King Bethel jumps at chances to perform, even if the stage is a laptop.

When his fifth-hour voice class started around 12:30 p.m., the teacher asked the class to load their Flipgrid music software and sing a do-re-mi scale. King’s eyes lit up. His back straightened. He snapped his fingers and tapped his foot to the piano sounds, focused on matching the rhythm.

Meanwhile, chaos accompanied King’s solo act. Students peppered the teacher with questions about navigating online learning tools, activating accounts, and submitting homework.

King didn’t mute the background noise. He welcomed the challenge of working through distractions. He imagined singing in front of a crowd, and he wanted to keep his cool.

The teacher paused, then sighed. “Most of your questions,” she said, “have already been answered.”

The coronavirus pandemic has upended public education and forced students across the country to learn behind computer screens. In Detroit, the school year got off to a rocky start marked by technical glitches and student complaints about packed schedules. For new high schoolers like King, finding a sense of normalcy — and a place to belong — will be hard.

King’s older brothers told him ninth grade would be a game-changing year, a time to grow up and get serious about his passions. At 14, King is committed to the arts. He’s also used to being noticed and appreciated in a typical school setting, pre-coronavirus. What if he can’t find an ally on the school staff to support him? What happens if he doesn’t shine over a screen?

Since the start of virtual classes at Detroit School of Arts, a district high school focused on arts preparatory training and college readiness, King has only sung once during school and it was brief. The day he sang the do-re-mi scale, King didn’t know when the class would sing together again.

Still, he had practiced the day before, singing the song, “Together We Stand” by The Winans more than 10 times in his bedroom, watching his posture and breathing in a mirror.

Learning the song was one of his first vocal assignments. Before the pandemic, he’d sing as his teacher played the piano. An off note would be corrected together in real time. Now he has to record the song and submit an audio file, then wait for a critique.

There have been moments while practicing that doubt has crept in: “If you practice the wrong way, how is it good practice?” King said.

King has always had a champion in his mother, Netha Johnson. When King was 2, she bought him a Fisher-Price toy keyboard. She enrolled him in poetry workshops, entered him in local singing competitions, drove him across the city for performances, and paid for professional headshots. She takes videos of his performances and helps share them on social media.

All of that energy and optimism was sapped by COVID-19. In March, Johnson tested positive for the virus and battled through it at home for almost 40 days, bedridden for many of them.

“It was the worst time in my life,” she said.

Detroit was an early COVID-19 hot spot. Thousands of Detroiters fell prey to the virus, many spending weeks clinging to life on hospital ventilators. By the end of March, the city had more than 2,000 positive cases and the death toll had reached 75. The city mourned the painful scale of the losses — from union leaders and teachers to a janitor and a politician — and the threat of the virus robbed families of chances to grieve at funerals.

King remembered his mother turning white on the hardest days of her illness. It’s hard for him to talk about it, even now.

“The whole time I was scared of losing my mom,” he said. “I prayed about it, talked about it, and kept my hopes up.”

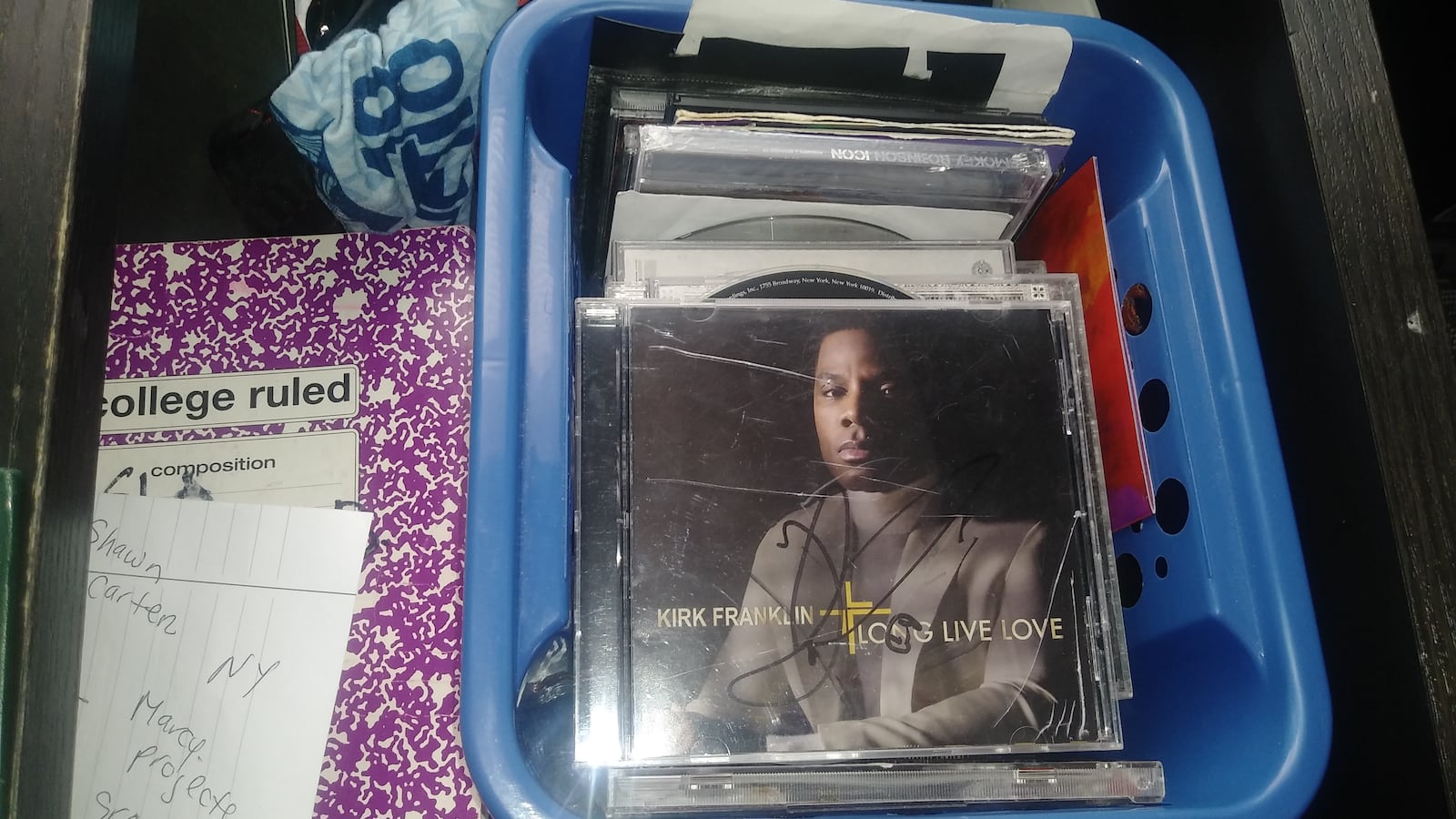

King’s bedroom on Detroit’s east side reflects his love of music. Within those walls are a full-size keyboard, karaoke machine with a microphone, a case of old jazz and blues CDs he inherited from his grandfather, and a signed CD from gospel artist Kirk Franklin.

“He has the drive of an adult, not a kid,” said Angela Kee, the choir director at Detroit Academy of Arts and Sciences, where King attended middle school. “He was the kid where you give an assignment to an entire group, but he’s the one who comes back the next day with it completely mastered. He was the Michael Jordan of DAAS choir. Just give him the ball.”

Shifting musical arts training online is complicated. It’s harder to assess a student’s vocal delivery, pitch, and tone listening to an electronic file, Kee said. During past rehearsals, students would sing with Kee beside them. She would point out mistakes, and they could correct themselves in the moment. Now, she’s critiquing recordings without them present.

At DSA, King’s new school, principal Mayowa Lisa Reynolds said the high school is emphasizing individualized vocal training and more in-depth lessons on musical genres, theory, and history. Ninth grade will be the year to build foundational skills.

“There is such a variety of work and learning that can happen in the arts that just performing won’t get you,” she said. “We don’t want to just be a performing arts school but prepare them for college and life. This pandemic part gives us time to dig deeper with that.”

But Reynolds has had to comfort many students’ disappointments about not having in-person band, choir or theater practices right now. She reminds them that being apart is only temporary.

“I let them know that schools are people,” she said. “This building can’t come alive without them. But in order for us to get to that, we have to stay safe. Right now we’re gonna build on a strong foundation and we will get together” one day.

Kee was his champion at his old school. Johnson is his champion at home. It’s unclear this early on whether King will find one at his new school.

“I would hate for him to get discouraged because this is all he knows,” Kee said.

King feels safer learning at home right now, but he misses the magic of his middle school choir. It makes him a little sad.

“Whenever I practiced with my school choir, we used to always listen to each other — the altos, tenors, sopranos,” he said. “Whenever we sang a song, we learned the lyrics and the harmonies at the same time. We benefited off each other instead of...singing it by yourself. Now, you have to learn everything on your own without people helping you along the way.”

The day of King’s voice class was the 10th day of school for thousands of students in the Detroit Public Schools Community District. After a summer of uncertainty and fierce debate about what the 2020-21 school year should look like, the district returned for fall offering both in-person and remote instruction. About 75% of district students are learning online. King’s arts school opted to begin the year 100% remote, though about 40 students are taking their online classes in a learning center inside the school, with staff supervision, just like at other district schools.

King attended his voice class in the backyard, to enjoy some fresh air and sunlight.

His house stands next to a lumber company on Seven Mile and Hawthorne, close to the freeway, so the sounds of buzzing machinery competed with the buzzes of bees hovering over his head.

Once the tide of troubleshooting questions from King’s classmates subsided, the teacher shifted to a lesson on African-American spirituals, religious songs that describe the pain of slavery and focus on themes of freedom from oppression.

Each student shared thoughts on the songs’ deeper meanings. King chimed in with his own interpretation of “Wade in the Water” and how the song mapped out the ways people could escape.

King thought about the teacher’s next question: “Why do you think it’s important for us as African Americans to sing Negro spirituals?” she asked.

She gave the students a few seconds to pause and ponder the concept. Then, she shared a video link in the Microsoft Teams chat. While watching the video, King learned about the powerful simplicity of spiritual music. Many songs were composed using just five notes on the do-re-mi scale, which King had practiced moments earlier.

“Besides our freedom...what else was taken?” the teacher asked, referring to the legacy of slavery.

“Shelter!” one student said.

“Language!” King said.

“There is one thing that was taken from us that we cannot get back,” the teacher said. “That is the connection to our past.”

These spirituals are “one of the last surviving histories we have of what our life was like if we had stayed in Africa,” she said.

The lesson resonated with King. He took part in his middle school’s peace march over the summer, fighting for racial justice in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. He writes his own songs, which embrace themes of empowerment and resilience. This has been a tough year for the 14 year old.

Another school day ends without singing a full song — just those do-re-mi notes — but the class quenched his thirst for knowledge.

Going into high school, King looked forward to showcasing his talent and performing for his peers and teachers. The reality of learning the arts virtually is slowly hitting King. Still, he’s charging ahead.

“I want people to know who I am,” King said. “I want them to know I will accept any challenge. I’m not just a ninth grader.”