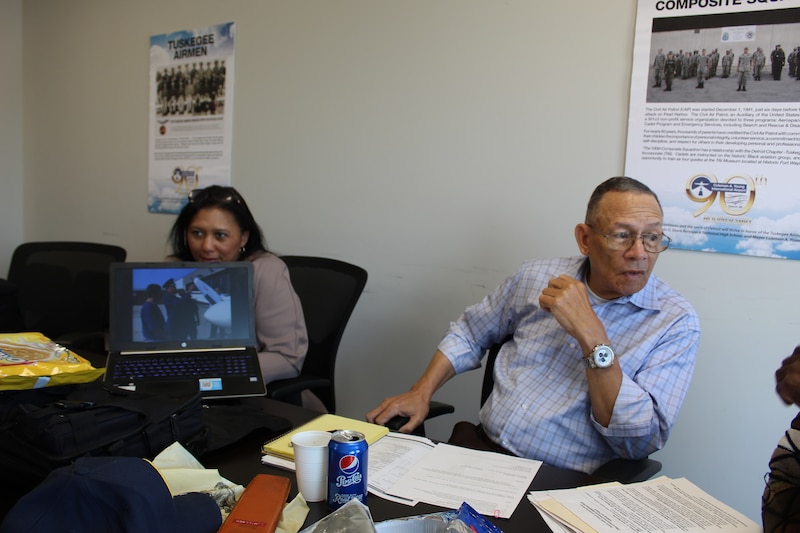

The time is 1350 hours. The meeting is running late, but Ret. Col. Lawrence A. Millben doesn’t run an air base any more, and he’s left military punctuality behind.

Besides, after nearly seven years of fighting, victory is in sight for the Davis Aerospace Technical Advisory Committee.

Millben and other activists have been pushing to bring Davis Aerospace Technical Academy back to the old Detroit City Airport since 2013, when the school was moved to a culinary school campus by a state-appointed emergency manager.

In August, the city board of education agreed to bus a small group of students to the airport for afternoon classes, calling it the first step toward moving the entire school back to the airstrip. Millben and other backers of the school claimed a victory — at least a partial one.

“The school was going to go away, but we raised so much purgatory that they didn’t have a choice,” he said. “We wouldn’t go away.”

Before it was moved away from the airport, Davis Aerospace Academy was one of the only high schools in the country that trained aviation mechanics. Millben, the first black graduate of the school, believes that his education there propelled him through a high-flying military career.

By refusing to let the school die, he and other activists scored a win after two decades of unparalleled loss for the Detroit district. Their efforts suggest that a profound disconnect between Detroiters and their schools is beginning to mend.

When Roy Roberts, a state-appointed emergency manager, announced plans to move the school, saying it would save the district $1.5 million, Millben understood immediately that the decision was effectively a death sentence.

Millben, 82, graduated from Davis Aerospace in 1954, when it was still called Aero Mechanics High School. He wears a neat mustache and bifocals, and would spend more time tinkering in his professional-grade electronics lab if he didn’t spend so much time at public meetings. He holds two U.S. patents for innovations in electronic circuits, and does not use email or text messages.

As Millben rose through the military ranks, he stayed involved with the school, helping to rewrite the curriculum and rename the school after Benjamin O. Davis, the first black general in the U.S. Air Force. Millben was himself the first black man to hold numerous military leadership positions. He believes his time at Davis Aerospace helped him succeed despite the racial discrimination he encountered along the way.

But in 2013, it seemed unlikely that Detroit students would get the same opportunity. Without access to the airport, the school could no longer give help students obtain the federal certification in aviation mechanics that would give them an inside track to steady, high-paying jobs.

The district tried to solve the problem by moving an airplane along with the school. Crews disassembled a Cessna 150, packed the parts in boxes, and shipped them to Golightly Career and Technical Academy, which also houses a culinary arts high school.

The parts were dumped on the floor in disarray. The plane is still in pieces.

In any case, the students couldn’t use it because Golightly is in a residential neighborhood, where the noise produced by a plane engine would violate city rules.

Millben objected in public meetings, but it was no use. Two years earlier, former Gov. Rick Snyder had signed legislation expanding the state’s emergency management law, giving Roberts virtually unilateral power.

“I knew we were going to fight, but I didn’t know how to fight,” Millben recalled. “I didn’t have money for lawyers and I didn’t have the district behind me. So I decided to hit them with our expertise.”

The plan was to outlast the emergency managers. All Millben and other activists had to do was talk loudly enough to keep Davis Aerospace on the front burner while they waited for someone more sympathetic to come to power.

This was slow, full-time work. Supporters of the school met every week over Oreos and Diet Cokes to rehearse their arguments and coordinate schedules. They sometimes attended public meetings six days a week to make their case.

Members of the committee were acting as “border crossers,” a term used by Camille Wilson, an education professor at the University of Michigan, to describe activists who bring community demands to the attention of policymakers.

“It’s important for the public and policymakers and officials to keep in perspective that this is actually healthy,” she said.

District officials say the Davis Aerospace story is one sign that the district is once again willing to listen to community concerns.

“Working with the community on projects like [Davis Aerospace] is all about moving away from a district vs. activist attitude,” board member Misha Stallworth said. “We have to be able to listen to one another and work together to develop sound programming.”

In a city known for its community organizing, advocates at Davis Aerospace proved especially adept at catching the public’s eye.

Someone in California read a news article about Millben being barred from a public meeting. Millben was quoted as saying it took 70 years for him to be kicked out of school.

In 2017, the Californian, who Millben won’t name, put a $1 million check in the mail to support the group’s efforts.

They put the money into the airport, using it to renovate a building next to the old airline terminal. This became the new headquarters of the Davis Aerospace Technical Advisory Committee, which had continued to meet despite attempts by school officials to disband it.

But their long-term goal still seemed out of reach. Three emergency managers and several school principals came and went, and no one seemed willing or able to move the school back to the airport.

“Every time we thought we saw a light at the end of the tunnel, it turns out it was an oncoming train,” Millben said.

But in 2017, when a locally elected school board took control of the district for the first time in nearly a decade, activists thought they finally had a real chance. The new superintendent, Nikolai Vitti, was receptive to the idea of moving the school back to the airport.

“In the first meeting, I said, ‘This makes sense,’ ” Vitti recalled recently. “I said I would do it. I just needed time and resources.”

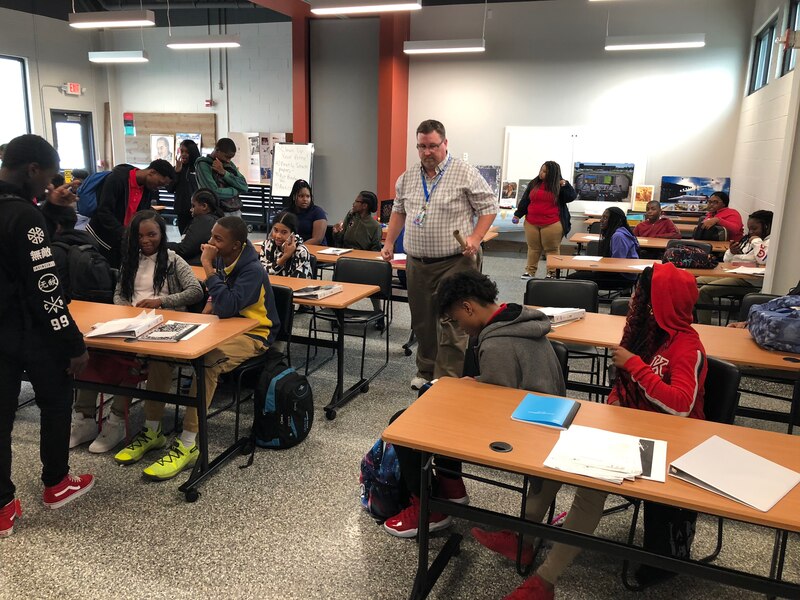

On the first day of school two years later, an estimated 50 ninth-graders were bused to the airport, where they took aviation classes in new classroom spaces built with the $1 million donation.

Everyone celebrated the move, but the school is still a far cry from what it once was. The instructors, hangar, and airplanes that the school would need to again offer students an aviation mechanics certification won’t come cheap. Millben guessed that adding a hanger and expanding the building to accommodate four grades could cost $20 or $30 million.

He doesn’t expect the district to put up that kind of money, not when it faces a $500 million bill to repair its existing buildings.

But advocates of the school insist that the end goal should be training mechanics.

“There are companies that will start an FAA-licensed mechanic at $60,000 or $70,000 a year,” Millben said. “That’s what the city needs. People who make real money.”

The district acknowledged this reasoning, noting that the aviation industry will face a shortage of 10,000 mechanics within a decade, according to a recent study by the University of North Dakota.

Both the district and activists hope philanthropies will help shoulder some of the cost.

In the meantime, plans for the school’s future are still being ironed out. To start out, students could work toward federal certification in aviation electronics, which can be offered more cheaply than mechanical training. The school also advertises itself as a pathway to a pilot’s license, although students would need many additional hours of expensive flight training after high school to get jobs as commercial pilots.

In the first two weeks of school, instruction at the school focused on general aviation concepts. On Monday, the students learned about the force that helps rockets lift off by attaching as many paper clips as possible to balloons and launching them to the ceiling.

Millben hopes the students will begin learning the nuts and bolts of repairing airplanes before long. But he said it’s a “giant step” that students like Jeramiah Simpson, 14, are studying at the airport at all.

“I’m a hands on person,” Simpson said. “If we were just in the classroom learning about history, it wouldn’t be the same.”

The scene had a celebratory air, but Beverly Kindle-Walker, a former city airport commissioner and advocate for Davis Aerospace, said she’s not prepared to declare victory.

“Oh, this is just the beginning,” she said.