Detroit College Access Network and EnACT Your Future — is unique because it was created with students like Myles in mind: Those who’ve already taken the SAT or the practice test for the exam and earned scores that don’t meet the guidelines for the Detroit Promise scholarship, but are close enough that the class can get them over the hump.

The Detroit Promise data show just a small fraction of the roughly 4,500 students who graduate each year from high school — including charter, traditional public, private, and home schools — meet the academic requirements needed to qualify for the four-year Detroit Promise scholarship. The requirements: a 3.0 grade point average and a 1060 on the SAT (or a 21 on the ACT).

This class aims to help more students get the cash. There’s a lot at stake, given the scholarship helps cover tuition and fees at 18 colleges and universities in Michigan — including the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, and Wayne State University.

Meanwhile, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer has made it a priority to increase the number of Michigan residents with some kind of postsecondary education.

“I signed up for this class because a lot of people in my family didn’t look at this kind of stuff, the SAT, as kind of important,” said Keshaun Hudson, a junior at University Preparatory Academy High School who dreams of becoming a pediatric anesthesiologist. “So, I feel like this will help me, as far as getting my test scores up.”

Two classes, which take place at Grand Valley State University’s downtown Detroit campus, launched for the first time in mid-January. Organizers plan to offer a summer version as well.

“The return on investment is crazy,” said Ashley Johnson, executive director of the college access network, which works to build a college-going culture in the city. Students invest their time, and if they’re successful, “there’s money waiting for them.”

EnACT Your Future developed the curriculum. The Detroit-based organization was created in 2014 to provide SAT prep classes at low-income high schools and community organizations.

“This test was the single barrier to my students being able to access college or the financial aid to make college accessible,” said Justine Sheu, the organization’s founder and executive director, who had previously taught in the Detroit school district. “I thought it was very unjust.”

The Score Your Four class is similar to the other classes EnACT teaches. The biggest difference: The students in the regular classes tend to be far behind academically, while the students in this new class have scores that are only about 80 to 100 points off the threshold for the scholarship.

The Detroit Promise is administered by the Detroit Regional Chamber. In addition to the four-year scholarship, there is also one that covers tuition and fees at community colleges. The latter has been around since 2013. Both are available to students who graduate from a Detroit high school. Both also are last-dollar funding programs, meaning aid from federal Pell grants and the state Tuition Incentive Program are applied first. The community college scholarship has no academic requirements.

Greg Handel, vice president of education and talent at the chamber, said that an average of 250 students each year qualify for the four-year scholarship. That doesn’t take into account the students who leave the state to attend school, or who attend a four-year school that isn’t a Promise partner.

“We definitely want to see the numbers increase,” Handel said. “Every year, if we could get another 10 to 20 more qualified and keep growing that number, we’ll start to make a dent.”

He’s encouraged by the creation of the class, and by the commitment of Detroit Superintendent Nikolai Vitti to increase the number of students who meet college readiness standards. Improving the numbers will be part of the evaluation goals for the superintendent and principals, Vitti said.

“It is an issue the district is focused on,” Vitti said. “We are aligning our work and outcomes to the Detroit Promise.”

The district has also created SAT classes in all high schools at the 10th and 11th-grade levels, expanded college visits, increased opportunities for students to earn college credit while in high school, and put college advisors in high schools, Vitti said.

A large part of the Score Your Four class is about academic skill building and learning content. The rest is about increasing students’ knowledge of strategies they can use while taking the test. During a recent class, Buckley on several occasions noted ways the SAT can trick students.

“She gives us help on what to do and what not to do,” said Diamond Arrington, a junior at University Preparatory Academy High School.

And the classes are interactive to keep students engaged by breaking them into competing teams to answer questions correctly.

Among the strategies: A method called “yay, may or nay” teaches them to be choosy, by identifying the “yay” questions they’ll answer right away, the “may” questions they might answer, and the “nay” questions they don’t know the answers to. This allows them to spend more time on the “yay” questions, and less time on questions they don’t know.

“She said, anything that’s difficult or challenging, just don’t do it because you want to be more accurate on the stuff … that you know you’re going to get right,” Keshaun said.

But that doesn’t mean they should leave those “nay” questions blank. The students are taught to answer every question, regardless. And there’s even a strategy to guessing. Instead of randomly choosing A, B, C, or D to answer multiple-choice questions, students should choose just one of those options. That could mean using the letter A for all of their “guess” questions. The argument: EnACT say there’s an even distribution of those answer choices, so students have a 25% shot at getting the guess answers right if they stick to one letter.

The students are taught process of elimination strategies to help them weed out incorrect choices. They’re also taught chunking — the process of reading chunks of passages, then answering some questions, then going back and reading another chunk. This is opposed to reading an entire passage at once, then trying to answer all of the questions related to it.

Reading the entire passage first is how Stephon Horton always approached exams. But he said it wasn’t effective. “I would forget stuff,” said Stephon, a senior at Southeastern High School. Chunking “helps me get stuff out of the way quicker, more efficiently.”

The students learn how to break down SAT questions to get to the bottom of what they’re being asked. During a recent class, Buckley had them read a passage in which the author wrote: “Others have accepted the ethical critique and embraced corporate social responsibility.”

Buckley walked through what could be some common traps. They talked about the more well-known meaning of the word “embraced,” and how it differs from the way it’s used in the passage. Buckley also displayed the question, “As used in line 6, “embraced,” most nearly means,” with these as possible choices: A) lovingly held, B) readily adopted, C) eagerly hugged, and D) reluctantly used.

“What did you eliminate right off the bat?” she asked.

One girl said she got rid of A. “Because with lovingly, you think of something that’s close to your heart.” The correct answer is B.

Students interviewed say they don’t mind giving up three hours of their Saturdays to take the class. They say the class has made them feel more confident and less stressed about taking the SAT. For Stephon, it’s also keeping options open. He still hasn’t decided what his plans are after high school graduation.

“I don’t know whether I want to go to college,” he said. “But this will help me.”