The Troy School District in suburban Detroit shut down its in-person classrooms last week because of an alarming rise in COVID-19 cases. Just like that, life for the Onyx family was back to impossible.

Stephanie Onyx sees herself as a single mother and an accountant — not a teacher. She never doubted that she needed help to support her two children, both of whom have severe, complex special needs.

Both of her children are accompanied by aides every minute of a normal school day. Their personalized education plans call for a litany of therapies — speech, occupational, physical. Her son, a high school freshman who is unable to walk on his own or speak due to a chromosome disorder, built up strength at school with help from a special “stander” machine.

All that help disappeared when Troy classrooms shut down in March. The district allowed some students with special needs to return to school campuses this fall, but that plan was canceled after a month and a half of in-person instruction. Onyx will once more spend all day trying to keep her children interested in online lessons and sneaking in a few hours of work when they are watching TV or in bed.

When the Troy school board decided last week to revert to online learning, “It was like, ‘Oh my God, how am I going to do this again?’” Onyx said. “I barely made it through March to June.”

Six months into the pandemic, it is clear that in-person instruction is indispensable for a significant number of students. Think of restless elementary schoolers, students with special needs, English learners, and students who lack reliable access to devices and Wi-Fi. Yet many of these students are being shut out of their classrooms as a new wave of coronavirus infections pushes more districts to return to online learning.

As infection rates rise sharply in Michigan and hospitals sound the alarm about dwindling emergency room capacity, state officials have called on schools to prioritize their most vulnerable students as they plan for the next phase of the pandemic.

In-person learning “is especially important for … our severe special needs children, our beginning English language learners, our fledgling readers,” State Superintendent Michael Rice said this week. “At a minimum, they should have an opportunity to learn in school.”

But while some districts are heeding Rice’s words and allowing high-need students to learn at school, a growing number of district leaders say it’s now too dangerous to keep classrooms open for anyone.

“There are few easy answers during the pandemic,” said Kerry Birmingham, a spokeswoman for the Troy district. “These decisions, while difficult, are made with a specific focus on health and safety while continuing to make every effort possible to continue educating our students in the midst of a global health crisis.”

Onyx has filed several complaints against the district since May, she said, asking it to pay for the services that her children would normally receive at school. The case is pending. Birmingham declined to comment on the circumstances of any particular students.

A rapidly growing list of districts are shutting their classrooms completely in response to grim COVID-19 figures. Two weeks ago, roughly half of Michigan’s counties were given a COVID-19 risk grade of “E”, the worst possible rating. By Tuesday, as new cases skyrocketed, virtually every county in the state had an “E” grade. The Detroit Public Schools Community District — the state’s largest district — announced Thursday that it would end in-person learning until January at least. Officials there had fought for months to offer some in-person instruction to families that needed it. On Sunday, Gov. Gretchen Whitmer announced that beginning Wednesday, all high schools in the state would need to shut down face-to-face classes and transition to virtual learning.

Across the state, districts that had been offering some in-person instruction closed their classrooms. Others, like the Royal Oak district in suburban Detroit, canceled reopening plans.

Plenty of families and teachers backed the move to online instruction as a necessary safety measure, even if they recognized that it would be hard on students.

“I supported the plan to go back to [in-person instruction] when the county was at a C” risk level, said John Staniszewski, whose two children attend Keller Elementary in Royal Oak, where Staniszewski is a member of the PTA. “Then of course I supported them when they pulled the plug.”

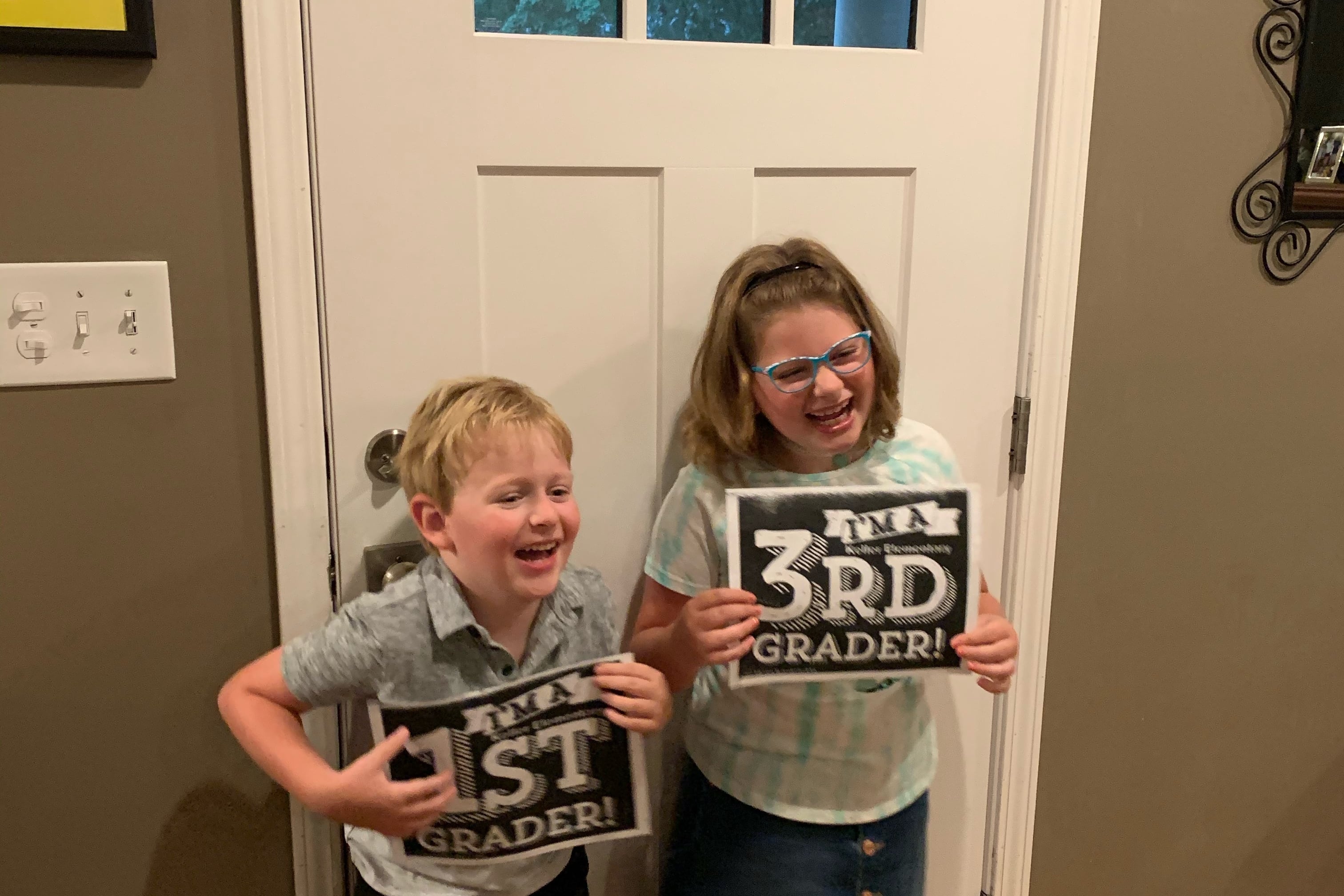

Staniszewski considers himself lucky: Both he and his wife are able to work from home, and they’ve been able to help their children learn online. Still, he said the district’s decision was a blow. After eight months of remote learning, “everybody needs some personal space,” he said. His children, for their part, had been looking forward to seeing their friends and to wearing their new backpacks.

Just days before the first day of in-person school, the Royal Oak school board voted to stick with virtual learning.

Mary Beth Fitzpatrick, Royal Oak superintendent, said in an email that the district had no good options as cases rose.

“Face-to-face instruction is preferred, and so making decisions to implement plans that fall short of that goal are difficult to make,” she said. But she said the state has indicated that schools should close completely when COVID-19 metrics reached current levels.

Students with disabilities in Royal Oak had been receiving some services in-person, even as other students learned online, but that ended this week.

One parent told the Royal Oak school board at an emergency meeting last week that virtual learning “just really isn’t an option” for her son, who is on the autism spectrum.

Online instruction “is not going to work with him whatsoever and on top of that I have to deal with a [general education] student who is in kindergarten,” she said, adding that her son with special needs has “regressed very significantly” since March.

Families and their children will pay a heavy price for the spike in new cases and the resulting school closures, said Sarah Reckhow, a professor of public policy at Michigan State University. Still, she said faulting districts for closing classrooms is difficult as the number of daily COVID-19 deaths in Michigan reaches its highest mark since May.

“For some districts it was a mistake to not open in August, but I don’t think it’s a mistake to be closing right now,” she said. The COVID-19 numbers are “simply awful, and obviously it’s a failure of leadership at every level.”

Reckhow felt the consequences personally. This spring, her first-grade son “didn’t engage online in any really meaningful way,” she said. When his school district returned to virtual instruction in the fall, she enrolled him in a private Catholic school that kept its classrooms open.

That only lasted three months — the Catholic school recently announced that it was going virtual, too. Reckhow agreed with the closure decision given rising case numbers, but says the in-person classroom time paid off for her son.

“In 12 weeks of in-person first grade, he learned how to read,” she said.

She acknowledged that not everyone has the privilege to send their children to private school, particularly in Michigan’s most vulnerable communities.

“The idea that you reopen the economy in some form and that schools are an afterthought is such an utterly irresponsible proposition that was particularly insensitive to the needs of working families, lower-income families, and the roles of women as both caregivers and members of the workforce,” she said. Indeed, women have left the workforce in droves during the pandemic.

Stephanie Onyx doesn’t have the option of leaving her job because she is the family breadwinner. When she learned that Troy was canceling in-person classes for all students, she furiously fired off emails to the district, asking again if they would give her children the services they normally received at school. Until then, the family is shifting back to a routine that never really worked.

Onyx spends much of her day trying to keep her children focused on their virtual lessons. Both are working with a dedicated aide online, but Onyx worries that they are still regressing, and some of the services they normally receive, such as physical therapy, can’t be easily replicated online. Her daughter gets bored and wanders away from the screen. Her son, who relies heavily on routine, sometimes expresses his frustration by biting himself.

“There were no cases reported in their classrooms,” Onyx said. “Knowing what the kids are losing by not being in the classroom, to me, moving them to online learning is just ethically wrong.”